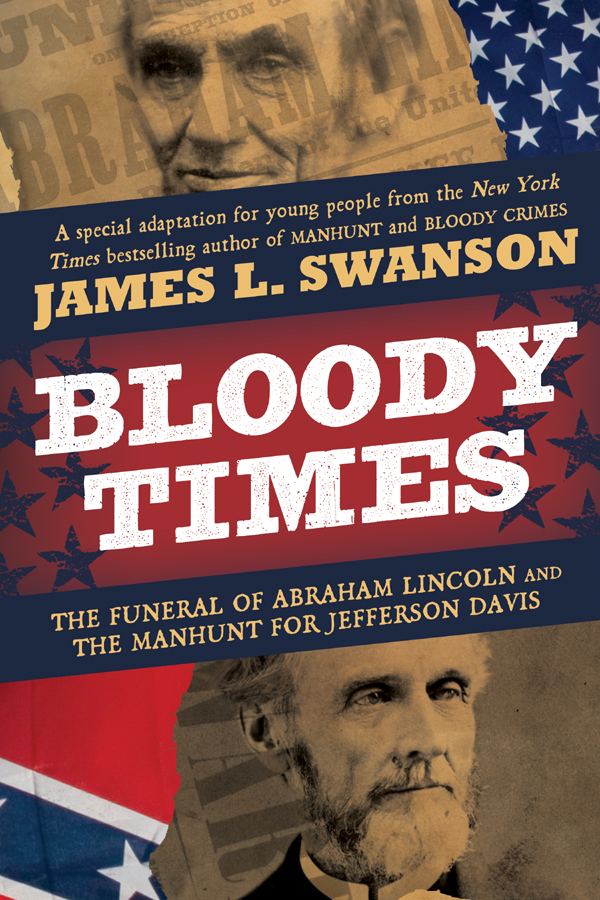

Bloody Times

Authors: James L. Swanson

JAMES L. SWANSON

BLOODY

TIMES

THE FUNERAL OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

AND

THE MANHUNT FOR JEFFERSON DAVIS

Contents

In the spring of 1865, the country was divided in two: the Union in the North, led by Abraham Lincoln, fighting to keep the Southern states from seceding from the United States. The South, led by its president, Jefferson Davis, believed it had the absolute right to quit the Union in order to preserve its way of life, including the right to own slaves. The bloody Civil War had lasted four years and cost 620,000 lives. In April 1865, the war was about to end.

In April of 1865, as the Civil War drew to a close, two men set out on very different journeys. One, Jefferson Davis, president of the

Confederate

States of America, was on the run, desperate to save his family, his country, and his cause. The other, Abraham Lincoln, murdered on April 14, was bound for a different destination: home, the grave, and everlasting glory.

Today everybody knows the name of Abraham Lincoln. But before 1858, when Lincoln ran for the

United States Senate

(and lost the election), very few people had heard of him. Most people of those days would have recognized the name of Jefferson Davis. Many would have predicted Davis, not Lincoln, would become president of the United States someday.

Born in 1808, Jefferson Davis went to private schools and studied at a university, then moved on to the United States Military Academy at West Point. A fine horseback rider, he looked elegant in the saddle. He served as an officer in the United States army on the western frontier, and then became a planter, or a farmer, in Mississippi and was later elected a

United States Congress

man and later a senator. As a colonel in the Mexican-American War, he was wounded in battle and came home a hero.

Davis knew many of the powerful leaders of his time, including presidents Zachary Taylor and Franklin Pierce. He was a polished speech maker with a beautiful speaking voice. Put simply, he was well-known, respected, and admired in both the North and the South of the country.

What Davis had accomplished was even more remarkable because he was often ill. He was slowly going blind in one eye, and he periodically suffered from

malaria

, which gave him fevers, as well as a painful condition called

neuralgia

. He and his young wife, Sarah Knox Taylor, contracted malaria shortly after they were married. She succumbed to the disease. More than once he almost died. But his strength and his will to live kept him going.

Abraham Lincoln’s life started out much different from Jefferson Davis’s. Born in 1809, he had no wealthy relatives to help give him a start in life. His father was a farmer who could not read or write and who gave Abe an ax at the age of nine and sent him to split logs into rails for fences. His mother died while Lincoln was still a young boy. When his father remarried, Abe’s stepmother, Sarah, took a special interest in Abe.

By the time Abe Lincoln grew up, he’d had less than a year of school. But he’d managed to learn to read and write, and he wanted a better life for himself than that of a poor farmer. He tried many different kinds of jobs: piloting a riverboat, surveying (taking careful measurement of land to set up boundaries), keeping a store, and working as a postmaster.

He read books to teach himself law so that he could practice as an attorney. Finally in 1846 he was elected to the U.S. Congress. He served an unremarkable term, and at the end of two years, he left Washington and returned to Illinois and his law office. He was hardworking, well-off, and respected by the people who knew him—but not nearly as well-known or as widely admired as Jefferson Davis.

It may seem that two men could not be more different than Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. But in fact, they had many things in common. Both Davis and Lincoln loved books and reading. Both had children who died young. One of Davis’s sons, Samuel, died when he was still a baby, and another, Joseph, died after an accident while Davis was the president of the Confederacy. Lincoln, too, lost one son, Eddie, at a very young age and another, Willie, his favorite, while he was president of the United States.

Both men fell in love young, and both lost the women they loved to illness. When he was twenty-four years old, Davis fell for Sarah Knox Taylor. Called Knox, she was just eighteen and was the daughter of army general and future president Zachary Taylor. It took Davis two years to convince her family to allow her to marry him—but at last he did. Married in June of 1835, just three months later both he and Knox fell ill with malaria, and she died. Davis was devastated. His grief changed him—afterward he was quieter, sterner, a different man.

Eight years later, he found someone else to love. He married Varina Howell, the daughter of a wealthy family. For the rest of his life, Davis would depend on Varina’s love, advice, and loyalty. They would eventually have six children; only two would outlive Jefferson Davis.

Lincoln was still a young man when he met and fell in love with Ann Rutledge. Everyone expected them to get married, but before that could happen, Ann became ill and died. Lincoln himself never talked or wrote about Ann after her death. But those who knew him at the time remembered how crushed and miserable he was to lose her. Some even worried that he might kill himself.

Abraham Lincoln recovered and eventually married Mary Todd. But their marriage was not as happy as that of Jefferson and Varina. Mary was a woman of shifting moods. Jealous, insulting, rude, selfish, careless with money, she was difficult to live with.

By far the greatest difference between Davis and Lincoln was their view on slavery. Davis, a slave owner, firmly believed that white people were superior to blacks, and that slavery was good for black people, who needed and benefited from having masters to rule over them. He also believed that the founding fathers of the United States, the men who had written the

Constitution

and the

Declaration of Independence

, a number of whom had owned slaves, had intended slavery to be part of America forever.

Lincoln thought slavery was simply wrong, and he believed that the founders hadn’t intended it always to exist in the United States. Lincoln was willing to let slavery remain legal in the states where it was already permitted. But he thought that slavery should not be allowed to spread into the new states entering the Union in the American south and southwest. Every new state to join the country, Lincoln firmly believed, should prohibit slavery.

Lincoln explained his views in several famous debates during his campaign for Senate in 1858. The campaign debates between Lincoln and Stephen Douglas brought Lincoln to national attention for the first time. Though he lost that Senate race, his new visibility enabled Lincoln to win the presidential nomination and election in 1860. To the surprise of many, it was Abraham Lincoln who became the president of the United States by winning less than 40 percent of the popular vote. More people voted for the other three candidates running for president than for Lincoln.

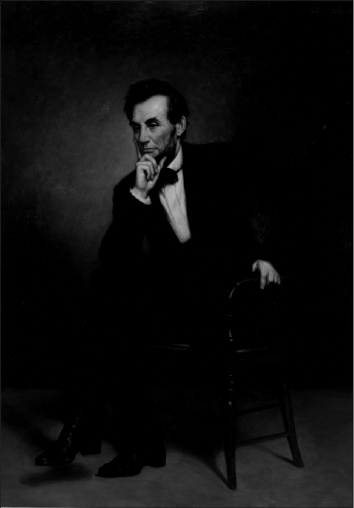

Oil portrait of Lincoln as he appeared on the eve of victory in 1865.

On the morning of Sunday, April 2, 1865, Richmond, Virginia, capital city of the Confederate States of America, did not look like a city at war. The White House of the Confederacy was surprisingly close to—one hundred miles from—the White House in Washington, D.C. But the armies of the North had never been able to capture Richmond. After four years of war, Richmond had not been invaded by Yankees. The people there had thus far been spared many of the horrors of fighting. This morning everything appeared beautiful and serene. The air smelled of spring, and fresh green growth promised a season of new life.

As he usually did on Sundays, President Jefferson Davis walked from his mansion to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. One of the worshippers, a young woman named Constance Cary, recalled the day: “On the Sunday morning of April 2, a perfect Sunday of the Southern spring, a large congregation assembled as usual at St. Paul’s.” As the service went on, a messenger entered the church. He brought Jefferson Davis a telegram from Robert E. Lee.

The telegram was not addressed to Davis, but to his secretary of war, John C. Breckinridge. Breckinridge had sent it on to Davis. It told devastating news: The

Union

army was approaching the city gates, and the Army of Northern Virginia, with Lee in command, was powerless to stop them.

Headquarters, April 2, 1865

General J. C. Breckinridge:

I see no prospect of doing more than holding our position here till night. I am not certain that I can do that. . . . I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight. I will advise you later, according to circumstances.

R. E. Lee

On reading the telegram, Davis did not panic, but he turned pale and quietly rose to leave the church. The news quickly spread through Richmond. “As if by a flash of electricity, Richmond knew that on the morrow her streets would be crowded by her captors, her rulers fled . . . her high hopes crushed to earth,” Constance Cary wrote later. “I saw many pale faces, some trembling lips, but in all that day I heard no expression of a weakling fear.”

Many people did not believe that Richmond would be captured. General Lee would not allow it to happen, they told themselves. He would protect the city, just as the army had before. In the spring of 1865, Robert E. Lee was the greatest hero in the Confederacy, more popular than Jefferson Davis, who many people blamed for their country’s present misfortunes. With Lee to defend them, many people of Richmond refused to believe that before the sun rose the next morning, life as they knew it would come to an end.