Bread Matters (24 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

CLASSIC WHEAT LEAVEN SYSTEM

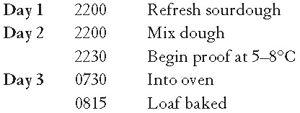

The rye system would work quite well for someone who is out all day. You refresh your sour one evening and then make bread the next evening. The only risk is that if the bread is slow to prove, you may have a late night. What happens, however, if you refresh your sourdough at ten o’clock one night, intending to make rye bread the following evening, but you are unexpectedly delayed and do not get home until ten? If you leave the sourdough for another day, it could get too acidic and the yeasts might lose vigour. If you do another refreshment you will have ten times as much refreshed sour as you want, or you will have to throw some away. The alternative is to make the dough at ten o’clock at night (it takes only a few minutes if it’s a rye bread), and prove the bread slowly in a cool room or in the fridge. With a bit of luck, it will have risen by morning and you can put it straight in the oven and have it baked before going out. The timeline would look like this:

RYE SOURDOUGH SYSTEM – CHILLED PROOF

The rye sourdough refreshment, which was arbitrarily fixed at 20 hours in the ambient example above, can in fact last from four to 24 hours, providing considerable extra flexibility. The beauty of the rye sour is that it does not have to be slowed down by chilling at the refreshment stage because some extra acidity in the final dough will not affect the dough structure, merely its flavour.

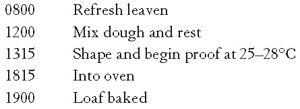

The wheat leaven is different. If a wheat production leaven is over-fermented, it will bring too many acids into the final dough and the gluten will be quickly over-ripened. This causes a breakdown of the dough structure, which results in a ragged, sticky, poorly risen loaf. So, if the leaven refreshment period of four hours at ambient temperature does not fit in with your plans, you can extend this to 12 to 24 hours in the fridge. A cold leaven and ambient final dough system might look like this:

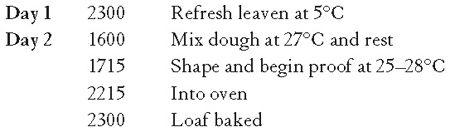

WHEAT LEAVEN SYSTEM – CHILLED LEAVEN, AMBIENT PROOF

This lengthens the leaven refreshment stage to 17 hours, but it still requires the main dough to be made early in the evening if the bread is going to be out of the oven at a reasonable time. If the proof time, too, is extended by using a lower temperature, it becomes possible to have both the long processes (leaven refreshment and proof) occurring at times when you are either asleep or out.

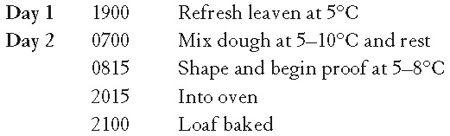

The following timing has a 12-hour overnight leaven refreshment and a 12-hour daytime proof. If the bread has not fully proved by the time you get in at night, you can always finish it off with a little warmth.

WHEAT LEAVEN SYSTEM – CHILLED LEAVEN, CHILLED PROOF

These are, I stress, indicative timings only. The one thing that can be said for certain about natural fermentations is that they are not completely predictable. But they do have the great advantage that they are generally slow, and can be made even slower with judicious temperature adjustments.

What the above timings do show is that slow baking is not incompatible with a busy life. And if the gratification seems rather delayed, remember that slow bread is more nutritious, more digestible, better flavoured and longer keeping than its fast-fermented counterparts.

What do I do with my sourdough between baking sessions?

I encounter many able and enthusiastic bakers, both domestic and professional, on the courses that I run. Quite a few of these are intimidated by sourdoughs, not least because looking after them seems to be such a hassle. This widespread perception is not dispelled by baking books that treat leavens and sourdoughs as if they need constant and fiddly attention. The notion of ‘feeding’ a sourdough may be the source of the problem. If empathy spills over into anthropomorphism, it is easy to see how people might worry that they are doing something wrong as their precious sourdough declines into a dormant sludge. It is only human to associate health with some signs of active life. So they fuss and poke, sprinkle and stir, or suffer pangs of remorse as ‘feeds’ are missed. People have recounted to me the demise of their sourdough in terms that could hardly be more guilt-ridden if they were confessing to starving the family cat. There’s probably a psychotherapist somewhere doing a roaring trade in sourdough bereavement counselling.

All this angst is unnecessary. You need only think about your sourdough when you want to make a batch of bread. No hassle and no stress.

Once a sourdough or leaven is established, it is generally in one of two phases – maintenance or production. In the maintenance phase, a quantity of sourdough is held (in or outside a refrigerator) as a reservoir of yeasts and bacteria. In the production phase, it is refreshed with the addition of new flour and water. The greater part of this refreshed sourdough is used to produce bread, with the unused part returning to the maintenance phase until it is next needed for production.

Instead of ‘feeding’ the sourdough, we are incorporating it all into a bigger entity, the production sourdough. The piece that we keep back as a future starter is therefore a mixture of the old sour and the fresh flour and water. This is important because it guarantees that when an old sour is refreshed, a correct balance of old and new material is maintained. By contrast, the problem with ‘feeding’ is that if you simply make small regular additions of flour and water to a permanent stock sourdough, you are likely to cause a build-up of acidity, which will make it progressively more difficult for the yeasts to thrive.

One solution to the latter problem that I have come across is periodically to ‘wash’ your starter, which is a way of diluting its acidity and giving the yeasts a better chance. But this is yet another job waiting to be overlooked, another breeding ground for guilt and a great big waste of time.

Constructive neglect

So, the question that everyone baking with sourdough wants answered is: what do I do with it between bakes?

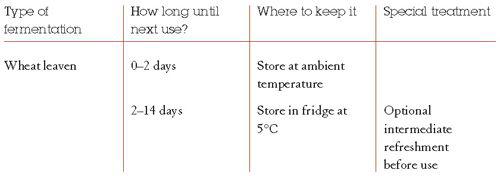

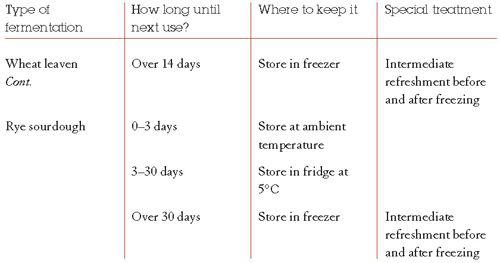

To which I respond: as little as possible, provided that it will still work when you next want to use it. That may be tomorrow, next week or in a month’s time and the gap between outings will dictate your intervening treatment. First, a few principles, and then a simple look-up table as a guide to future action.

When a sourdough is left unrefreshed, first the yeasts, then the lactobacilli run out of nutrients; some of the yeast cells will die if the acidity goes beyond a certain point, others will go into a dormant state, as will the bacteria. The speed at which this occurs is dependent on temperature. If a sour is left in warm conditions it will grow more acid more quickly and it may also fall prey to extraneous moulds. So, if more than two or three days are likely to pass before the sourdough is used again, it is best to store it in the fridge. In this, as in other ways, rye sours are more tolerant than wheat leavens, but the basic idea is the same for both.

If your sour was viable when you last used it, it should keep for many weeks and revive easily. I keep (in the fridge) a bucket of old rye sourdough that is many months old; all I ever do to it is stir in the grey-brown liquid that settles on the surface and scoop out about 50g of sour to demonstrate how easy it is to maintain a sourdough. I never add fresh flour to this old sour. I take this icy-cold, not very fragrant 50g and mix it with 150g wholemeal rye flour and 300g very warm water. I cover it and leave it in the bakery, which is usually at about 25°C. Without fail, 16 hours later, I have a bubbling, pleasant-smelling, utterly normal refreshed rye sourdough. It is as simple as that.

Broadly the same holds for a wheat leaven. However, the usual four-hour period for a wheat refreshment may be insufficient for a really dormant old leaven to come to life again, in which case it may be worth leaving it to ferment for a bit longer.

Intermediate refreshment

If you have doubts about the viability of your old sour, you may want some prior assurance that it really will work before you commit to a full baking session. This is easily achieved by doing an extra refreshment the day before you would otherwise have begun the baking cycle. There is one problem: by doing two refreshments instead of one, you may end up with more sourdough than you want. So, you either make a bigger batch of bread, or you give or throw away some of your sourdough. Alternatively, you could freeze the unwanted portion, making a note of what stage it had reached. This could be used at a later date if a sudden increase in production were called for, or if some disaster had befallen your day-to-day sour.

If you think you are unlikely to use a wheat leaven for more than a fortnight or a rye sourdough for more than a month, it is probably best to freeze them. Freezing tends to reduce the power of the natural yeasts, if not the bacteria, so it is wise to refresh a sour immediately before putting it in the freezer and to give it an intermediate refreshment after it comes out, just to make sure that it has regained full vigour. You will need to work out what to do with the extra sourdough thus generated.

Storing leavens and sourdoughs