Brain Trust (5 page)

Authors: Garth Sundem

Iyengar explored the proverb “Success is

getting what you want, but happiness is wanting what you get,” with college seniors entering the job market. Seniors who were maximizers completed exhaustive searches and took jobs paying on average 20 percent more than satisficers, who spent much less time searching and took lower-paying jobs. But satisficers were measurably more satisfied with the jobs they landed—perhaps because maximizers relied more on external than internal measures of success in job seeking, and were more aware of the opportunities that didn’t pan out.

Ian Stewart, mathematician, prolific puzzle author, and very fun person to chat math with, explains the following best card trick I’ve ever seen, invented by mathemagician Art Benjamin at Harvey Mudd College.

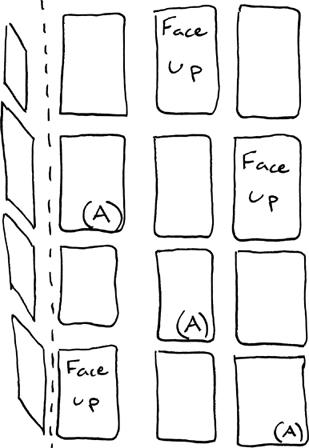

First, prepare a stack of sixteen cards so that cards 1, 6, 11, and 16 are the four aces. Now deal them facedown in four rows of four. Turn up cards 3, 8, 9, and 14 to make the arrangement shown on

this page

.

OK, you’re done with the setup and ready to start the trick proper. Ask your dupe to imagine the grid as a sheet of paper and to “fold” it along any straight horizontal or vertical line between cards (as shown on

this page

).

Continue “folding” along any lines until you’ve restacked the cards into one pack of sixteeen. Done right, twelve cards should be facedown and four should be faceup (or vice versa). Of course, the trick seems destined to return the original four faceup cards. And that would be neat. But what’s even neater is that no matter

how you fold the grid of sixteen,

the four cards that face opposite the others are—wait for it … wait for it—the four aces!

I had to do this trick three times to believe that it actually works. (It does.) Alternatively, I could have listened more closely to Stewart’s explanation.

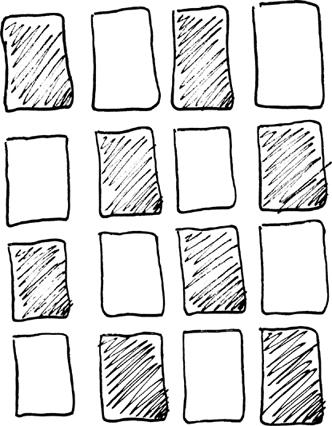

“The number two is very important,” he says. Odd and even is a fundamental property of mathematics, and in this trick means that if you flip a card an even number of times, it ends with its original up side facing up. If you flip it an odd number of times, the side that was down faces up. Now imagine arranging this trick’s sixteen cards in the pattern of a chessboard, as shown on

this page

.

However you fold a chessboard, all the white spaces undergo exactly one more or one fewer flip than the black spaces—one is odd and one is even—and so no matter how you fold chessboard-patterned cards, they will eventually turn into a pile of sixteen cards all facing the same way. Try it. But in this trick, you didn’t arrange the cards like a chessboard, did you? No. Exactly four cards in this trick’s setup differ from the chessboard pattern. And so these same four cards will point the wrong way in your folded stack.

Of course, these cards are the four aces.

Ian Stewart studies animal gaits and knows

why a cat always lands on its feet. It’s a surprisingly interesting question: A nonrotating, upside-down cat that becomes a nonrotating right-side-up cat seems to break the laws of mechanics. Where does this phantom rotation come from?

“Our first cat couldn’t do it,” says Stewart, “and my wife tried to train him by holding him upside down above a cushion.” Presumably this was for the cat’s safety and not purely for entertainment. (Yes, after reviewing a draft of this entry, Stewart confirmed safety was indeed the motive.) What cats other than Stewart’s rotationally challenged feline do is use the physics of merry-go-rounds. They twist their back legs in one direction and counterbalance by twisting their front legs in the other direction. Great: equal and opposite.

But here’s the trick: The cat pulls in its front legs and extends its back legs, so that its front undergoes more rotation (just like the body-in/body-out speed trick of merry-go-rounds … that is, before they were banned from American playgrounds for reasons of safety and pediatric wussification). Then the cat repeats and reverses the operation, extending its front legs, which act as a rotational anchor allowing the constricted back legs to catch up.

Voilà! Without turning Newton in his grave, the cat has turned itself butter-side up! It’s a neat trick; you can see it happening in slow motion at

National Geographic

’s website by video searching “cat’s nine lives.”

Puzzle #1:

Math Is Too Sexy

As you know, math is extremely stylish. Use well-known physics equations to transform “mat = hematic” into “G = uccci.”

Betting seems like you versus the odds, but in fact it’s a mano a mano competition between you and a bookie. And unfortunately, the game’s rigged: The standard bookie payout is 10/11, meaning that a win pays ten dollars but you pay eleven dollars for a loss. So bookies don’t gamble: They set a statistically fair line so that (theoretically) half the money is bet one way and half the money is bet the other. Each loser pays for a winner, and the bookie cleans up on transaction fees.

It’s exactly like roulette: Over time, the losers pay the winners and the 2/34 times the ball lands on green, the casino gets paid.

OK, sports betting isn’t exactly like roulette. In sports betting, humans set the opening line. For example, bookies predicted the Lakers and Celtics would score a combined 187 total points in Game 7 of the 2010 NBA Finals. You could’ve bet over or under this total. Or bookies had the Colts winning by 5 points over the Saints in the 2010 Super Bowl. You could’ve taken Colts -5 or Saints +5.

With the bookies’ rake (much different than the sports fund-raiser rookies’ bake), you have to beat the line more than 52.4 percent of the time to make money. And it comes down to this: Who’s got the best kung fu, you or the Wookiees—er … bookies?

Wayne Winston, decision science professor at Indiana University, Mark Cuban’s former stats guru for the Dallas Mavericks, and author of the book

Mathletics

has especially strong kung fu. (His website,

www.WayneWinston.com

, is a cornucopia of statistical awesomeness for all things sports.)

One of his nicer attempts at a Shaolin throw down was trying to beat the NBA over/under by including referees’ influence on total score. Basically, a ref who calls more fouls creates a

higher final score—free throws are easy points and players in foul trouble can’t defend as aggressively. This is what former NBA referee (and convicted felon) Tim Donaghy did—he called more fouls or allowed teams to play in order to manipulate the total points scored. But other referees are naturally permissive or restrictive. For example, from 2003 to 2008, when the referee Jim Clark officiated, teams went over the predicted total 221 times and under the predicted total 155 times (more ref data at

Covers.com

). Bingo! It looks like you can make money! Just bet the over whenever Jim Clark’s on the ticket!

But it’s not that easy. First, there are three refs on any NBA ticket. Averaging their predicted over/under makes any single ref less powerfully predictive. And you’re also counting on the idea that past performance is going to equal future prediction. This is a problem with most mathematical modeling: You look into the past and hope like heck the future’s going to be similar. But what if Jim Clark realized he’d been calling games too tight and decided to ref a little differently this year? You’d be out of luck.

As was Wayne Winston, who found refs could help him beat the NBA total over/under more than 50 percent of the time, but not more than the 52.4 percent he needed in order to make money. Unfortunately, he says, bookies in the big three sports—football, baseball, and basketball—are very sophisticated and tend to set very good opening lines—you’re as likely to win on one side of the line as you are on the other.

But what happens after a bookie sets a line? Well, it moves based on how people bet. If a basketball over/under started at 187 points and for whatever reason more people bet over, the line might jump to 190 points to encourage equal money on either side. Remember, bookies don’t want risk and to avoid it, the over has to match the under.

So when an opening line is released into the wild, it goes from being a statistical system to being a human system. And human

systems are beholden to irrationality. For example, take Roger Federer versus Rafael Nadal. You’d have a tough time beating the line in Vegas, but what about in Zurich or in Madrid? People like to bet their home team, and so after a statistically accurate opening line hits the streets in Switzerland, Swiss bookies are likely to see more money bet on Federer. To avoid risk, the line would adjust to encourage bets on Nadal. If Vegas thought Federer/Nadal was an even match, a bet might pay 1:1, but a bookie in Geneva might give people 1:1.2 odds to encourage the otherwise-inclined Swiss to bet Nadal.

When you find inequalities between bookies, what’s the best thing to do? Well, one option is arbitrage: You can bet both. Imagine putting $100 on Federer with a Spanish bookie paying 1:1.2, and $100 on Nadal with a Swiss bookie paying 1.2:1. No matter who wins, you lose $100 and win $120. But, Winston points out, differences in bookies are likely to be very small and so only big-money bets earn anything appreciable in arbitrage. And throwing big money at a Swiss bookie might change the line. For example, $100,000 on Nadal in Geneva might balance all the hometown fans betting Federer, swinging the payout back to 1:1. And arbitrage websites are likely to rake a little more than the standard 10/11 of Vegas bookies. That said, it’s worth keeping your eyes on rivalries, says Winston. “It’s probably a crime to bet Serbia in the World Cup if you’re living in Croatia.”