Boundary 1: Boundary (8 page)

"Not exactly," A.J. said defensively. "If you look at it cold-bloodedly, what we're really doing is essentially a legal form of gambling. There's a reason they call the financial section the 'Harriman Division' at Ares. This is land speculation based on the potential opening of a new frontier—something Heinlein mentioned in his story 'The Man Who Sold the Moon.'"

"In other words, it's a hustle." Jackie made no attempt to keep the sarcasm out of her voice.

"The fact is," she said forcefully, dropping her innocent pose, "that your scheme

is

against international law—going back at least to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959. The principles of which, I remind you, were reaffirmed in the treaty regarding use of the moon in 1967. Not to mention about a jillion UN resolutions that the United States is signatory to. What you're gambling on—more precisely, trying to get

other

people to gamble on—is that if you can land on Mars first, you can get at least some of those treaty provisions lifted."

A.J. and Joe were both looking defensive now—and the term "defensive," in the case of A.J. Baker, was a very difficult one to separate from "belligerent."

Joe, however, responded first. "Yes, Jackie, we're gambling—or asking others to, if you prefer. But what we're gambling on is not

whether

it will be done, but how quickly it will be done."

"What makes you think it will ever happen at all?"

"Because, to put it bluntly, Mars will eventually be habitable. The engineering to make it livable is already known to be possible, and relatively quickly—unlike the ten-thousand-year job it would be to terraform Venus. Antarctica really isn't, and there's a biosphere already on Earth that you can't risk disrupting in order to make it habitable. The Moon is a useless rock. Basically, those treaties hold because no one wants the areas involved badly enough to kick about it, and because there's no real motivation for lots of people to go there."

He took a bite, savored the flavor. "Mmmm . . . Now, if you want people to live somewhere else, you have to offer them something. And if what you want is for the place to be self-sustaining, you're talking about getting everything from farmers to miners to management people there. History has shown that, especially in frontier locations—and Mars will most definitely be a frontier—one of the big driving forces is the ability to get your

own

place relatively cheap, or potentially even 'free.' I put little verbal quotes around that because, of course, you'll be working your tail off to live on your land. You'll not be getting the best immigrants if what you do is force a lease or rental agreement on everyone. They will want to

own

the land, and I think the governments of the world will recognize that a separate

habitable

planet is an entirely different kettle of fish from some deserted, airless rockball like the Moon."

Jackie nodded. "Okay, it's not quite a con. You're right, it's a gamble. You're betting that the potential of a frontier will cause political pressure, on the one hand; and the thought of the potential profits from owning and exploiting an entire planet, on the other hand, will cause pressure from major industrial and financial interests. And all of it happening fast enough to make a difference in the laws to your benefit."

"Profit motive and a need for freedom are strong incentives. I think it's worth betting on, and so, apparently, do our investors."

"Fine. And let me tell you what

else

is true, Mr. Sudden-Expertin-History. Your parallel between the American frontier of the nineteenth century and the Martian frontier of the twenty-first conveniently overlooks the fact that a

lot

has changed in two centuries. It's not going to be Ye Plucky Pioneer racing his Conestoga in a land rush, it's going to be Ye Megacorporation gouging the hell out of everybody to

allow

them to go to Mars—on Megacorp's terms. Or do you think every would-be pioneer can build his own version of the

Nike

? If you ask me, your scheme—even if it works—isn't anything more than a fancy recipe for bringing back indentured servitude. In the name of 'freedom,' no less. And that's true even for American or European or East Asian would-be emigrants, much less—"

She broke off suddenly and took a deep breath. Then, decided she wasn't really in the mood for a full-bore argument. "Ah, never mind," she said, digging into her own food.

Fortunately, A.J. and Joe were just as willing to let it drop.

It was an old argument anyway, and one which in all its permutations the three of them had been bickering over for years.

A.J. and Joe were both libertarians in their political leanings—A.J., flamboyantly so; Joe, moderately so—and Jackie wasn't at all. As far as she was concerned, the splendid-sounding word "libertarianism," when you scratched the surface, all too often just meant "Me-me-meme-me."

On the subject of who really owned Mars—or ought to—Jackie tended to agree with her boss, Dr. Gupta.

"I see, "he'd said to her mildly once, after she explained the Ares Project's scheme." Finance Mars exploration by selling Martian land to wealthy speculators. Well, that will certainly be to the benefit of a billion of my former countrymen. Most of whom can't afford to own an automobile. Or a bicycle, often enough."

It was easy to deride government agencies for being bureaucratic. Jackie had done so herself, many times—and had to deal with NASA's often amazingly stupid decisions and procedures far more directly than A.J. ever did. But, in the end, she didn't really think that handing the world—the whole damn solar system!—over to people with the single-minded and ultimately self-centered focus of A.J. Baker would be any improvement. At all.

The problem wasn't even with people like A.J. anyway, much less Joe. The problem was that the kind of people they'd get to provide them with the sort of financial backing they needed usually did

not

look at the world the way they did. A.J. might be self-centered in terms of his interests and his personal focus, but he wasn't a damn bean counter. Money, as such, ranked so far down on his list of priorities that it barely made the list at all—and then, only as an afterthought. Allowing for his more practical nature, the same was true of Joe.

Jackie doubted that the Ares Project's fund-raising scheme would really work, in any event. She knew Ares had picked up enough financial backing over and above the prize money to keep their operations running—albeit always on a shoestring budget. But she thought their assessment that a successful landing on Mars would start unraveling almost three-quarters of a century's worth of international treaties forbidding the private exploitation of Antarctica and extraterrestrial bodies was . . .

The proverbial pie in the sky. If anything, she thought it was more likely that the treaties would be strengthened. Nor could she really envision any government—certainly not ones as strong as the United States or China or the European confederation—allowing any private enterprise to build spacecraft which, push comes to shove, could serve as platforms for weapons of mass destruction.

But, she reminded herself again, there was no reason to turn the subject into a loud argument over this particular meal. And who knew? When the dust all settled, they might wind up with an immensely complicated mixture of public and private methods. It had happened before, plenty of times. The kind of compromise that satisfied nobody, but didn't create enough resentment for anybody to really want to pick a fight over.

A.J. still seemed to be a bit sullen. But Joe apparently shared Jackie's sentiment.

"Enough of that," he said, pushing away his plate but obviously referring back to the earlier dispute. "Come one, Jackie, let's get to the good stuff. Tell us what it was like to test a NERVA rocket!"

Helen gritted her teeth, willing herself to keep still in her chair. It helped that she had clamped both hands on the armrests to make

sure

she didn't move. If she let go of the armrests, she'd probably leap straight over the three rows of seats ahead of her and strangle Dr. Alexander Pinchuk with her bare hands.

Helen had first encountered Dr. Pinchuk in her second semester as a graduate student. He'd been a visiting professor. Within a month, she had come to detest the man. Nothing in the years that came after, as she encountered Dr. Pinchuk time and time again— either personally at conferences or indirectly in professional journals—had changed her opinion except to deepen it.

Wine improved with age. Dr. Pinchuk did not. The sarcastic nickname he'd been given by graduate students—

Alexander the Great

—had derived from the man's egotism. A decade and a half later, coming toward the end of a career that had never been very distinguished, Pinchuk was as sour as vinegar.

Dr. Myrtle Fischer, an old classmate from those graduate student days, had hinted to Helen that she might want to attend Pinchuk's talk at the conference. Not that Helen had really needed the hint, given the title of the talk.

Frauds, Fakes, and Mistakes: An Overview of Questionable and Falsified Paleontological Evidence and Methods.

Leaving aside Helen's personal dislike for Pinchuk—she'd spent some considerable time avoiding him over the past many years; said avoidances including one outright rejection of a pass—she'd also taken him to task in several articles and at least one conference for sloppy fieldwork, something that he'd been perennially guilty of.

Pinchuk, among other things, had a nasty streak. He not only kept grudges, he fed them and bred them.

At first, the presentation seemed a good review of the history of the field, with a focus on misperceptions and outright fakery. But soon a theme emerged, wherein Pinchuk kept returning to the present and asking the question of whether such a fraud could be perpetrated in modern times. Each time, presenting a little example of how such a thing might be done. And each little example was, in fact, clearly drawn

from her own dig.

Without saying anything directly, the slimy bastard was implying that she'd faked Bemmie!

The fact that the accusation bordered on the ludicrous wouldn't necessarily keep anyone from believing it. Dr. Pinchuk had done his research well. Helen was a bit astonished, in fact, when she finally realized how much effort he'd put into it.

The approaches he described would, in fact, make it possible to create a fake even as complex as

Bemmius

, given the advances of current technology. People would ignore, or be unaware of, the other facts—for instance, that to

make

such a fake dig and set it up as described would take far more money and time than she'd received in grants over the past ten years. And that he was implying that the Secords were also in on the scam, as were all of Helen's associates and assistants.

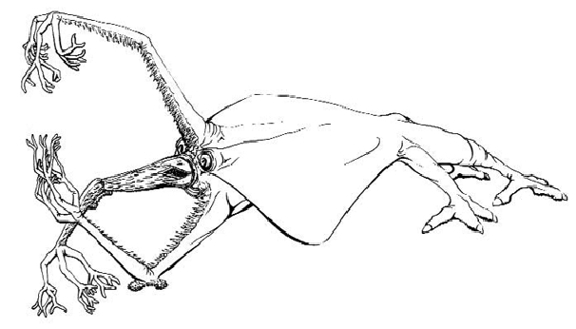

Original drawing by Kathleen Moffre-Spoor.

Original drawing by Kathleen Moffre-Spoor.

That made her even madder than the accusations against herself. She'd been prepared for something to be brought out against her, though the brazen effrontery of this approach went far beyond anything she imagined, but not for accusations against her friends.

And now she was aware of the surreptitious glances being sent in her direction. She wasn't the only one who was catching Pinchuk's references. She wondered if it would do more harm than good to try to confront him.

But . . . no, he was surely ready for that. If he'd spent this much time preparing what was obviously

both

an actually worthwhile paper

and

a carefully crafted strike at her, he wouldn't have neglected to cover the likelihood of her presence.

She could just ignore it, but that might give it more credibility. Helen ground her teeth together as Pinchuk unctuously began a discussion of another possible technique that "the paleontological field must keep vigilant watch for."

Just as she felt she couldn't possibly keep seated any longer, someone else spoke.

"Pardon me, Dr. Pinchuk."

That deep, warm voice, clearly audible around the auditorium without benefit of microphone and speakers, yanked Helen's head around almost as though by a string. It was the voice she'd been dreading all weekend, since the big annual paleontological conference began.

Dr. Nicholas Glendale rose from a seat in the back as Pinchuk recognized him.

"Overall, Doctor, an excellent piece of work," Glendale began. Helen's heart sank. Attacks from Pinchuk she could handle. Overall, she outpointed him professionally—by a big margin, in fact—and everyone knew it. But Glendale was, quite honestly, out of her league. As a paleontologist, Helen today was probably just as good—better, in fact, in the field. But in terms of reputation and professional politics, there was no comparison.

"But while it's certainly instructive to think on past events," Glendale continued, "I think you are missing an opportunity with your review of potential techniques for modern fakery."

She could make out the barely restrained grin on Dr. Pinchuk's face very easily. "Indeed, Doctor? How so? I would be glad to elaborate on any of the points I have made so far."