Canada Under Attack (5 page)

There was a solution, but the French commanders did not seem to see it. The colonial flanks were clearly exposed and unprotected. The French just had to send out troops to attack the isolated batteries, but the commanders feared the tenuous hold they had on their men after the recent mutiny. The habitant lamented that the commanders did not dare send out their troops to challenge the English for fear that the unhappy, recent mutineers might join the enemy.

9

The New Englanders had problems of their own. The eager, inexperienced gunners would frequently overload their canons, causing fatal explosions. Insubordination was also rampant, as was drunkenness. The men frequently ignored orders and alcohol inhibited their ability to fight and occasionally resulted in their not showing up to the fight at all.

Warren and the British Navy hovered just outside the harbour, held back by the guns of the Island Battery. They were eager to join the fight and Warren constantly pressed Pepperell to take action against the battery. But while the colonials were able to secure the lighthouse, the battery remained defiant. The first four plans to attack were abandoned. On the first actual try, most of the 800 colonial soldiers came to the battle drunk and the officer in charge of the operation failed to show up at all. In a second attempt, the colonials crept up to the battery under cover of the area's notorious fog. Once one third of the men had reached the beach undetected, a few inebriated soldiers called out three cheers for their success. The French immediately opened fire and for the next several hours, chaos reigned.

When the smoke and fog finally cleared, over 60 colonials lay dead and several hundred had been taken prisoner. The Island Battery still belonged to the French.

Warren still pressed to join the fight and Pepperell knew that success in Louisbourg depended upon his capture of the Island Battery. A second attempt was merely a matter of time and careful planning. Pepperell salvaged a number of heavy guns that had been sunk by the French just beyond the lighthouse and ordered his men to construct a battery near the lighthouse to house them. The lighthouse offered an unmistakeable advantage â its elevation was much higher than that of the Island Battery and, once completed, the salvaged guns could be pointed directly into the small fort. They completed work on the fort on June 10, and almost immediately opened fire on the Island Battery. For two days they kept up a steady barrage that ended with many of the French fleeing into the surf and taking their chances swimming to the fortress. By nightfall on the twelfth, the Island Battery was in colonial hands. Almost immediately the British sailed into the harbour eager to join the fight.

The citizens of Louisbourg had seen enough. Their soldiers were exhausted, as was their supply of gunpowder. Within days the Circular Battery had been reduced to ruins and the west wall completely destroyed. The colonials were in control of the West Battery itself and had turned its terrifying guns down into the city they had been designed to protect. The British were massing their fleet in front of the city. The citizens petitioned the government to end the siege. After 45 days of relentless shelling, the siege was finally lifted. The acting governor, Duchambon, initiated a surrender in which the French would be allowed to march out in their colours and the citizens within Louisbourg would be granted safe passage to France along with all of their property.

The colonial soldiers, many of whom had joined in hopes of reward, were angry that the loot they had hoped for would be denied to them. They would be angrier still when they finally realized the consequences of “the Greatest conquest, that Ever was Gain'd by New England.”

10

But in the meantime, cities in both the colonies and Great Britain celebrated the victory over Louisbourg with speeches, picnics, and fireworks. In London, the Tower guns were set off and more fireworks illuminated the skies. Warren, Pepperell, and Governor Shirley all gained tremendous rewards and accolades. Warren was made a rear admiral, Pepperell received a baronetcy, and Shirley received the lucrative right to raise regiments. But not everyone found their riches in the invasion. William Vaughn, the erstwhile captain who had so buoyed the invasion with his taking of the Royal Battery, travelled to London hoping for reward. He received no recognition and instead contracted smallpox and died in the winter of 1746. The rest of the men received no riches and only the momentary gratitude of their fellow New Englanders. Two thousand of them also received notice that they were expected to continue their occupation of Louisbourg until they could be relieved by a force on its way from Gibraltar. The force failed to arrive. Pepperell wrote to his wife,

We have not as yet any answer to our express's from England, and it being uncertain whether I shall return this winter, although it is the earnest desire of my soul to be with you and my dear family, I desire to be made willing to submit to him that rules and governs all things well; as to leave this place without liberty. I don't think I can on any account.

11

Conditions within the fort were nothing short of brutal. The men lived in squalid, filthy conditions in the ruins of the fort. The sickness that had plagued the troops over the cool, wet summer worsened as the weather got colder. Once winter had closed the fort off from any new provisions or relief the sickness worsened.

Between November and January, 561 English soldiers were buried at Louisbourg, many beneath the floorboards when the ground became too frozen for the survivors to dig graves.

12

That number is staggering compared to the total loss of 130 men during the siege: 100 to gunfire and another 30 to disease. By February, Pepperell commanded just 1,000 able-bodied men; the other 1,000 had been felled by sickness or death. The British governor wrote of his time in Louisbourg, “I have struggled hard to weather the winter, which I've done thank God, tho was not above three times out of my room for five months ⦠I am convinced I shou'd not live out another winter in Louisbourg.”

13

To further compound their troubles, the men received minimal pay and found their protests falling on deaf ears. In one dramatic episode, a group of New Englanders marched to the parade ground without their officers and tossed their weapons down. A British Navy officer, who had witnessed both the conditions at Louisbourg and the protest, remarked that he had always thought the New England men to be cowards but he thought that if they had a pickaxe and a spade they would dig their way to hell and storm it.

14

In March the promised relief finally arrived and the surviving colonists were allowed to return to their families. A small group of them took a souvenir with them: a large iron cross from the cathedral at Louisbourg. Eventually finding its way to Harvard, the Louisbourg Cross remained at the university for nearly 250 years until they finally agreed to permanently loan it to Canada in 1995.

But in 1746 the battle was still going on, at least in the eyes of the French. On the heels of the British reinforcements a flotilla of French warships had also headed toward Gabarus Bay, intent on retaking the fort and redressing the humiliations suffered at Louisbourg. But luck and weather once again favoured the English colonists. The French fleet was plagued by illness, beset by storms, and harried by the English Navy until it finally gave up and abandoned its mission to retake Louisbourg. The English who were in command of the fort were elated, but their joy soon turned to disgust when news reached them that during the negotiations of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle the British had traded Louisbourg back to the French in return for the small fort of Madras in India. Everything the colonists had fought for had been abandoned; the French commanded the mighty fort of Louisbourg once more.

The French were not able to enjoy the fort for long. By 1757 they were back at war with the British, and both the Americans and the British had once again set their sights on Louisbourg. They started slow; first isolating Louisbourg by confining the first fleet of reinforcements sent to the city and then by defeating a second fleet sent out to rescue the first. A third fleet finally made its way to the island but its commander, worried about a possible invasion, decided to lead his ships to the relative safety of Quebec. His concerns were justified. The French had made some important improvements to the fortress. They were no longer exposed along the swampy east; instead they were protected by lines of guns and trenches, fronted by a further defence called an

abatis

, felled trees that were sharpened and pointed towards the advancing enemy. Despite the French having strengthened the fortress it was still a tempting target because it controlled access to Quebec and the rest of French Canada.

With Quebec City as the final target, the British planned two major campaigns. The first, involving over 15,000 men, was launched against Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, while Major-General Jeffrey Amherst led a 12,000 man force toward Louisbourg. Among the officers that Amherst selected to launch the attack on Louisbourg was a young James Wolfe, who would go on to lead the invasion of Quebec City and end French hegemony in North America forever. While the British locked down all of the ports from Nova Scotia to South Carolina, in order to keep the invasion secret, Amherst gathered his troops in the newly built Fort George in Halifax. Within weeks they were joined by nearly 14,000 sailors and marines. Within Louisbourg, a force of barely 7,500, and 4,000 civilians, waited nervously for the inevitable invasion.

15

As dawn broke on June 1, 1758, the shocked Louisbourg sentries finally spotted the first sails of the massive invasion force anchored in Gabarus Bay. Rough seas kept them at anchor but the swells calmed and in the early hours of June 8 the entire fleet doused their lights while 2,000 soldiers slipped into the small bateaux that would carry them to shore. They bobbed in the water, waiting for the signal that would launch a three-pronged attack on three French beaches.

At 4:00 a.m., the ships began to fire on Louisbourg and the fortress answered with the steady beat of drums sounding the

générale

â the call to arms. Most of the French forces turned a steady, terrifying barrage against the tiny boats. Several boats overturned and the soldiers, weighted down by their heavy uniforms and packs, sank to the bottom of the bay. As a horrified solider looked on, “One boat in which were Twenty Grenadiers and an officer was stove, and Every one Drowned.”

16

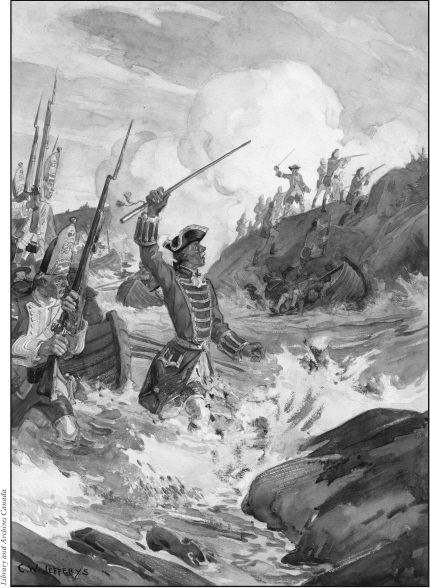

Standing at the bow of his boat, his red cape flapping in the wind, General Wolfe made a tempting target. But the French held their fire until the boats were well within musket range, and then let loose a furious barrage that left Wolfe desperately waving the accompanying boats back with his cane. They attempted to turn around amidst heavy fire from the French and rough waves that pushed them back toward the shore.

It seemed that the massive invasion, so carefully planned, was going to end in unmitigated disaster. But then, as occasionally happens in war, fate intervened and saved the day for the British and colonials. Officers aboard three of the boats spied a rocky outcropping beyond the range of the French guns and turned toward it. Wolfe immediately ordered the ships nearest him to follow and they pulled their boats onto shore beyond the view of the French. The French Governor Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour was stunned to learn that the British and Americans had made land. Instead of launching a counterattack, he elected to pull back. He ordered the Royal Battery destroyed and abandoned. A day later he ordered the Lighthouse Battery destroyed and then withdrew his men into the fortress.

Wolfe Walking Ashore Through the Surf at Louisbourg.

Wolfe barely missed a beat. He marched his almost 2,000 strong army around the bay with an eye to taking and rebuilding both the Lighthouse and Royal Batteries so that they could be used against Louisbourg. In the meantime, Amherst kept his own army busy building a road through the sand, bog, and marsh in preparation for an attack by land. In a replay of the 1745 attack, hundreds of men were put to work pulling the massive guns into position. On June 18, the soldiers were startled to hear the sounds of a naval battle occurring within Gabarus Bay. They did not know it then, but de Drucour had attempted to smuggle his wife and several other women out of Louisbourg to the safety of Quebec. Madame de Drucour and her companions were taken from the defeated French ship and returned with honour and consideration to her husband at Louisbourg. Despite the courtesy of the British, for the remainder of the siege Madame de Drucour climbed the fortress ramparts daily to fire three canon shots in honour of the king of France. Amherst was so impressed with the lady's courage that he sent her a letter and a gift of two pineapples with several messages and letters from captured Frenchmen. Another flag of truce appeared and a basket of wine was delivered to Amherst with the compliments of the governor and his wife. As soon as the wine was delivered the canons roared to life on both sides. Courtesy and compliments aside, there was still a war to be won.