Bread Matters (20 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

140g Water

645g Total

Bowl of sunflower seeds for dipping

Mix all the ingredients together into a very soft dough at about 30°C. Using wet hands, form the dough into a smooth rectangle the right size for your tin, then dip it into the bowl of sunflower seeds, rolling it gently so that seeds stick all over the surface of the dough. Pick it up and drop it carefully into a well-greased tin. The recipe should make enough to fill a generous ‘small’ tin, with a capacity of around 500ml, just over half full.

Cover and put in a warm place (28-30°C if possible) to prove. This can take anything from 2-6 hours, depending on the vigour of the sourdough and the warmth of the conditions. Bake in a fairly hot oven (200-210°C), reducing the heat a little after 10-15 minutes. This bread is baked at a slightly lower temperature than plain Russian Rye Bread because the seeds on the outside, with their high natural oil content, can turn bitter if too highly fired.

Borodinsky Bread

Borodinsky was the doyen of Russian breads when I lived in Moscow in the late 1960s. As with all good things, it wasn’t always available. News would spread on the grapevine if a certain bread shop had a batch of Borodinsky and it would sell out in minutes.

Officials at the museum of bread in St Petersburg deny that there is any direct evidence of a connection between this bread and the Battle of Borodino, but I heard of a radio broadcast in which a well-known food historian insisted that there was a link, if only in folklore. It doesn’t really matter, because the story is a good one.

The village of Borodino was the site of a decisive battle when Russian forces confronted Napoleon just outside Moscow in 1812. Although Napoleon subsequently entered a semi-deserted Moscow, he was harassed by Russian partisans and eventually lost most of his army in the winter retreat. So for Russians, the battle has a powerful patriotic significance. The story goes that, on the eve of the fight, the wife of a Russian general wanted to bake some special bread to encourage the troops. She found coriander ripening in the early September sun and crushed some seeds to flavour her loaves. And so it was that Borodinsky acquired a heroic status among breads, through association with a crucial event. If Britons took their bread as seriously as Russians, it might be Waterloo or Trafalgar Bread that adorned our shelves instead of…‘Mother’s Pride’.

In Russia the sweetness of Borodinsky is provided by a rye malt called

suslo,

which has the appearance and viscosity of old engine oil. I have substituted a mixture of molasses and barley malt, which comes fairly near to the real thing. If these are hard to find, ordinary black treacle will do, though it is not quite malty enough.

Eat Borodinsky in open sandwiches with smoked salmon or salted herring, savoury or sweet spreads, soups or salads. It keeps for a good week. Then try it toasted with bitter marmalade. Victory shall be yours.

Makes 1 small loaf

270g Production Sourdough (see page 165)

230g Rye flour (light or wholemeal)

5g Sea salt

5g Coarsely ground coriander seeds

20g Molasses

15g Barley malt extract

90g Water (at 35°C)

635g Total

Whole coriander seeds, to sprinkle in the tin

Coarsely ground coriander seeds, for the top of the loaf Grease a small bread tin with butter or a hard vegetable fat. Sprinkle a few whole coriander seeds over the base of the tin. The grease should stop them rolling around and all gathering in one place, so it is a good idea to grease even non-stick tins for this bread.

Use the production sourdough 12-18 hours after it has been refreshed. Mix all the ingredients thoroughly into a smooth, soft dough. The mixture will be too sloppy to mould on the table so, wetting your hands and a plastic scraper, scoop it into a ball and smooth it into a loaf-shaped rectangle. Enjoy the slippery, mud-pie feeling and the fragrance of this wonderful dough. Drop the glistening pillow of dough very carefully into the greased tin, trying to avoid scraping any grease from the sides. The tin should be just over half full of dough at the beginning of proof. Do not be tempted to fiddle with the dough once it is in the tin, even if it has gone in a little lop-sided; it will find its own level. The most you should do is to smooth the surface of the dough if it looks very stippled or uneven. Wet your hand and use the back of your fingers for this. Never, incidentally, follow the fatuous advice to ‘press the dough into the corners of the tin’. At best, this will destroy the shape you have carefully created by moulding. At worst, it will key the dough into the seams of the tin, making it much more likely to stick.

Leave the bread until it has risen up the tin appreciably. If it was just over halfway up when you put it in, it should reach the top of the tin when fully proved. This may take 2-6 hours, depending on the warmth of your kitchen and the vigour of your sourdough.

The lack of a tenacious gluten structure in all-rye breads means that the dough tends to split into a crazed pattern as it reaches full proof. This is nothing to worry about. If the dough surface has dried out (if you can touch it without any dough sticking to your finger), you will need to moisten it a little so that the coarsely ground coriander sticks. Do not be tempted to spray the top with water because some will inevitably run down the sides of the tin, making it less likely that the loaf will come out after baking. Use a soft brush with some warm water and carefully moisten just the top of the loaf. Then sprinkle it generously with coarsely ground coriander.

Immediately put the loaf into a hot oven preheated to around 220°C, turning the heat down to 200°C after 10 minutes. Bake for about 40 minutes. Borodinsky takes more colour than plain rye breads because of the extra sugars in the shape of the molasses and malt. If your loaf is getting too dark, shield its top crust with a sheet or two of baking parchment towards the end of baking. The loaf may begin to shrink away from the sides of the tin when it is done. If it doesn’t come out of its tin immediately, leave it to sweat for a few minutes, then try again. If it is still reluctant to move, slide a plastic scraper down between the loaf sides and the tin to break any sticking points.

Leave Borodinsky to cool completely before wrapping it in cellophane or a polythene bag. Rest it for a day before eating. You may notice that the crumb goes darker as the days pass. I don’t know why this happens.

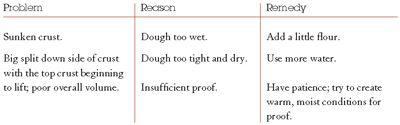

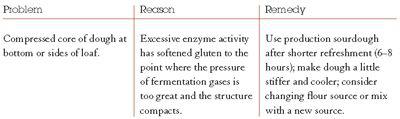

Troubleshooting 100 per cent rye breads

Breads made entirely with rye flour can produce their own distinctive challenges. Here are a few typical problems and ways of dealing with them:

Caraway Rye Bread

Caraway is a popular flavour found in rye breads from Scandinavia to the Ukraine. In Moscow, Rizhsky (Riga) bread used to be second only to Borodinsky in bread lovers’ estimation. This recipe is based on breads from Latvia and Estonia and is similar to the German

Schwarzbrot,

although that is not literally a black bread. It is a sourdough rye and wheat bread in which the two grains are present in equal quantities. The wheat flour gives the dough sufficient structure to make a freestanding loaf possible, though it can equally well be baked in a tin. Some traditions call for the use of a little baker’s yeast in addition to the sourdough. I find that the extra yeast hurries the dough along too much and produces a drier, more crumbly texture, but if time is short this may be your only option.

A first rise is suggested for this bread in order to allow some ripening of the gluten from the wheat flours in the dough. There should be adequate flavour from the sourdough and the caraway.

Makes 1 large or 2 small loaves

350g Production Sourdough (see page 165)

150g Rye flour (light)

100g Stoneground strong wholemeal wheat flour

200g Strong white flour

10g Caraway seeds

5g Sea salt

200g Water

1015g Total

Use the production sourdough 8-18 hours after refreshment; the longer the time, the more pronounced the acidic flavour. Mix everything together into a soft dough, aiming to finish it at around 28°C.

Some kneading is required to develop the gluten in the wheat flour, but you will notice that the presence of the rye flour makes for a softer, stickier dough. If you intend to mould this as a freestanding loaf, you will need to tighten the dough up just a little so that it is possible to knead it on the worktop without too much sticking. However, if you prove it in a basket or cloth-lined bowl you can contain a very soft dough’s tendency to flow. The softer the dough, the more open the internal structure and the more attractive the eating quality.

After initial kneading, cover the dough and allow it 1-2 hours to rise. If you are pushed for time, you can shorten or omit this stage. You will not notice much expansion even after 2 hours, but the wheat gluten will have relaxed and softened, making it easier to mould the dough. Divide the dough in half if you want small loaves. Gently press the dough into a rectangle and then roll it up towards you, finishing with a fat sausage.

For a freestanding loaf, deftly roll the sausage backwards and forwards a few times, with your hands moving gradually from the middle to the edges to form slightly tapered ends. Put the loaf or loaves on a baking tray and brush with a little water to ensure that the dough surface remains moist during proof.

To prove in a cloth-lined wicker basket or

panneton,

dust the lining of your basket well with rye flour or wholemeal wheat flour, dip the moulded dough piece into the same flour and lay it gently in the basket. What will eventually be the bottom of the loaf, which is the side with the seam created by rolling up the dough as it was moulded, should be facing upwards at this stage. Do not prod or poke the dough, even if it is lying a little unevenly: it will find its own level as it proves.

Enclose the basket or baking tray loosely in a polythene bag and put it in a warm place to prove, preferably with a little moisture, perhaps from a cup of boiled water placed next to the basket, to stop the dough surface drying out. Proof will take 2-4 hours, depending on the conditions and the vigour of your sourdough. When you judge the dough to have expanded to somewhere near its maximum extent without collapsing, tip the loaf gently out of the basket on to a baking tray. Depending on the type of basket used, the loaf may come out with attractive striations or the imprint of the lining material. If you want to keep these features, by all means do so. If, however, you want to create the slightly glossy, leathery crust typical of this kind of loaf, clear any loose flour from the surface of the dough and then gently brush it with warm water, taking care not to leave a ‘tide mark’ round the sides, but also avoiding a puddle on the tray.

Carefully cut the loaf with 5 or 6 slashes at an angle across the top. Try not to press down very much as you cut, otherwise the knife or blade may drag into the dough and cause some deflation of the structure.

Bake in a hot oven (230°C), reducing the heat to 210°C after 10 minutes or so. Large loaves will take about 45 minutes, small ones about 35 minutes. After baking, an immediate wash or spritz with hot water will soften and shine the crust a little. For a varnish-like finish, brush on the cornflour glaze on page 249.

Whole Grain Rye Bread

This style of bread is often described as pumpernickel. Although pumpernickel is usually made with rye, there are similar wholegrain breads in Denmark using coarsely kibbled wheat. A tasty and healthy variation is to include a proportion of sunflower seeds with the kibbled grain.

Try to use a tin that, when exactly full of dough, produces a brick-like shape with an almost square profile. Though by no means essential, this will produce nice-looking slices of bread. Incidentally, you should not be discouraged from making this bread by bad experiences with the foil-wrapped slices of cardboard bearing the name pumpernickel that languish on the shelves of healthfood shops and supermarkets. Pumpernickel-type breads have, to their great detriment, been categorised as ‘long shelf-life’ products. It is true that they keep well, even without preservatives, because of the lactic and acetic acids generated by the sourdough fermentation. But acidity prevents mould formation; it does not prevent the gradual hardening of starches that begins the moment bread is baked (unless it has been spiked with artificial enzymes). So by the time these thinly sliced breads reach the end of their six-month shelf life, they are practically mummified. If you bake your own, however, you will be able to enjoy wholegrain bread at its best – succulent, chewy-textured and nutritious.