Burial Rites (18 page)

Tóti squeezed Agnes’s hand. She looked at him, her expression inscrutable.

‘Do you think it’s my

fate

to be here?’

Tóti thought a moment. ‘We author our own fates.’

‘So it has nothing to do with God then?’

‘It’s beyond our knowing,’ Tóti said. He gently placed her hand back on the blanket. The feel of her cold skin unsettled him.

‘I am quite alone,’ Agnes said, almost matter-of-factly.

‘God is with you. I am here. Your parents are alive.’

Agnes shook her head. ‘They may as well be dead.’

Tóti cast a quick look at the women knitting. Lauga had snatched Steina’s half-finished sock from her lap and was ripping back the wool to amend an error.

‘Have you no loved one I might summon?’ he whispered to Agnes. ‘Someone from the old days?’

‘I have a half-brother, but only sweet Jesus knows what badstofa he’s darkening at the moment. A half-sister, too. Helga. She’s dead. A niece. Dead. Everyone’s dead.’

‘What about friends? Did any friends visit you at Stóra-Borg?’

Agnes smiled bitterly. ‘The only visitor at Stóra-Borg was Rósa Gudmundsdóttir of Vatnsendi. I don’t think she’d describe herself as my friend.’

‘Poet-Rósa.’

‘The one and only.’

‘They say she speaks in lines of verse.’

Agnes took a deep breath. ‘She came to me in Stóra-Borg with a poem.’

‘A gift?’

Agnes sat up and leant closer. ‘No, Reverend,’ she said plainly. ‘An accusation.’

‘What did she accuse you of?’

‘Of making her life meaningless.’ Agnes sniffed. ‘Amongst other things. It wasn’t her finest poem.’

‘She must have been upset.’

‘Rósa blamed me when Natan died.’

‘She loved Natan.’

Agnes stopped and glared at Tóti. ‘She was a married woman,’ she exclaimed, a tremor of anger in her voice. ‘He wasn’t hers to love!’

Tóti noticed the other women had stopped knitting. They were watching Agnes, her last sentence having carried loudly across the room. He rose to fetch the spare stool beside Kristín.

‘I’m afraid we’re disturbing you,’ he said to them.

‘Are you sure you don’t want to use the irons,’ Lauga asked nervously.

‘I think we are better off without them.’ He returned to Agnes’s side. ‘Perhaps we should speak of something else.’ He was anxious that she should remain calm in front of the Kornsá family.

‘Did they hear?’ she whispered.

‘Let’s talk about your past,’ Tóti suggested. ‘Tell me more about your half-siblings.’

‘I barely knew them. I was five when my brother was born, and nine when I heard about Helga. She died when I was twenty-one. I only saw her a few times.’

‘And you’re not close to your brother?’

‘We were separated when he was only one winter old.’

‘When your mother left you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you remember her from before then?’

‘She gave me a stone.’

Tóti shot her a questioning look.

‘To put under my tongue,’ Agnes explained. ‘It’s a superstition.’ She frowned. ‘Blöndal’s clerks took it.’

Tóti was aware of Kristín rising to light a few candles – the bad weather had made the room quite gloomy, and the day was rapidly dying. In front of him, he could only see the pale lengths of Agnes’s bare arms above the blankets. Her face was shadowed.

‘Do you think they will let me knit?’ whispered Agnes, inclining her head towards the women. ‘I would like to do something while I talk to you. I can’t stand being still.’

‘Margrét?’ Tóti called. ‘Have you any work for Agnes?’

Margrét paused, and then reached over and plucked Steina’s knitting from her hands. ‘Here,’ she said. ‘It’s full of holes. It wants unravelling.’ She ignored the look of embarrassment on Steina’s face.

‘I feel sorry for her,’ Agnes said, slowly pulling out lines of crimped wool.

‘Steina?’

‘She said she wants to get up a petition for me.’

Tóti was hesitant. He watched Agnes nimbly wind the loose wool into a ball, and said nothing.

‘Do you think it possible, Reverend Tóti? To organise an appeal to the King?’

‘I don’t know, Agnes.’

‘Would you ask Blöndal? He would listen to you, and Steina might speak to District Officer Jón.’

Tóti cleared his throat thinking of Blöndal’s patronising tones. ‘I promise to do what I can. Now, why don’t you talk to me.’

‘About my childhood again?’

‘If you will.’

‘Well,’ Agnes said, wriggling up higher on the bed so that she could knit more freely. ‘What shall I tell you?’

‘Tell me what you remember.’

‘You won’t find it of interest.’

‘Why do you think that?’

‘You’re a priest,’ Agnes said firmly.

‘I’d like to hear of your life,’ Tóti gently replied.

Agnes turned around to see if the women were listening. ‘I have told you that I have lived in most of the farms of this valley.’

‘Yes,’ Tóti agreed, nodding.

‘At first as a foster-child, then as a pauper.’

‘That’s a horrible pity.’

Agnes set her mouth in a hard line. ‘It’s common enough.’

‘To whom were you fostered?’

‘To a family that lived where we sit now. My foster-parents were called Inga and Björn, and they rented the Kornsá cottage back then. Until Inga died.’

‘And you were left to the parish?’

‘Yes,’ Agnes nodded. ‘It’s the way of things. Most good people are soon enough underground.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘There’s no need to be sorry, Reverend, unless of course you killed her.’ Agnes glanced at him, and Tóti noticed a brief smile flicker across her face. ‘I was eight when Inga died. Her body never took to the manufacture of children. Five babes died without drawing breath before my foster-brother was born. The seventh carried her to heaven.’

Agnes sniffed, and began to carefully thread back through the loose stitches. Tóti listened to the light clicking of the bone needles and cast a surreptitious look at Agnes’s hands, moving quickly about the wool. Her fingers were long and thin, and he was astounded at the speed with which they worked. He fought off an irrational desire to touch them.

‘Eight winters old,’ he repeated. ‘And do you remember her death very well?’

Agnes stopped knitting and looked around at the women again. They had fallen silent and were listening. ‘Do I remember?’ she repeated, a little louder. ‘I wish I could forget it.’ She unhooked her index finger from the thread of wool and brought it to her forehead. ‘In here,’ she said, ‘I can turn to that day as though it were a page in a book. It’s written so deeply upon my mind I can almost taste the ink.’

Agnes gazed straight at Tóti, her finger still against her forehead. He was unnerved by the glitter in her eyes, her bloody lip, and wondered if the news of Sigga’s appeal had, in fact, made her a little mad.

‘What happened?’ he asked.

CHAPTER SIX

IN THIS YEAR 1828, ON

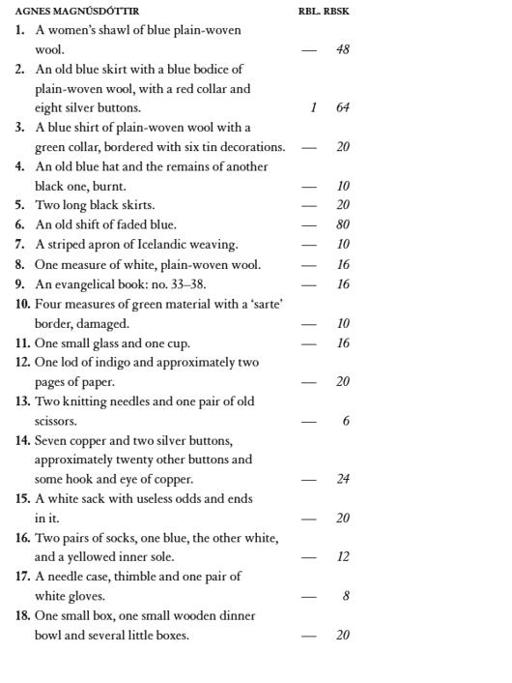

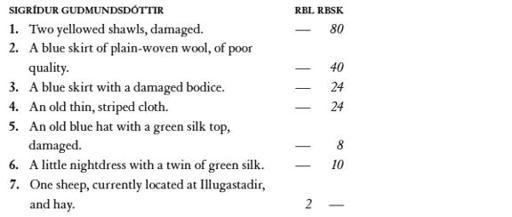

the 29th of March, we, the clerks stationed at Stapar at Vatnsnes – transcribing District Commissioner Blöndal’s oral description – write up the value of the possessions of prisoners Agnes Magnúsdóttir and Sigrídur Gudmundsdóttir, both workmaids at Illugastadir. The following assets, ascertained as belonging to the aforementioned individuals, have the following value:

We stamp and certify that the above assets comprise the total belongings of the aforementioned prisoners.

WITNESSED BY

:

J. Sigurdsson, G. Gudmundsson

THIS IS WHAT I TELL

the Reverend.

Death happened, and in the usual way that it happens, and yet, not like anything else at all.

It started with the northern lights. That winter was so cold that I woke every morning with a fine dust of ice on my blanket, from my breath freezing and falling as I slept. I was living at Kornsá then and had been for two or three years. Kjartan, my foster-brother, was three. I was only five years older.

One night the two of us were working in the badstofa with Inga. Back then I called her Mamma, because she was as much to me. She saw I had an aptitude for learning, and taught me as best she could. Her husband, Björn, I tried to call Pabbi also, but he didn’t like it. He didn’t like me reading or writing either, and was not averse to whipping the learning out of me if he caught me at it. Vulgar for a girl, he said. Inga was sly; she waited until he was asleep and then woke me, and then we would read the psalms together. She taught me the sagas. During

kvöldvaka

she’d tell them by heart, and when Björn fell asleep she’d make me recite the stories back to her. Björn never knew that his wife betrayed his orders for my sake, and I doubt he ever understood why his wife loved the sagas as she did. He humoured her saga stories with the air of a man humouring the unfathomable whim of a child. Who knows how they had come

to foster me. Perhaps they were kin of Mamma’s. More likely they needed an extra pair of hands.

This night Björn had gone outside to feed the cattle, and when he returned from tending them, he was in a good mood.

‘Look at you all, squinting by the lamp, when outside the sky is on fire.’ He was laughing. ‘Come see the lights,’ he said.

So I put my spinning aside and took Kjartan’s hand and led him outside. Mamma-Inga was in the family way, so she didn’t follow us, but waved us out and continued her embroidering. She was making me a new coverlet for my bed, but she never got to finish it, and to this day I don’t know what happened to it. I think perhaps Björn burnt it. He burnt a lot of her things, later.

But on this night, Kjartan and I stepped out into the chill air, our feet crunching the snow upon the ground, and we soon understood why Björn had summoned us. The whole sky was overrun with colour as I’d never seen it before. Great curtains of light moved as if blown by a wind, billowing above us. Björn was right – it looked as though the night sky was slowly burning. There were smears of violet that swelled against the darkness of the night and the stars that were littered across it. The lights ebbed, like waves, then were suddenly interrupted by new streaks of violent green that plunged through the sky as if falling from a great height.

‘Look, Agnes,’ my foster-father said, and he turned me by the shoulders so that I might see how the brilliance of the northern lights threw the mountain ridge into sharp relief. Despite the lateness of the hour I could see the familiar, crooked horizon.

‘See if you can’t touch them,’ Björn said then, and I dropped my shawl on the snow so that I could raise my arms to the sky.

‘You know what this means,’ Björn said. ‘This means there will be a storm. The northern lights always herald bad weather.’

At noon the following day the wind began to whip around the croft, stirring up the snow that had fallen overnight, and dashing it

against the dried skins we’d stretched across the windows to keep out the cold. It was a sinister sound – the wind hurling ice at our home.

Inga wasn’t feeling well that morning and had remained in bed, so I prepared our meal. I was in the kitchen, setting the kettle upon the hearth, when Björn came in from the storehouse.

‘Where is Inga?’ he asked me.

‘In the badstofa,’ I told him. I watched Björn take off his cap and shake the ice into the hearth. The water spat on the hot stones.

‘The fire’s too smoky,’ Björn said, frowning, then left me to my chore.

When I’d boiled some moss into porridge, I took it into the badstofa. It was quite dark in the room and, once I’d served Björn his meal, I ran to the storehouse to fetch some more oil for the lamp. The storehouse was near the door to the croft and as I approached it I could hear the wind howling, louder and louder, and I knew that a storm was fast approaching.

I’m not sure why I opened the door to look outside. I suppose I was curious. But some strange compulsion took me and I unlocked the latch to peek out at the weather.

It was an evil sight. Dark clouds bore down upon the mountain range and under their smoky-blackness, a grey swarm of snow swirled as far as you could see. The wind was fierce, and a great, icy gust of it suddenly blew against the door so hard that it knocked me off my feet. The candle on the corridor wall went out in an instant, and from within the croft Björn shouted what the Devil I thought I was doing, letting the blizzard into his home.