By the Rivers of Brooklyn (48 page)

Read By the Rivers of Brooklyn Online

Authors: Trudy Morgan-Cole

Tags: #FIC000000, #Fiction, #FIC014000, #General, #Newfoundland and Labrador, #Brooklyn (New York; N.Y.), #Literary, #FIC051000, #Immigrants

“No-one will ever know,” Valerie says mysteriously.

“Unless there's a note inside the box explaining,” Diane suggests.

As Claire runs her fingers over the suitcase, Anne remembers herself as a child, poking around in corners of Aunt Annie's house, looking for a trunk filled with old clothes and diaries, a box that would give her the key to her past. It's smaller than she had imagined it would be.

“Okay,” says Claire. “This is it. I'm taking the plunge.”

She flips up the rusty clasps of the suitcase. Inside, nestled in a water-stained red lining, are two smaller boxes. One is a shoebox, very battered, with a loop of string loosely tying it shut. The other is about the same size, but looks sturdier and more official.

Claire pulls the string off the shoebox and lays it on the coffee table. They all cluster around to see. On top is a card that says, “Get Well Soon.” Inside, the signature (

We're all praying for you, The Carter Family

) is crossed out in pencil. On the empty page opposite, another note is pencilled in a different hand. “That's my mother's handwriting,” Claire says. “I remember it. She used to send me cards and letters when I was little.” She reads aloud: “My dear daughter, just a few things for you to remember me by. God bless you, your Loving Mother.” Claire looks up. “Well, that was informative,” she says.

The few things are few indeed. There's a snapshot of a little girl. “That's me,” says Claire. A lurid calendar poster of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. A folded paper that turns out to be a ministerial license, granted to someone by the name of Rosamond Maranatha. A small pocket New Testament, well-worn with pages falling out and verses underlined in red pen. A cheap-looking pair of dangly earrings. Brown things that might be pressed flower petals, rose petals perhaps. A single yellowed baby sock. Claire holds the sock in her palm, staring at it. It's the last thing in the box.

All four women gaze at the tiny pile of memorabilia. Valerie reaches forward and picks up the Bible; Diane turns over one of the crisp flower petals and sniffs it.

“What's not there is a lot more striking than what is there,” says Valerie. And this is so true that for a moment no-one can think of anything else to say. A few things to remember me by. Remember who? Rose Evans? Rosamond Maranatha? Your Loving Mother?

“I don't know what to make of it,” Claire says. “Imagine this stuff, stuck away on a shelf all these years, and him finding us tonight. What a coincidence.”

“What's in the other box?” Diane says.

They have all been so taken with the contents of the shoebox that no-one has spared a thought for the second box, which is much heavier. When opened, it is found to contain a wooden vase or jar with a sealed lid, about ten inches high and quite heavy. Everyone stares at it.

“It's an urn,” Valerie says finally. “It must be your mother'sâ”

“Ashes,” Anne says.

“Remains,” says Diane at the same moment.

“Actually, the word they use now is

cremains

,” Valerie says.

Claire is still staring at the urn. Finally she says, “My mother left instructions to have herâ¦her ashesâ¦packed up and sent to me, and then left them with someone who forgot all about them. She's been sitting on a shelf for heaven knows how long.”

“Maybe since 1977,” Anne suggests. “That death certificateâ¦Rose Evans, the minister? It could have been her.”

“Sweet land of Goshen,” Claire says. “What am I supposed to do with these?” She makes a move as if to unscrew the lid, then stops and lays the urn down on the coffee table. “Take them home and bury them, I guess. I suppose that's what she wanted, to be buried back home. Otherwise, why send it to me?”

“You could scatter them,” Valerie suggests.

“Where?” Claire says. “It makes more sense to bury them.”

“I wonder if she really belongs back home,” Diane muses, picking up the urn and turning it in her hands. “Cheap finish. I guess this was all she could afford. I mean, she lived most of her life here, in Brooklyn, or so it would seem. Wouldn't she want to be scattered, or buried or whatever, right here?”

“Well, she's

been

right here for nearly thirty years,” Anne points out, and tries to suppress a giggle. But it's contagious. Diane laughs her loud, unfettered laugh, and Valerie joins in. Then Claire is laughing too, all four women laughing so hard that tears stream down their faces.

“Just think, Anne,” Claire says. “All these years I've been coming to New York trying to find my mother. And all the while she was in the back of someone's closet in Crown Heights!”

The laughter passes after awhile, leaving them all weak. “I think you should scatter them off the Brooklyn Bridge, or the Staten Island ferry,” Valerie says.

“What a tacky idea, Val,” Claire says. “It's the kind of thing people do in books, not in real life. And I think it might be illegal. You need a permit or something, don't you? The sensible thing to do is to take her home and put her in the family plot, with Nan and Pop and Annie and Bill. I wouldn't even know how to go about scattering someone.”

“Me either. All our people were always buried,” Diane says.

“Oh, I've done it,” Valerie assures them. “A dear, dear friend of mine, three or four years ago, passed away. Tom Sutton, a lovely gay man, died of AIDS, sadly. A group of us went to his garden and scattered his ashes at night, by candlelight. A beautiful ceremony. We had a piper, too. I like the idea of doing it over water.”

“Someone does that in a book. Off the Staten Island ferry, or maybe between Brooklyn and Manhattan,” Anne recalls suddenly, and looks to Valerie for confirmation. “Remember? Is it in

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

?”

“No, but you're right, I remember the scene,” Valerie says. “Not

A Tree

Grows in Brooklyn

, but something like that. It's not the way you'd think it is,” she adds. “Not like fireplace ashes or cigarette ash. They're very gritty, and they cling to your fingers. As if the dead don't want to let go.”

Claire looks up from the urn to Valerie. “I don't think letting go was anything my mother ever had a problem with,” she says.

Valerie is in town for one more day, so they agree to get together the next afternoon and do some sightseeing. “No ashes, no cremains,” Claire warns. “But maybe we could take a bus tour, or walk across the Brooklyn Bridge. I've never done that.”

“Neither have I,” says Valerie.

So the next day they take the subway to Battery Park, where you can get on the trolley tour of Brooklyn. Anne brings Hannah and an umbrella stroller; Diane brings her husband Mike, who Anne always thinks is strikingly handsome for a man in his seventies, with snow-white hair over a strong-boned face with vivid green eyes. He takes Hannah on his lap as soon as they're settled on the trolley. “How's my little angel?” he asks Hannah.

“I'm not an angel, I'm a princess. A

ballerina

princess,” Hannah informs him solemnly.

“God, she's a doll,” says Diane.

Valerie, who has never seen Hannah before, says, “What a shame Annie never lived to see her.”

“Yes, she would have loved to,” Anne says, swallowing down the lump that quickly rises in her throat. Aunt Annie outlived all her siblings, dying at ninety-two in her own house on Freshwater Road. She was proud of Anne and got cable TV just so she could see her girl on the American news, even though she always worried when Anne was reporting from those dangerous places where the bombs were. She would have loved to see Anne settled down with a little girl, but nobody lives long enough to see everything, Anne thinks.

The trolley tour guide makes a number of jokes, none of which are funny, and tells them the wrong date for the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge as they drive over it. When the trolley stops at the Marriott hotel he tells them they can get off to walk across the bridge if they want, and catch another trolley later to continue the tour. They climb off, a large and awkward crew. The trolley ride has made Hannah drowsy and she is draped over Anne's shoulders like a very heavy scarf while Mike opens the umbrella stroller. The three older women all have extra-large purses and Valerie has shopping bags as well. When Hannah is buckled into the stroller with the sunshade pulled down, they begin their slow trek across the bridge. The day is warm and golden, sunshine spilling down on them. Claire, Valerie and Diane all wear hats.

Many people are walking on the bridge today. Traffic roars beneath them, so noisy they can't even talk to each other. Mike stops to read each of the informative historical plaques, but the women wander ahead, finally finding a place to lean on the railings and look out at the river. It's sluggish and slow-moving, with a few boats lazily ploughing their way through. “They say once upon a time it used to be filled with boats from one bank to the other,” Valerie shouts.

“They say that about St. John's harbour too,” Claire yells back.

Different times, Anne thinks. The river seems almost irrelevant now, just a backdrop for the real current of humanity that rages back and forth over the bridge.

Claire reaches into her carry-all. “Guess what I brought?” she shouts, pulling the urn out of the bag.

Valerie looks so excited she actually claps her hands. Anne is shocked. Once Claire has said a course of action is foolish, tacky, and possibly illegal, that's generally the final word on the subject.

“You're going to scatter them from here?” Val shouts.

“I thought maybe just a few! Bring the rest home to bury! But I still think it might be illegal!” Claire yells, turning from one to the other. She looks uncertain, and seeks out Anne's face first. “What do you think I should do? Is this the right thing?”

In thirty-eight years, Anne cannot recall her mother ever asking this question â of her, or of anyone else. She feels a huge wave of love for Claire, so certain, so brittle. She moves to put an arm around her mother's thin shoulders and speaks right in her ear. “I think if you want to do it, then it's the right thing,” she says.

Diane and Valerie nod vigorous agreement. Mike is some distance away, immersed in reading a plaque. The four Evans women â five if you count the one asleep in her stroller, six if you count the one in the urn â are alone together on the Brooklyn Bridge. Claire takes the top off the jar and looks around quickly, perhaps for the Cremain Police.

“Go ahead!” shouts Diane.

Claire tips the jar. Nothing comes out, and she tips it a little more, then reaches up with her fingers to hook the ashes loose. A light drift of grey, gritty stuff falls out and is caught by the breeze, swirling down to the water.

“Not like they're going to notice a few more bits of dirt in the East River,” Diane says in Anne's ear.

“Here.” Claire hands Anne the urn. “You do some. But save some for home!”

Anne takes the urn, hoping it doesn't slip from her hands and fall into the water below. Her hand shakes a little as she jiggles the urn, dislodging a few more particles of her unknown grandmother who crossed this river so long ago, leaving behind one life to find another. The grey swirl drifts down and they all watch eagerly till it is invisible. Anne tilts the jar back upright, making sure to save some to go home.

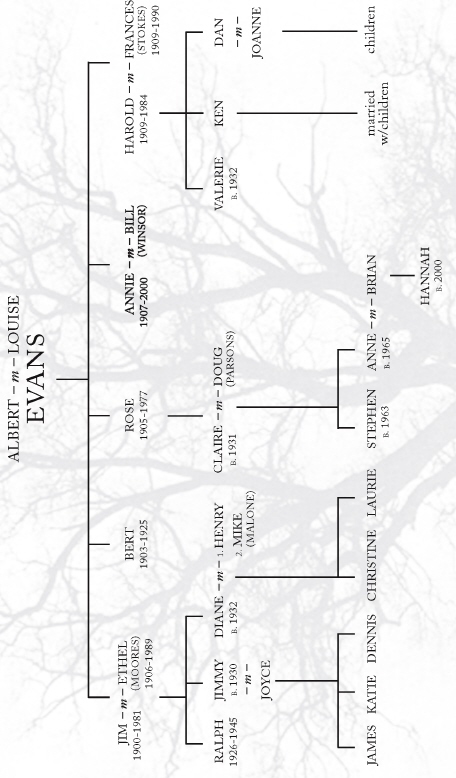

EVANS FAMILY TREE

I

AM VERY GRATEFUL

for financial assistance from the Newfoundland and Labrador Arts Council and from the City of St. John's for grants which allowed me to research and write this book.

Support and critique are essential to the writing process. I have been very fortunate to be a member of the Newfoundland Writers' Guild, whose members have listened to and critiqued portions of this novel at workshops over a period of several years. Likewise, I owe an eternal debt of gratitude to the Strident Women for loving and reliable cheerleading, hand-holding, butt-kicking and coffee-drinking as required.