Burning Questions of Bingo Brown (15 page)

Read Burning Questions of Bingo Brown Online

Authors: Betsy Byars

Byars in 1983 in South Carolina with her Yellow Bird, the plane in which she got her pilot’s license.

Byars and her husband in their J-3 Cub, which they flew from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast in March 1987, just like the characters in Byars’s novel

Coast to Coast.

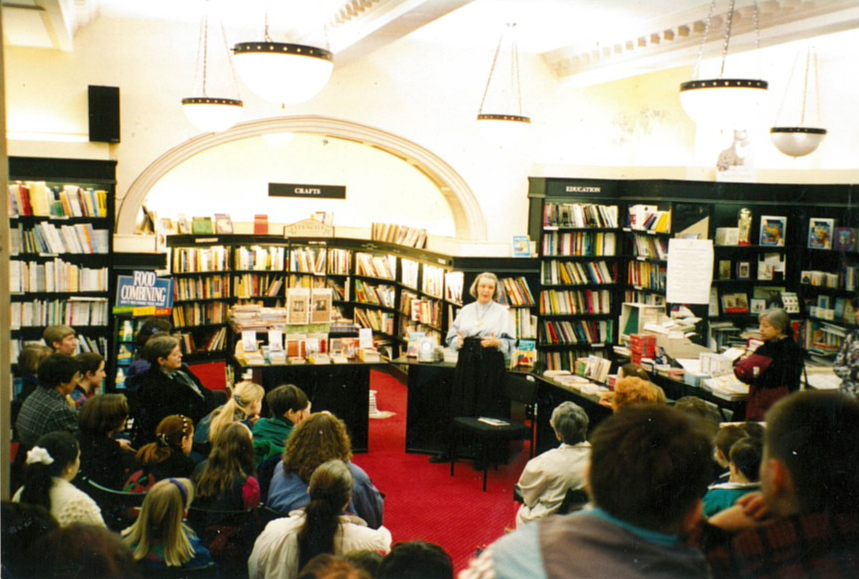

Byars speaking at Waterstone’s Booksellers in Newcastle, England, in the late 1990s.

Byars and Ed in front of their house in Seneca, South Carolina, where they have lived since the mid-1990s.

Turn the page to continue reading from the Bingo Brown Series

E

VERY TIME BINGO BROWN

smelled gingersnaps, he wanted to call Melissa long distance.

Actually, it was more of a burning desire than a want, Bingo decided. One minute ago he had been standing here, smiling at himself in the bathroom mirror, when without any warning he had caught a whiff of ginger. Now he had to call Melissa. Had to!

“Are you still admiring yourself?” his mom asked as she passed the door.

“Mom, come here a minute.”

His mom leaned in the doorway.

“Is that a mustache on my face or what?”

“Dirt.”

“Mom, you didn’t even look.”

“Do your lip like that.”

Obediently Bingo stretched his upper lip down over his teeth.

His mom said, “Ah, yes, I was right the first time—dirt.”

“Mom, it’s not dirt. It’s hair. There may be dirt on the hair but …” He leaned closer to the mirror. “I would be the first student in Roosevelt Middle School to have a mustache.”

“Supper!” his dad called from the kitchen. His dad was stir-frying tonight.

“A lot of women would be thrilled to have a son with a mustache,” Bingo said, “though I’ll have to shave before I go to high school. You aren’t allowed to have mustaches in high school.”

Bingo moved away from the mirror, still watching himself. “You can’t see it from here, but”—he stepped closer—“from right here, it’s definitely a premature mustache.”

“Bingo, supper’s ready.” His mother picked up a bill as she went through the living room.

Bingo followed quickly. “Hey, Dad,” he said. “Notice anything different about me?”

His father turned—he was holding the wok in both hands—but before he could spy the mustache, Bingo’s mom interrupted. “You will not believe the trouble I’m having with the telephone company.”

Bingo’s father said, “Oh?” He put down the wok and wiped his hands on his apron before taking the bill.

“Can you believe that? They’re trying to tell me that somebody in this family made fifty-four dollars and twenty-nine cents worth of calls to a place called Bixby, Oklahoma.”

Bingo gasped. He caught the door to keep from falling to his knees.

“Fifty-four dollars and twenty-nine cents! I told the phone company, ‘Nobody in this family knows anybody in the whole state of Oklahoma, much less Bixby.’ Bixby!”

Bingo said, “Mom—”

“The woman obviously did not believe me. Where does the telephone company get these idiots? I said to her, ‘Are you calling me a liar?’ She said, ‘Now, Madame—’”

Bingo said, “Mom—”

“Wait till I’m through talking to your father, Bingo.”

“This can’t wait,” Bingo said.

“Bingo, if it’s about your invisible mustache—”

“It’s n-not. I wish it were,” he said, stuttering a little.

Bingo’s mom sighed with impatience. Bingo knew that she got a lot of pleasure from a righteous battle with a big company and must hate his interruption. He hated it himself.

“So?” she said. “Be quick.”

Bingo cleared his throat. He walked into the room in the heavy-footed way he walked in his dreams. He clutched the back of his chair for support.

“Remember Melissa—that girl that used to be in my room at school?”

“Yes, Bingo, get on with it.”

“M-member I said she moved?” he was reverting back to the way he talked when he was a child.

“No, I don’t, but go on.”

“You have to remember! You and Dad drove me over to say good-bye! It was Grammy’s birthday!”

“Yes, I remember that she moved. What about it, Bingo? Get on with it.”

‘Well, she m-moved to Oklahoma.”

“Bixby, Oklahoma?”

Bingo nodded.

There was a long silence while his parents looked at him. The moment stretched like a rubber band. Before it snapped, Bingo cleared his throat to speak.

His mom beat him to it. “Are you telling me,” she said in a voice that chilled his bones, “that you made”—she whipped the bill from his father’s fingers and consulted it—“seven calls”—now she looked at him again—“for a total of”—eyes back to the bill—“fifty-four dollars and twenty-nine cents”—eyes back to him—“to this person in Bixby, Oklahoma?”

“She’s not a person! She’s Melissa! Anyway, Mom, you knew she had moved. I showed you the picture postcard she sent me.”

“I thought she’d moved across town.”

“She drew the postcard herself. I’ll get it and show it to you if you don’t believe me. It said ‘Greetings from Bixby, OK.’ Her address was there, and her phone number.

“As soon as I got the postcard, I went into the living room. You were sitting on the sofa, studying for your real estate license. I showed you the postcard and asked you if I could call Melissa.”

He was now clutching the back of the chair the way old people clutch walkers.

“My exact words were, ‘Would it be all right if I called Melissa?’ Your exact words were, ‘Yes, but don’t make a pest of yourself.’ That’s why the calls were so short, Mom. I didn’t want to make a pest of myself!”

His mother was still looking at the bill. “I cannot believe this. Fifty-four dollars and twenty-nine cents worth of calls to Bixby, Oklahoma.”

“I’m sorry, Mom. It was just a misunderstanding.”

“I’ll say.”

“I should have explained it was long distance.”

“I’ll say.”

Bingo’s father said, “Well, it’s done. Can we eat?” He glanced at the wok with a sigh. “Dinner’s probably ruined.”

“I don’t see how you can eat when we owe the phone company fifty-four dollars and twenty-nine cents,” Bingo’s mother said.

“I can always eat.”

“May I remind you that I have not actually gotten one single commission yet?”

“You may remind me. Now can we eat?”

In a sideways slip Bingo moved around the back of his chair and sat. He began to breathe again.

“Mom, can I ask one question?” Bingo asked, encouraged by the fact that his mother was sitting down, too.

“What?”

“Promise you won’t get mad.”

“I’m already furious. Just being mad would be a wonderful relief.”

“Well, promise you won’t get any madder.”

“What is the question, Bingo?”

“Can I make one more call to Melissa? Just one? You can take it out of my allowance.”

“What do you think?” she asked.

“Mom, it’s important. I need to tell her why I won’t be calling anymore.”

“Bingo, when you put fifty-four dollars and twenty-nine cents into my hand, then we’ll talk about telephone calls. Until then you are not to make any calls whatsoever. You are not to touch the telephone. Understood?”

“Understood.”

“Now eat.”

“I’m really not terribly hungry.”

“Eat anyway.”

Bingo helped himself to the stir-fry. The smell of ginger was overpowering now. It was coming from the wok! No wonder he was being driven mad. And if the mere scent of ginger had this effect on him—it was at the moment twining around his head, pulling him like a noose toward the phone—what would the taste do to him? Would he run helplessly to the phone? Would he dial? Would he cry hoarsely to Melissa of his passion while his parents looked on in disgust?

Bingo broke off. He had promised to give up burning questions for the summer, cold turkey, but how could he do that when questions blazed like meteors across the sky of his mind? When they—

“Eat!”

Bingo put a small piece of chicken into his mouth. The taste of ginger, fortunately, did not live up to its smell.

As he swallowed, he rubbed his fingers over his upper lip. The mustache—as he had known it would be—was gone. It had come out like the groundhog, seen its shadow in the glare of his mom’s anger, and done the sensible thing—made a U-turn and gone back underground.

After supper Bingo went to his room and pulled out his summer notebook. There were two headings in the notebook. One was “Trials of Today.” Under that, Bingo now listed:

1. Parental misunderstanding of a mere phone bill and, more importantly, their total disregard and concern for the depth of my feeling for Melissa.

2. Disappearance of a beloved mustache and the accompanying new sensation of manliness.

3. Breaking my vow to give up burning questions for the summer.

4. Tasting ginger, which, while it did not drive me as mad as I had feared, has left me with a bad case of indigestion.

The second heading was “Triumphs of Today.” Under that Bingo wrote only one word: none.

“D

EAR MELISSA,”

Bingo lay on his Smurf sheets. He had always been able to count on a peaceful night’s sleep on his Smurf sheets. But last Tuesday Billy Wentworth had come over, looked at his unmade bed, and smiled condescendingly at the Smurfs. After that, Bingo had not been easy on them.

Right now he was as uncomfortable as if he were lying on real Smurfs. However, he knew tonight was not a good time to ask his mother for more manly sheets.

He glanced at his letter and read what he had written.

“Dear Melissa,”

He retraced the comma and stared up at the ceiling.

Writing Melissa was not the same as calling her, because as soon as she heard his voice, she always said something like, “Oh, Bingo, it’s you! That’s exactly who I was hoping it would be.”

Her voice would actually change, get warmer somehow, deeper with pleasure. Girls were fortunate to have high voices so they could deepen them so effectively. His own voice got higher when he was pleased, which wasn’t a good effect at all.

If his mom only knew how it made a man feel to hear a girl’s voice deepen with pleasure. He knew there was no point in trying to explain that to his mom. His mom was in no mood to understand.