Candyfloss (10 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

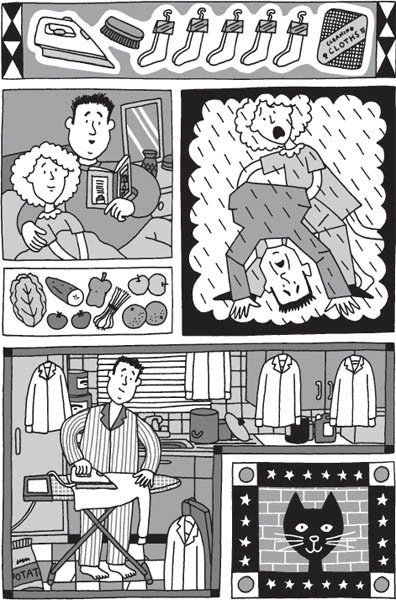

I hadn’t properly unpacked my pink pull-along case or my cardboard boxes of clothes. My school blouses were horribly screwed up and my skirt was creased so much it looked as if it was pleated.

‘Dad, can you iron these?’ I said.

‘What? Oh God, I’m not sure my old iron works any more. I don’t really bother with my stuff, I just drip them dry.’

I had to go to school all crumpled. I couldn’t find my good white socks so I had to wear an old pair of navy woolly winter ones, and my trainers were all muddy from the garden. I couldn’t even get my hair to go right. I’d been tossing and turning all through the night and now all my curls stuck straight up in the air as if I was plugged into an electric socket.

Dad didn’t seem to notice as he drove me to school. We arrived at the exact time Rhiannon was jumping out of her mum’s Range Rover.

They

noticed.

‘Floss! Oh dear!’ said Rhiannon’s mum. ‘You look a bit bedraggled, darling.’

‘I’m fine,’ I said.

‘Why have you got those funny socks on? Like,

navy

?’

said Rhiannon. ‘And yuck, what’s that on your

shoes

? It’s not dog poo, is it?’

‘No, it’s just a bit of mud,’ I said, blushing.

Dad was peering out of the van anxiously, biting his lip. He frowned as Rhiannon’s mum leaped out of her Range Rover and went over to him.

‘Look, Mr Barnes, I know it’s difficult for you now you’re a one-parent family—’

‘Flossie’s got two parents,’ said Dad. ‘I’m simply the one currently in charge.’

‘Whatever. I was wondering . . . You could always pop a bag of laundry into my house once a week. My cleaning lady often irons for me, I’m sure she wouldn’t mind—’

‘It’s very kind of you, but we’ll do our own washing and ironing,’ said Dad.

‘Well, if you think you can cope!’ said Rhiannon’s mum, making it plain by her tone that she didn’t feel Dad could cope at all.

‘Bye, Dad,’ I said, waving, so he had an excuse to escape.

He waved back worriedly, obviously seeing now how scruffy I looked. I gave him a big beaming smile to show him I didn’t care, stretching my mouth unnaturally wide, as if I was at the dentist’s.

‘You look like you’re going to take a bite out of someone, Floss,’ said Rhiannon.

Margot and Judy were sitting on the wall. They

heard

what Rhiannon said and started snorting with laughter. Then they took in my appearance and laughed all over again.

‘Oh. My. God,’ said Margot. ‘What do you look like, Floss? Has there been some major disaster so you’ve been, like, buried alive? Even your hair’s exploded! Look at it, all fluffed out and standing on end.’

‘And what’s that funny smell?’ said Judy, wrinkling her nose. ‘It’s like . . . chip fat!’

‘Well, that figures,’ said Margot. ‘Her dad runs this greasy spoon caff.’

‘It’s

not

greasy,’ I said fiercely. ‘It’s very special. My dad’s chip butties are

famous

.’

Margot and Judy cackled so much they very nearly fell off the wall. Rhiannon got the giggles too. She put her hands over her mouth but I could still see she was sniggering.

‘Don’t laugh at me!’ I said.

‘Well, you do look funny. But I know it’s not your fault,’ said Rhiannon. ‘Mum said I’ve got to make special allowances for you.’

‘Why have you got to make special allowances for old Smelly Chip?’ asked Margot.

‘Because her mum’s walked out on her.’

‘No she hasn’t! Don’t say that!’ I protested.

‘OK, OK, don’t get all touchy. I’m trying to be extra

nice

to you.’

She might

say

she was being extra nice but she certainly wasn’t acting it. I was scared I was going to start crying in front of them so I ran into school.

I hoped Rhiannon would run after me. I wanted her to put her arms round me and tell me I didn’t really look funny and she didn’t care what I looked like anyway because she was my best friend.

She didn’t run after me. She stayed smirking in the playground with Margot and Judy.

I locked myself in a lavatory and had a little private cry. Then I heard someone else come in. I clamped my hand over my nose and mouth to stop all the little snorty-snuffly sounds leaking out. I sat very still. Someone seemed to be standing there, waiting. Waiting for me?

‘Rhiannon?’ I called hopefully.

‘It’s Susan.’

‘Oh!’ I blew my nose as best I could on school toilet paper, flushed the loo and emerged, feeling foolish.

Susan looked at me. I glanced at myself in the mirror above the wash-hand basins. I looked even worse than I imagined – and now I had red eyes and a runny nose too.

‘I’ve got a cold,’ I said, splashing water on my face.

‘Yes,’ said Susan solemnly, although we both knew I was fibbing.

I tried wetting my hair while I was at it, to smooth it down. It went obstinately fluffier, springing up all over the place.

I sighed.

‘What?’ said Susan.

‘I hate my hair,’ I mumbled.

‘I think you’ve got lovely hair. I’d give anything to have fair curls.’

‘It’s not pretty yellow fair. It’s practically snow-white and much too curly. I can’t grow it. It grows

up

instead of down.’

‘I’m trying to grow mine, but it’s taking for ever,’ said Susan, tugging at her soft brown hair. ‘I’d love it to grow down past my shoulders but I’m going to have to wait two whole years, because hair grows only a quarter of an inch each month. Vitamin E is meant to be good for healthy growth so I’m eating lots of eggs and wholemeal bread and apricots and spinach, but it doesn’t seem to be having any noticeable effect so far.’

‘You know such a lot of stuff, Susan.’

‘No I don’t.’

‘You do – you know about the rate hair grows and vitamin E and all that.’

‘I don’t know how to make friends,’ said Susan.

We looked at each other.

‘I want to be your friend, Susan,’ I said. ‘It’s just . . .’

‘I know,’ said Susan. ‘Rhiannon.’

‘I’m sorry she’s so mean to you. Susan, your ballad – I thought it was so good.’

‘Oh no. Rhiannon was right about that. It was rubbish.’

‘Maybe . . . maybe you could come round and play some time, over at my dad’s?’ I said. ‘It’s not posh or anything. It’s just a funny café and we live over the top. I haven’t got a very nice bedroom but—’

‘I’d

love

to come,’ said Susan.

She smiled at me. I smiled back. I thought hard. Rhiannon would see if Susan came home with me after school.

‘What about Saturday?’ I said, glancing over my shoulder, scared that Rhiannon had crept up somehow and was standing right behind me, listening.

‘Saturday would be wonderful,’ said Susan.

‘Great!’ I swallowed. ‘The only thing is . . .’

‘Don’t worry, I won’t tell Rhiannon,’ said Susan.

I blushed. ‘

This

Saturday?’ I said.

‘Yep, this Saturday.’

‘You could come for tea. Only it might not be very . . . Do you like chip butties?’

Susan considered. ‘What are they?’ she said.

I stared at her in surprise. How could she know a million and one facts and figures and yet be so clueless about chip butties?

‘I know what a chip is,’ said Susan. ‘Fried potato.’

‘Well, you put a whole wodge of chips in a big soft white buttered roll – that’s a chip butty.’

‘Chips in a roll?’ said Susan.

‘It’s not exactly healthy eating,’ I said humbly. ‘But my dad specializes in

un

healthy eating, I’m afraid.’

‘It sounds a delicious idea,’ said Susan.

Then Margot and Judy came barging into the toilets. My heart started thudding. But it was all right: Rhiannon wasn’t with them.

Margot narrowed her eyes at me. ‘Were you, like, talking to Swotty Potty?’ she asked.

‘What are you, the Rhiannon private police force?’ said Susan. ‘No, she wasn’t talking to me. No one talks to me, you know that.’

She marched out of the toilets, with Margot and Judy making silly whistling noises after her. Then they turned to me. Margot still looked suspicious.

‘So what are you, like, doing here? Rhiannon’s looking for you.’

‘Is she?’

I ran past them. Susan was halfway down the corridor. I ran past her too. I ran all the way to our classroom and there was Rhiannon, sitting on her desk, swinging her legs impatiently. She had such lovely slender lightly tanned legs. Mine were like spindly white matchsticks.

‘There you are! What did you run off for? You are so

moody

now, Floss.’ Rhiannon sighed. ‘And if you don’t mind my saying so, you really do look awful. I bet Mrs Horsefield tells you off. You know how fussy she is, always going on about the boys not tucking their shirts in and telling all the girls off for rolling up their sleeves. You won’t be her special teacher’s pet today.’

‘Don’t be horrid!’

‘I’m not. I’m just pointing out the truth. You are, like,

so

paranoid.’

And you are, like, so stupid talking like Margot

, I thought inside my head, but I didn’t dare say it.

When Mrs Horsefield came into the classroom I hunched low at my desk, desperately smoothing my blouse and skirt, as if my hands were little irons. I was fine until halfway through maths, when Mrs Horsefield asked me to come up to the front of the class to do a sum on the board.

I stared at her, agonized, slumping so far down in my seat my chin was almost on the table.

‘Come on, Floss, don’t look so bashful,’ she said.

‘I – I can’t do the sum, Mrs Horsefield. Can’t you pick someone else?’ I suggested desperately.

‘I know maths isn’t your strong point but let’s see what you can do. It’s really quite simple if you work through it logically. Up you get!’

I had no option. I walked up to the board in my

crumpled

clothes and navy socks and muddy trainers. Mrs Horsefield looked startled. Margot and Judy giggled. I felt my cheeks flaming. I waited for Mrs Horsefield to start shouting at me. Astonishingly, she simply handed me the chalk and said quietly, ‘OK?’

I was anything but OK. I tried to do the stupid sum, my hand shaking so that the chalk stuttered on the board. I kept getting stuck. Mrs Horsefield gently prompted me, but I was in such a state I couldn’t think of the simplest answer.

I looked round helplessly – and there was Susan, mouthing the numbers at me. I wrote them quickly and then rushed back to my seat. Mrs Horsefield let me go, but when the bell went for break she beckoned me.

‘Can we have a word, Floss?’

‘Uh-oh,’ said Rhiannon.

‘Wait for me?’ I said.

‘Yeah, yeah,’ said Rhiannon, but she was drifting off as she spoke.

I stood at Mrs Horsefield’s desk. She waited until the last child had left the classroom. Then she put her head on one side, looking at me.

‘So why are you in such a sorry state? Dear oh dear! Did your mum sleep in this morning?’

‘Mum’s not here any more,’ I said, and I burst into tears.

‘Oh Floss!’ said Mrs Horsefield. She put her arm round me. ‘Come on, sweetheart, tell me all about it.’

‘Mum’s gone to Australia for six months. She

hasn’t

walked out on me, she’s coming back, she badly wanted me to go with her but I said I wanted to stay with my dad and I

do

, but I want Mum too!’ I sobbed like a silly baby.

Mrs Horsefield didn’t seem to mind. She reached into her handbag and found me a couple of tissues, one to wipe my eyes and one to blow my nose.

‘We could do with a whole handful of tissues for your shoes too,’ said Mrs Horsefield. ‘So you and Dad are finding it a bit difficult just now?’

‘Dad’s going to get an iron. We didn’t have time to clean my shoes. And I’ve lost all my white school socks,’ I wailed.

‘I’m sure you’ll get into a routine soon enough. Try to get your school things ready and waiting the night before. Don’t just rely on Dad. You’re a sensible girl, you can sort yourself out. It’s really quite simple – like the maths sum! You worked it out eventually, didn’t you? Well, with a little help from Susan.’

I blinked.

‘Susan’s such a nice girl,’ said Mrs Horsefield. ‘She could do with a friend right now.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘I want to be her friend.’ I lowered my voice in case anyone was hanging round

the

classroom door. ‘We

are

friends in secret. She’s coming round to my place this weekend. It’s just we can’t be friends at school because . . .’

Mrs Horsefield raised her eyebrows, but didn’t comment. ‘Oh well, I’m sure you girls will sort yourselves out, given time. Do come and have a little chat with me whenever you’re feeling upset or there’s some little problem at home. I’m not just here to teach you lessons, you know. I’m here to help you in any way I can.’

She paused, and then opened her desk drawer. There was a big paper bag inside. She opened it up and offered it to me. I saw one of her special pink iced buns with a big cherry on the top.

‘Go on, take it,’ she said.

‘But it’s not my birthday.’

‘It’s an

un

birthday bun for a little mid-morning snack.’

‘Isn’t it

your

mid-morning snack, Mrs Horsefield?’

‘I think I’ve been having far too many snacks, mid-morning or otherwise,’ said Mrs Horsefield, patting her tummy. ‘Go on, off you go.’

I took the bun and went out into the corridor. Rhiannon had said she’d wait but there was no sign of her. So I took my pink bun out of the paper bag and ate it all up myself. I especially savoured the cherry.