Boost Your Brain (43 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

For anyone worried about late-life dementia, that’s astoundingly good news. Vascular disease is, by and large, preventable. If we can reduce our risk for developing it, we also reduce our risk of being felled by the late-life condition we call Alzheimer’s disease.

A “Dynamic Polygon”

I have a great deal of respect for Dr. Alzheimer. He, after all, knew the disease he noted in Auguste D. differed from that which struck the very old. To reflect that reality, and the fact that the words “dementia” and “Alzheimer’s disease” are so thoroughly stigmatized, I—along with two prominent neuroscientists, Dr. Vladimir Hachinski and Dr. Peter Whitehouse—favor a radical change in terminology.

7

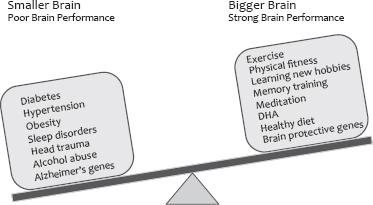

Together, we have suggested replacing the terms dementia and Alzheimer’s disease with the more respectful and less stigmatizing terms: mild, moderate, or severe “cognitive impairment.” We’ve also put forward an alternative to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, with an emphasis on the fact that most cases of cognitive impairment in the elderly are caused by numerous different etiologies and that these factors exist in a dynamic state in the brain, each capable of ramping up injury caused by the others. According to our “dynamic polygon hypothesis,” sleep apnea, insomnia, diabetes, obesity, depression, and stroke act both individually and in combination with Alzheimer’s plaques and tangles (or Lewy body lesions) to chip away at the brain. Those brain-shrinking culprits are balanced by brain reserve created by multiple brain-boosting factors, such as exercise, meditation, cognitive stimulation, a heart-healthy diet, and high levels of DHA.

Our hypothesis suggests that given the dynamic interaction of various factors involved in causing brain atrophy, treating one condition (such as hypertension) may reduce levels of another factor (such as plaques and tangles in the brain). A new discovery published in 2013 by Dr. White and his team supports our hypothesis. It shows that a subset of blood pressure medications (called beta blockers) that improve blood flow to the brain reduce not only the number of strokes in the brain but also the load of Alzheimer’s plaques and tangles.

8

This concept is further supported by the results of research by Dr. John Morris and his colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis.

9

Using an amyloid PET imaging technique, they first confirmed the high density of amyloid in the brains of patients with a genetic disposition that increases the risk for Alzheimer’s disease (called APOE 4). They then found that patients with this inherited mutation who exercised regularly had a low brain amyloid level, comparable to unaffected people who didn’t have this genetic mutation. In other words, it appears these individuals were able to use exercise to reverse the effects of an Alzheimer-related APOE

4). They then found that patients with this inherited mutation who exercised regularly had a low brain amyloid level, comparable to unaffected people who didn’t have this genetic mutation. In other words, it appears these individuals were able to use exercise to reverse the effects of an Alzheimer-related APOE 4 mutation they were born with.

4 mutation they were born with.

These exciting breakthroughs, yet to be replicated, point to the fact that we may be able to directly prevent late-life Alzheimer’s disease through the same interventions that prevent strokes and heart attacks. It’s yet more incentive to engage in brain-boosting activities throughout life, especially if you have family members who have Alzheimer’s disease.

Looking to the Future of Brain Health

I consider myself lucky to be in a field that is in the midst of unprecedented discovery. We are, in fact, entering a new era in brain health, one that will bring with it a dramatic shift in the way we view the brain throughout life.

With the explosion of interest in the field of neuroscience and the urgent need to stop age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, we can expect to see a surge of new revelations and technologies that address the factors affecting brain size with aging.

One area of particular interest to me is the effect of our increasingly wired lifestyle on brain size. We already know, as I discussed in

chapter 7

, that paying close attention and using our memory and other cognitive skills are important for maintaining those skill sets. I expect we’ll discover more about how frantically checking e-mail, being glued to electronic devices, and being in the habit of skimming information reshapes the brain. As we rely less on our brains to deeply digest the information that comes our way, to calculate math problems, or to memorize phone numbers, will the generations to come have smaller hippocampi? And to what effect, on both brain function and their future risk of developing late-life dementia? I don’t know the answer, but I do fear our patterns of technology use, constant distraction, and overstimulation will come at a cost.

Your brain health and performance are determined by a balance of factors that either shrink or grow the brain. Genes play a small role in late-life brain health: just as you may have genes that increase your risk of Alzheimer’s disease, you may also have protective genes that keep you mentally sharp.

On the other hand, technology will no doubt play a beneficial role in many ways. We may soon see, for example, devices that measure and monitor our “brain health index” (based on EEG recordings), our “brain fitness index” (based on our capacity to handle challenging cognitive tasks or on test performance), our “brain hit index” (based on sensors inside helmets), or our “brain size index” (based on quantitative MRI measurements of the hippocampus). Already I routinely obtain detailed information about hippocampal volume in my patients because I know the direct link between its size and the potential for remaining sharp for years to come. We might one day also measure the quantity of synapses in the brain (“brain synapse index”) and use that measure as an indicator of brain health and fitness throughout life. Just as you know how much money you have in your retirement account, you may one day know how many synapses you have in your “brain reserve account.”

I believe that the advance in imaging techniques will revolutionize our views of aging and what we define as “normal” versus “Alzheimer’s disease.” With new PET labeling markers (such as FDDNP) that show the presence of plaques and tangles in living people,

10

we will need to decide if these pathological clumps of toxic amyloid plaques are the culprits themselves or just the consequence of things gone wrong. Are they the fire or merely the smoke? It’s a vitally important distinction, since removing the smoke won’t stop a fire. If plaques and tangles are merely a reflection of damage to the brain, then perhaps the term “Alzheimer’s disease” will take on a new meaning. This has tremendous implications for diagnosing and labeling patients who have memory issues.

As exciting as the future of technology and testing is, there’s plenty of action ahead in the world of food and drugs as well. We’re already aware of the importance of eating well, but we’ll continue to learn more about how certain foods—from blueberries to broccoli, clams to coconut oil—affect the brain and how much we need to consume to reap rewards.

Emerging brain “superfoods” may one day contain a cocktail of herbs and supplements, such as DHA, curcumin, quercetin, resveratrol, vitamin B12, folate, Fruitflow, and huperzine. There is also a wealth of research under way into various pharmaceutical treatments for late-life dementia. Countless drug trials have failed to find a cure, but some hold promise.

I’m not terribly hopeful that a single cure—pharmaceutical or otherwise—will be found for Alzheimer’s disease and other late-life dementias. But I am hopeful about a future in which we have far better options to control various known brain drainers throughout our lives. There’s much excitement around potential “cures” for obesity, for example, through interventions that help to regulate the hormone leptin, which is critical for controlling appetite.

With a greater understanding of how to stave off brain atrophy, it’s likely that just as we have experienced an increase in life span over the past century, we will see an increase in our “brain span”—the portion of our lives that we live in peak cognitive condition. The bigger your brain size, the greater will be your brain span.

The Face Behind the Facts Is . . . You

Remember the story from

chapter 4

of my co-author, Christina? Not long after we began working together on this book, she announced she wanted to put my brain fitness program to her own (unscientific) test.

Like any other patient in my program, she completed neurocognitive testing, took blood tests for key health measures, and took a fitness test to gauge her cardiovascular health, followed by an MRI to check for any brain abnormalities and to measure the size of her hippocampus. Not too surprisingly given her youth and health history, her test results showed she was in good health, with no indicators of any problems, save a slight vitamin D deficiency.

For the next three months, she dove headfirst into her brain fitness efforts, rekindling a long-stalled running routine, dropping her worst eating habits, practicing relaxation exercises, and adding DHA to her diet. She made efforts to reduce stress and kept her brain active by immersing herself in brain-related research. As we talked over her brain fitness scores each week, it was clear that she was doing well. She shed ten pounds, began to sleep better, and reported an increase in her energy level. She even completed a half marathon.

But what about her brain? As you’ll recall from chapter 4, Christina’s hippocampus grew by a whopping 5 percent. This is the equivalent of sparing her ten years of brain aging. Not only that, but when she underwent formal cognitive re-evaluation at the three-month mark, her performance had improved in two separate tests of memory, jumping 16 percent in her speed of problem solving and 15 percent in memory performance. In short, she remembered more and performed faster.

It was a breathtaking result and something I see again and again at my Brain Center. And while Christina’s is just one story, it stands as my reminder that behind all the dry scientific studies, behind the statistics, behind the carefully controlled trials, there are real people. Given the right tools, as I’ve seen countless times in my medical practice, they can counter the worst effects of brain aging and improve their memories, their clarity, and their creativity within months.

And what about you? By now you’ve either implemented or are about to get started on your own twelve-week plan to boost your brain. I’m confident you’ll have noticeably enhanced brain performance to show for it. What then? Though you’ll be wrapping up your three-month program, don’t view it as the end. Instead, consider the habits you’ve developed as a new beginning. Make growing your brain a part of your every day, working fitness, a healthy diet, mindfulness, quality sleep, and cognitive stimulation into everything you do. And make reducing brain shrinkers your mission. Carry those habits forward and you’ll reap the rewards of a bigger, stronger brain for years to come.

Imagine that. Will it happen? It can. You now know that you have the power to change your brain. What happens next is up to you.