Canada Under Attack (2 page)

When the men prepared to strike out in the brittle cold of a Montreal spring day the excitement was palpable. In addition to a handful of regular soldiers, de Troyes had recruited 70 voyageurs, a hardened, independent group of fur traders known for their ability to survive under almost any conditions. Included in the expedition were two wealthy seigneurs and a priest, who watched as they began to assemble the sleds, canoes, and arms necessary for their journey. On March 30, the expedition set off on foot over the still frozen Lake of Two Mountains. Between them, the men carried their own heavy packs, guns, ammunition, and the eight 100 pound birch bark canoes they intended to use when the ice finally melted. The few sleds pulled by teams of oxen had been commandeered by the noblemen and the expedition's officers and were used to carry their luggage and personal effects. As they slowly made their way across the lake, the ice suddenly broke and a sled holding most of the Seigneur St. Germain's luggage almost plunged into the lake. The men were barely able to rescue the oxen, several of which did fall through the ice. A frustrated de Troyes ordered all of the oxen be sent back. The next day it was the men themselves who continually broke through the ice. The progress of the entire expedition paused as their fellow travellers dropped to their bellies and inched along the ice to attempt a rescue. De Troyes was out in front, leading them onward toward the Ottawa River, using his sword to test the thickness of the ice. Conditions worsened when a spring storm found them, pounding the river with heavy rain and high winds, and turning the frozen waters into dangerous slush.

After a brief stay on an island, which did little to warm their bodies or their spirits, the tiny army pushed on. On April 9, an advance party rushed back with the news that the Long Sault Rapids were just ahead and the best option was to drag their canoes up the rapids through the waist deep, ice-choked water. Some of the men, including de Troyes and the priest, Father Sfivy, opted for a route that took them along the craggy shoreline. But that difficult path severely damaged several of the canoes. They continued their assault on the rapids over the next five days. By then the undisciplined, rambunctious voyageurs had had enough. A fight broke out, fuelled by alcohol and exhaustion. One of the men had his jaw broken with the butt of a rifle. Once the officers had broken up the fight and settled the men, de Troyes called out the worst offenders, took their “eau de vie” away, and made them carry a sack of corn in its place. De Troyes, a career soldier, frequently despaired at his men's lack of discipline. By the end of the journey he would have even more to despair.

In the days following the fight, several voyageurs decided to help themselves to a cache of moose skins that had been hidden by one of the Native tribes that frequented the area. When the men returned with their loot, de Troyes promptly forced them to put it back. On April 14, Father Sfivy held high mass. Afterwards de Troyes divided the men into three brigades, providing each brigade with separate marching orders. He also implemented nightly guard duty in the hopes of in stilling some semblance of discipline in the men, “which alone,” he lamented, “is lacking in the natural worth of Canadians.”

1

Discipline would remain a problem but de Troyes was nothing if not creative in dealing with problems. One unfortunate soul was tied to a tree for the duration of an encampment. Desertion also became a problem as the men suffered through the horrifying conditions. One by one they disappeared into the dense bush, never to be seen again. On April 30, four men deserted, taking one of the now precious canoes with them.

After that, progress was depressingly slow. Occasionally the men found themselves neck deep in water, their canoes held high over their heads, as they attempted to drag themselves through the rapids. Disgusted, a few of the voyageurs attempted to pole their way up the rapids only to wreck their canoes. On some days they managed to cover just eight kilometres in over 12 hours of travel. The rough conditions, boredom, and cold frequently caused serious illness and accidents. Burns were common. One man chopped a finger off while attempting to collect firewood. A keg of gunpowder exploded as the men celebrated May Day. Fortunately, no one was killed or injured. At the end of May the entire invasion almost came to an abrupt end when a forest fire, touched off by a campfire, roared down a hill toward them during a portage.

In May the force arrived at Lake Abitibi. De Troyes called a halt in order to build a replica of an English fort so that his men could practise capturing it. By June 8 he deemed the men ready to move on. But two days later one of his best soldiers, a man who had come the entire distance without being able to swim, drowned when the canoe he was travelling in tipped over while running a rapid. D'Iberville â who was travelling in the same canoe â survived, but lost most of his possessions. By then they were very near Moose Fort, de Troyes' first objective. There was barely time to bury the soldier and no time to mourn him. De Troyes immediately sent D'Iberville and several others ahead to scout the fort. Finally, at dawn on June 21, they attacked.

Moose Factory Fort.

England and France were not at war and relations with the local Natives were mutually profitable; the English had no reason to suspect an attack might be imminent. The 17 inhabitants of Moose Fort were still asleep when the French attacked, but they quickly rallied.

D'Iberville raced ahead of his men and made it through the gate just before the English managed to swing it closed. He was left stranded inside while his men outside tried to break down the gate and come to his rescue. D'Iberville managed to hold off the English soldiers for several long minutes before his men finally breached the fort. Within half an hour the English fur traders had surrendered, some still in their nightshirts.

Three days later, the French attacked Fort Charles. The

Craven

, a Hudson's Bay Company ship, was moored on the bay, just outside the fort. De Troyes dispatched D'Iberville and a handful of men to take the ship while he and the remaining men surrounded the fort.

D'Iberville and his men rowed over to the ship and stole onto it, quickly overpowering the unsuspecting sailors on board. On the shore, de Troyes easily took the fort and commandeered D'Iberville's newly conquered ship to hold the loot he had gathered from the conquered forts.

On July 9, de Troyes attempted to return to Moose Fort, but became lost in the fog and did not find his way back for another week.

De Troyes then set his sights on Fort Albany. While the French bombarded the fort with canon borrowed from Moose Fort, D'Iberville witnessed a terrified woman running right into the path of an explosion. He and Father Sfivy dashed forward and, candle in hand, went from room to room looking for her. They finally found her, badly injured, lying on the floor in one of the rooms. D'Iberville reportedly carried her to a couch and called for a surgeon, then stayed with her while she was tended to, refusing entry to everyone else.

By the end of August, de Troyes was ready to return to Quebec. After naming D'Iberville as governor of the forts and assigning him 40 men to hold them, de Troyes headed back to Quebec to celebrate his victories. D'Iberville and his men survived the winter of 1686 before returning to Quebec in the summer of 1687, when no supplies arrived for their relief.

The forts that de Troyes and D'Iberville had worked so hard to secure were not to remain in French hands for long. By 1693, the British had retaken Fort Albany and the Hudson's Bay Company re-established the other forts by 1713.

After a brief return to France, D'Iberville returned to James Bay in the summer of 1688. As D'Iberville busied himself filling his holds with furs he was unaware that the English were planning to retake Fort Albany. As D'Iberville's ship tried to sail out of the mouth of the Albany River into James Bay, two English ships arrived to blockade him. The standoff lasted throughout the winter â while the English and French stared one another down the temperature dropped and all three ships became trapped in the ice. English on the Albany River. When the English requested a truce in order to hunt for fresh game he denied them. Because they lacked adequate supplies the English crew starting showing signs of scurvy. When D'Iberville heard that the English were falling ill he sent word that he would allow the English surgeon to hunt. When the unfortunate surgeon ventured out, D'Iberville promptly arrested him. Although no shots were exchanged, several of the English died of scurvy, cold, and other diseases. Eventually the English were forced to surrender. D'Iberville took his ship back to Quebec full of furs and English prisoners.

D'Iberville was equally capable of compassion, honour, and unspeakable cruelty. It was his cruelty that won him infamy during his confrontation with the

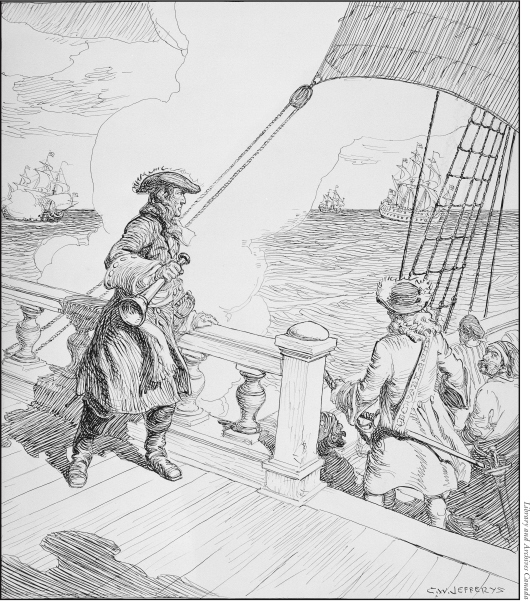

D'Iberville's Defeat of the English Ships in Hudson Bay, 1697.

For the next 10 years the English and the French would jockey for position in Hudson and James Bays, with first one and then the other seizing control. More often than not, D'Iberville was at the forefront of the French efforts. But he was seldom able to hold onto what he took and 10 years of warring in Canada's frozen north had wearied him.

D'Iberville was ready for a new challenge. He found it on the Atlantic coast, where the French and English were engaged in a battle for control of both the fur trade and rich stocks of fish. For more than a century, English and French fishing boats had operated in the waters off Newfoundland. Various settlements were founded by both countries, but they were isolated, sparsely populated outposts. They had little to do with one another and rarely came into contact, let along conflict, with one another. The populations of these outposts were extremely hardy people who had little experience with war. There were a few soldiers garrisoned in the far reaches of Newfoundland, but there did not seem to be much reason for them to be there. However, by the middle of the 17th century the English had greatly increased their presence in the waters southeast of Newfoundland. The area became known as the English Shores.

The French fishermen were unimpressed. Renewed interest in the fur trade, privateers who preyed on boats from both countries and rivalries from a far-off continent aggravated the tension between the colonies. The French heard that the English fishermen were making a fortune selling their salted cod to Spain and Portugal. They also knew that the English settlements, like Ferryland on the southern shore of the Avalon Peninsula, were isolated, sparse, and lacked basic defensive works. They would make easy targets. France called upon D'Iberville, fresh from his successes at Fort Henry, to drive the English from the shores of Newfoundland once and for all.

The French government wanted to have sole control of the region and gave D'Iberville the task of eliminating the English presence there. For his first target he chose Fort William Henry, along the Acadia-Maine border, close to present-day Bristol, Maine. The fort was easily taken and D'Iberville moved north. He arrived in the French capital of Placentia, Newfoundland, at the end of August 1696. In Placentia, D'Iberville clashed with the governor, Jacques-François de Monbeton de Brouillan, who, as the civilian representative of the Government of France, had ultimate command over the mission. De Brouillan had a reputation as a strong governor who had successfully defended his colony from repeated English attacks, but he was also a rapacious man who maintained a monopoly over trade and was rumoured to have forced his soldiers to take up fishing and then demanded a share of their profits. The Canadians and the Natives made things difficult for De Brouillan, refusing to follow anyone but D'Iberville, who, annoyed and frustrated by the conflict with De Brouillan, was threatening to return to France.

2

As a compromise, and likely to keep the two conflicting parties separated, France settled on a two-pronged attack led separately by both men. It was agreed that the governor would invade St. John's by sea and D'Iberville would take the more difficult land route to attack Ferryland. On November 1, D'Iberville and his men began to walk across frozen Placentia Bay. Nine days later, two of which were spent without provisions, they reached Ferryland. The journey was an arduous one; the Abbé Jean Baudoin recorded that, “We have walked nine days, sometimes in woods so thick that you could hardly get through, sometimes in a mossy country by rivers and lakes, often enough up to your belt in water.”

3