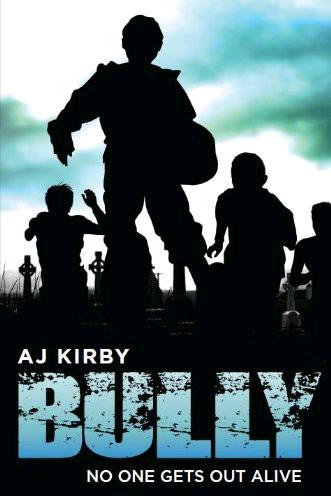

Bully

Authors: A. J. Kirby

Bully

By

A J Kirby

A Wild Wolf Publication

Published by Wild Wolf Publishing in 2009

Copyright © 2009 A J Kirby

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publishers, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed by a newspaper, magazine or journal.

First print

All Characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

ISBN: 978-0-9562114-5-3

www.wildwolfpublishing.com

Cover Art by Nick Button

www.nickbutton.co.uk

"For John,

The spirit of Elvis lived in you,

You'll be sorely missed."

Chapter One

“

Singin’, this’ll be the day that I die.”

Books and film tell me that at this very moment I should be enveloped in a great shining white light. They tell me that I’ll kind of mellow out the pain and simply settle into being guided down that conveyor belt into nothingness. Maybe books and film tell us this so we don’t simply scream the place down in rage and fear. Maybe they don’t want to turn us into dribbling wrecks at the thought of what death really is…

I can’t see any white light. I don’t feel mellow. Instead, my sensory perception is almost overwhelmed by the agonising pain in my chest. And it is represented by the colour purple. Angry, hopeless purple. It feels as though I’ve had a spear driven into the very folds of my heart and some mischievous demon is wiggling it about, tearing at the wound. I don’t think that I’ve blacked out at any point in the last few moments since it happened. My body won’t let me. It won’t let me surrender or enjoy any of it.

Some people around me look as though they’re enjoying it. The guy next to me has this big shit-eating grin on his face as he revels in the loss of control and responsibility. I think he could be Sergeant Davis, a man I’d once thought too serious to be taken seriously. And now look at him. Despite my own pain, I feel Davis’s shit seeping out of his fatigue pants; hell, its being sieved out of his pants so I get the pure unadulterated core of it, right on my face. I can’t move my arms to shield myself.

Someone’s murmuring something somewhere. Somebody else is screaming. They could be privates that were under my command, but I can’t tell any more. My own throat feels as though it has been cut. I can’t gulp back the swimming pool of saliva which is in my mouth, and for a moment, I really believe that spit is going to be the ultimate cause of my death.

But spit is just a bi-product. The real cause of the excruciating last chapter of my life is the damn explosion which ripped through the supposedly secured building; the explosion which is still ringing in my ears.

It feels as though the explosion is still in progress. Metal and concrete tear and whine against each other. The floor I’m lying on feels insecure; as though at any moment, it will give way. I’ve experienced earthquakes before, and this feels like an aftershock.

But it hasn’t been caused naturally. The still-sane part of me knows that. Us grunts

knew

this place was a Taliban hideaway before we set foot in here; they always look like this; a typically low-slung grey building which would be hard to pick out from the air on fly-bys, and easy to mistake for an agricultural building even if it was spotted. It’s the tyre tracks in the dust that really give these places away though, like they’ve been goddamn parking lots in a former life. There’d been reports of miscellaneous activity – training perhaps – radioed through to our unit. Whispers from the Comms Zone that large lorries were coming in the dead of night and loading up with suspiciously-shaped objects. But, as with all such reports, we always seemed too far behind the action. When we arrived there, all we expected to find was an abandoned building, the Taliban long gone.

The low-slung building was set in a gully about five or six clicks away from a small, dilapidated town which seemed to be pretty much carved out of the lunar landscape. We all asked ourselves how the hell the locals could stand it to live in a place like that. On arrival, we handed out the odd bit of scran to them, doing our humanitarian duty like good little boys before asking them about their friendly neighbours down in the gully. And, of course, we were met with that shifty-eyed look and sudden inability to speak English, despite the fact that seconds earlier, they’d been practically climbing up our packs, shouting ‘chocolate, chocolate’ or ‘water’.

It was always the same in Helmand – or Mayo as we called it, in homage to the most famous manufacturers of that particular foodstuff - always this uneasiness between us and the locals. Lots of the other grunts found it difficult to cope with situations like that, but I knew all about inward-looking towns and I knew all about how communicating with outsiders wasn’t so much frowned upon but a hanging offence. So I suppose that’s why the CO’s had my lads and I stay down in the town for a while, just to see whether I could find out anything else, while Sergeant Davis and his lot went down to the gully to act as the recon squad. Apparently there’d be some men from another regiment already there waiting for them waiting to fill them in on the latest intelligence on the site.

So there were five of us that remained in the town, and everywhere we went, we were followed at a safe distance by teems of small children. They looked so helpless that we had to keep reminding ourselves of how dangerous they actually were. Hell, some of the little bastards had probably been trained right up at the gully and had remained behind as some kind of intelligence operative or something.

Nothing moved in the town apart from our little Pied Piper procession. Most of the windows were boarded up, most of the vehicles looked to have been so overcome by dust and rubble of destroyed buildings that they’d never move again. It was like a version of one of those old American Wild West towns in the films where some bandit-group has come in and killed the sheriff and made off with the loot. We were stepping into the aftermath.

As our boots crunched across the loose gravel, we didn’t see many males over the age of about sixteen, but those we did – those wrinkled old specimens that sat mournfully on the roadsides – looked so immobile that they’d become a part of the landscape. And it may sound funny, but some of these men’s faces were so stained by war that they’d turned purple, or so it seemed in the harsh sunlight. Some of them practically

radiated

purple so that it seemed a kind of aura around their heads. Of course, I said nothing of my strange visions to any of my men. It doesn’t pay to sound like a glophead when you’re Lance Corporal in the Kingsmen; it’s the kind of thing that could end up as a permanent, if unspoken, destroyer of trust. And we were nothing if not a

tight

unit… So instead, we walked in silence – you get used to it here, you really do – and performed our hopeless task. Eventually, we were called up to the gully-building and we couldn’t get out of that dead end town fast enough.

We’re known as one of the most mobile of all of the infantry units, trained in dealing with the most demanding environments, but Mayo, Afghanistan, the heart of opium country sometimes asked us too much. Two of the younger grunts that I looked after were already struggling on our walk around town; now, in the open land where there was no shield from the blazing sun, they were starting to miss beats. I saw one of the lads – Selly from Preston – almost go down. Only his SA80, which he held in a trembling hand, stopped him from going over.

But I pushed them, despite the aching of my own legs. I pushed them because we were the Kingsmen, with over three hundred years of tradition behind us. I pushed them because Sergeant Davis would most likely complain if I took any longer than the time

he

thought necessary to cross the open land. Most of all I pushed them because it was part of me now, this machine-like intensity. And by pushing to the physical limits, I didn’t ever have to go to the mental limits. I didn’t have to think about why the hell I was in the arsehole of the world in the first place.

Occasionally, I did think, but only to vaguely wonder what the other men thought about when we trouped through the dustbowl. Were they, like me, staring off into the distance searching for single points of reference which were not tinted with the same sepia tones as everything else seemed to be; something that was not doused in the same dishwater brown-grey used in the credits of old episodes of

The Waltons.

What was Reynolds possibly thinking about? With his wiry frame and his dead-shot eyes he was destined to be a good soldier, but at only a year my junior, was he frustrated by his lack of progress up the chain of command? Was he plotting, cursing his luck or simply not thinking at all? And what about Smith, the young lad with the archetypal British name; a name which should have brought him the obvious nickname of Smit or Smitty, but who, because of his Chinese heritage was known as ‘28’ after the number of a dish on a takeaway menu? Was Smith disappointed or angry with his lot? He certainly never seemed to be. In fact he never seemed to be much of anything. Most of the time I wasn’t even sure if he ever listened to what anybody said. Certainly, he never made much of a response, save his oddly Mancunian grunt of ‘yessir’ or ‘can I have a snout?’

How about Delaney, the only one of us that was married with children; did he spend his time thinking about when he’d next see them again or did he block them out of his mind completely? I knew he carried their photographs around with him, but that was common. Some men were so determined to have

someone

back home that I suspected their photos were downloaded from websites or cut out from magazines. Delaney was known as Diva because he was always moaning; he even moaned about the nickname that had been dished out to him, which of course simply reinforced the fact that the rest of the grunts had chosen wisely.

And then there was Selly, the youngster that I’d had no bones about making my favourite. Did he realise how much he relied upon the rest of us? Did he realise that even as he walked, Reynolds and Smith often mocked him? Poor Selly reminded everyone of a puppy-dog. He had huge feet and hands which he looked as though he still needed to grow into properly; sandy hair which became mop-like when he didn't shave it. Selly had the most nicknames of anyone I knew. Reynolds liked to call him ‘Dulux’; Delaney liked to call him ‘Chubs’; Smith, when he could bring himself to speak to the big daft lump, referred to him as ‘Forrest’, as in Gump.

But bullying like this was par for the course and I let it go, even joined in if the mood took me. The powers-that-be in the forces actively encouraged it; it was their stock in trade to belittle the shit out of a man and then build him back up into the machine that they wanted him to be. That I’d actually been promoted in my time meant that I was already on the way to being half-Terminator.

To my left, Selly had started to whine again: ‘Why couldn’t they leave one of the Landies for us to take? Why do we always have to walk everywhere?’