Bloody Times (10 page)

Authors: James L. Swanson

While the three ministers spoke for almost two hours, more than a hundred thousand people waited outside the White House. In the driveway, six white horses were harnessed to the magnificent hearse that would carry Lincoln’s body. Nearby more than fifty thousand marchers and riders were waiting in line. Another fifty thousand spectators lined Pennsylvania Avenue. Most wore symbols of mourning: black badges containing small photographs of Lincoln, white silk ribbons bordered in black with his picture, small American flags with statements of grief printed in black letters over the stripes, or just simple strips of black crepe wrapped around coat sleeves.

The night before there was not a vacant hotel room in all of Washington, and many people from out of town slept along the streets or in public parks. Some mourners had arrived near the White House as early as sunrise to stake out the best viewing positions. By 10:00

A.M.

there were no more places left to stand on Pennsylvania Avenue. Faces filled every window, and children and young men climbed lampposts and trees for a better view. By the time the funeral services ended and the procession to the Capitol got under way, they had already been waiting for hours.

It was a beautiful day. At 2:00

P.M.

soldiers in the East Room surrounded the coffin, lifted it from the platform, and carried Abraham Lincoln out of the White House for the last time. They placed the president in the hearse.

Cannon fire announced the start of the procession; guns boomed. Every church and firehouse bell in Washington tolled. Witnesses remembered the sound of the day as much as the sight of it. Tad Lincoln joined the procession, and he and his brother Robert rode in a carriage behind the hearse. The procession was huge. Among the marchers were members of the army, navy, and Marine Corps, and judges, diplomats, and doctors. One group of marchers suggested the cost of the war: wounded and bandaged veterans, many missing arms or legs, many on crutches.

The hearse that carried Lincoln’s body down Pennsylvania Avenue.

When the procession reached the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, soldiers carried the flag-draped coffin up the steps of the Capitol. The crowds watched in silence as the soldiers carried the coffin inside and laid it upon a platform. It was left under the dome with a guard of soldiers keeping watch over the dead president.

When Jefferson Davis rode into Charlotte, the people there were not happy to see him. Only one man would allow the president of the Confederate States of America to set foot in his home. An officer explained why to Burton Harrison: “The major then took me aside and explained that, though quarters could be found for the rest of us, he had as yet been able to find only one person willing to receive Mr. Davis, saying that people generally were afraid that whoever would entertain him would have his house burned by the enemy.”

Not long after his arrival in Charlotte, Davis gave a speech to an audience that included a number of Confederate soldiers:

“My friends, I thank you for this evidence of your affection. If I had come as the bearer of glad tidings, if I had come to announce success at the head of a triumphant army, this is nothing more than I would have expected; but coming as I do, to tell you of a very great disaster . . . this demonstration of your love fills me with feelings too deep for

utterance

. This has been a war of the people for the people . . . and if they desire to continue the struggle, I am still ready and willing to devote myself to their cause. True, General Lee’s army has surrendered, but the men are still alive, the cause is not yet dead; and only show by your determination and

fortitude

that you are willing to suffer yet longer, and we may still hope for success.”

At the end of Davis’s speech, somebody handed him a telegram from John C. Breckinridge. Davis read the words in silence: “President Lincoln was assassinated in the theatre in Washington.”

A few minutes later Davis spoke to his secretary of the navy, Stephen Mallory. In a sad voice, Davis said, “I certainly have no special regard for Mr. Lincoln; but there are a great many men of whose end I would much rather have heard than his. I fear it will be disastrous to our people, and I regret it deeply.”

Jefferson Davis tried to understand what Lincoln’s murder would mean for himself and his cause. Who had killed him, and why? What did this news mean for his retreat, and for his plans to continue the war? Davis would have found it hard to imagine the strength of emotions the assassination had stirred up across the country. Had he known, he might have decided to travel south more quickly.

Despite the disturbing news of Lincoln’s death, there were some people who agreed with Jefferson Davis that it was still possible for the South to keep the struggle going. On April 19 General Wade Hampton wrote to his president, encouraging him to continue the fight from Texas. “Give me a good force of cavalry and I will take them safely across the Mississippi, and if you desire to go in that direction it will give me great pleasure to escort you. My own mind is made up as to my course. I shall fight as long as my Government remains in existence. . . . If you will allow me to do so, I can bring to your support many strong arms and brave hearts—men who will fight to Texas, and who, if forced from that State, will seek refuge in Mexico rather than in the Union.”

In Washington Lincoln’s body lay all night in the Capitol. The crowds would have to wait outside. No visitors would be allowed to enter until morning. Thousands of people lined up on East Capitol Street on the afternoon, evening, and night of April 19, waiting for their last chance to see Abraham Lincoln.

The doors to the Capitol were thrown open on the morning of April 20. People passed between two lines of guards on the plaza, entered the building, and split into two lines that passed on either side of the open coffin. The experience lasted only a few moments. Visitors were not allowed to linger, and they walked past the coffin at the rate of more than three thousand an hour. Only the sound of rustling dresses and hoop skirts broke the silence. At 6:00

P.M.

the doors were closed and the public viewing ended. If they had been allowed, the people would have kept coming all through the night.

Jefferson Davis awoke in Charlotte on the morning of April 20 still determined to continue the fight. Lincoln’s death had changed nothing. Indeed, now that Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, had become president, Davis believed it was even more important not to give in. Johnson was not as generous a man as Lincoln. If the South surrendered to him, the revenge he would take would be more terrible than any suffered under Abraham Lincoln. Davis had made his decision: The Civil War would go on as long as he lived and as long as his soldiers would fight.

But Davis must have known

this.

Lincoln’s murder had placed his life in greater danger. If he was captured by Union troops, they would be tempted to take revenge for Lincoln’s murder. Davis might soon join Lincoln in death.

Stanton had chosen the cities the funeral train would stop in. Now he needed to decide who would travel on it. Just a day before the train was to depart Washington, he made his choice of men to take the president home to Springfield. He chose Brigadier General Edward Townsend to command the train and assigned the men who would serve under him.

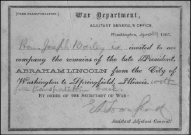

A Congressman’s ticket to ride aboard the Lincoln funeral train.

Stanton also sent Townsend his orders about how everything on the funeral train was to happen. A stickler for detail, he left nothing to chance. At least one officer would be with Lincoln’s body at all times. No one who didn’t belong on the train should be allowed on. Townsend would report by telegraph the arrival and departure of the train at each city. And the train would have to stick to its timetable. Townsend would be responsible for making sure that, in each city, Lincoln’s coffin came back to the funeral train in time for the train to leave on schedule.

Assistant Adjutant General Edward D. Townsend, commander of Lincoln’s funeral train.

Stanton issued another order on April 20. It was a public announcement offering a hundred thousand dollar reward for the capture of Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and for his coconspirators John Surratt and George Atzerodt. Six days after the assassination, the murderer was still at large. Both the fleeing Confederate president and the killer of the Union president were still on the run. To anyone who dared to help Booth during his escape from justice, Stanton promised the punishment of death.

On the same day that Stanton announced the reward, Jefferson Davis wondered if Lincoln’s murder might help his cause. “It is difficult to judge of the effect” of the murder, he wrote. “His successor [Andrew Johnson] is a worse man, but has less influence. . . . [I] am not without hope that recent disaster may awake the

dormant

energy and develop the patriotism which sustained us in the first years of the War.”

Davis was struggling unsuccessfully to make sure that his remaining soldiers had what they needed to fight. “General Duke’s brigade is here without saddles,” he wrote on April 20. “There are none here or this side of Augusta. Send on to this point 600, or as many as can be had.” In another letter Davis asked for cannons and more men. Travel was becoming increasingly difficult. On the evening of April 20, John C. Breckinridge, Davis’s secretary of war, wrote from Salisbury, North Carolina, to Davis in Charlotte: “We have had great difficulty in reaching this place. The train from Charlotte which was to have met me here has not arrived.” President Davis replied promptly: “Train will start for you at midnight with guard.”

On April 20 Robert E. Lee was at home in Richmond. He had no army to command. He knew that President Davis was still trying to continue to fight the war. Lee thought he was wrong to do so. Any further fighting must, he believed, turn into bloody, lawless,

guerrilla warfare

. Better an honorable surrender than that. Lee wrote a remarkable letter to his commander in chief. He urged Jefferson Davis to surrender: “From what I have seen and learned, I believe an army cannot be organized or supported in Virginia, and as far as I know the condition of affairs, the country east of the Mississippi is morally and physically unable to maintain the contest. . . . A partisan war may be continued . . . causing individual suffering and devastation of the country, but I see no prospect by that means of achieving a separate independence. It is for Your Excellency to decide, should you agree with me in opinion, what is proper to be done. . . . I would recommend measures be taken for . . . the restoration of peace.”

Davis never got Lee’s letter. But even if he had, it would not have convinced him to surrender. Davis still had faith that by crossing to the west of the Mississippi, he would be able to continue the war. Indeed, the arrival in Charlotte that very day of several cavalry units gave Davis new hope.