Capitol Men (28 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

To keep ourselves warm, we were obliged to walk to and fro in front of the depot in the sleet and while my dear children were suffering and crying from the severity of the cold. In faltering accents one of them inquired of me, "Why is this, ma? What have we done? Why can't we go in there and warm just like others?" Oh, sir, words are inadequate to express my feelings at that time. How my very soul burned with indignation. We had committed no offense. Our only crime was that of being American negroes.

Charlotte Forten, the black Philadelphia missionary teacher to the Sea Islands, assured Sumner, "I think only those who have suffered deeply from the cruel, cruel prejudice in this country can know how it embitters as well as depresses, how it gradually weakens and undermines one's faith in human natureâand, oh, how that loss of faith darkens the world, as nothing else can."

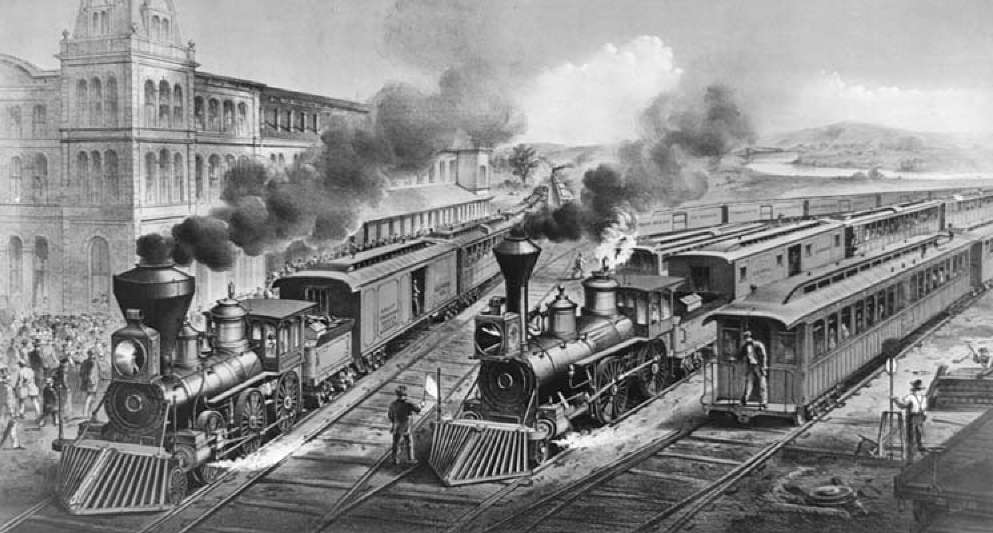

Even many Southern whites saw the inherent injustice. "For God's sake urge your Civil Rights Bill with all the vehemence of your soul," a man from Tennessee implored Sumner. "Yesterday I bought a R.R. ticket in company with four colored men. They paid the same price for theirs ... but I ... because my skin is white, was furnished a nice, soft, quishened [sic] seat in an elegant car; they were forced to occupy 'plank seats' in a filthy box ... In no sense of the word can this be right." The peripatetic Gilbert Haven was aghast at the conditions the railroads created. "The cars into which [blacks] are thrust are hideous pens," he wrote of a journey by rail in the South, where a fellow clergyman "of the offensive hue" was forced to ride "in a dirty, ill-ventilated, close-packed, unswept car, as mean as mean could be. Yet he was paying first-class fare and two score of seats in my clean car were vacant. But for him to have

asked to occupy one would have brought a revolver against his head."

One of the most disturbing testimonials came from Howard University, where it was reported that two black visitorsâWilliam White, a student from Fisk University in Nashville, and James Rapier (later a congressman from Alabama)âwere treated so poorly by the railroad that White was made seriously ill. Even though he and Rapier held first-class tickets, White reported, "from Nashville to Chattanooga I was compelled to ride in the car next to the baggage car, where smoking, drinking, and obscene conversation were carried on continually by low whites ... At stations for meals I could get nothing to eat ... At Chattanooga where I arrived at about 5 o'clock in the morning I was not permitted to enter the sitting room." White and Rapier were forced to stand on the dark station platform in the cold until their connecting train departed at 8

A.M.

On that train they were assigned to one half of the baggage car, where the door was left open to the elements because there was a corpse being shipped among the baggage. G. W. Mitchell of Howard remarked, as he passed along White's complaint to Sumner, "This is simply an illustration of what is occurring daily, and to which all are subjected in whose veins flows a perceptible amount of African blood."

In late 1872 the civil rights cause received a boost from an unusual source. John A. Coleman, a white businessman from Providence, Rhode Island, described in an article in the

Atlantic Monthly

how, after attempting to use a New Haven-New York City ticket for travel in the opposite direction, he had been arrested and bodily removed from a train. In "The Fight of a Man with a Railroad," Coleman accused the conductor of pettiness in refusing to honor his ticket, but the larger issue his story highlighted, and with which most readers could identify, was the routine insensitivity of railroad authorities and even the occasional bullying of passengers. This, Coleman wrote, was a particular failing of American railroads, and even an embarrassment, in light of the more civilized treatment accorded European rail travelers. The

New National Era

seized on Coleman's arrest and harsh treatment as valuable testimony; for once, a prominent white person had been victimized by the same "tyranny of railroad corporations" that affiicted black people every day. The

Era

pointed out that unlike Coleman, who had his case heard several times in court and had the satisfaction of venting his anger in the pages of a national magazine, blacks had no choice but to suffer in intimidated silence.

Black congressmen themselves were not immune to prejudice on the rails. "Here am I, a member of your honorable body, representing one

of the largest and wealthiest districts in the state of Mississippi," John Roy Lynch of Natchez told the House,

and yet when I leave my home to come to the capital of the nation ... to participate with you in making laws for the government of this great republic ... if I come by way of Louisville or Chattanooga, I am treated not as an American citizen, but as a brute. Forced to occupy a filthy smoking-car both night and day, with drunkards, gamblers, and criminals; and for what? Not that I am unable or unwilling to pay my way; not that I am obnoxious in my personal appearance or disrespectful in my conduct; but simply because I happen to be of a darker complexion. If this treatment was confined to persons of our own sex, we could possibly afford to endure it. But such is not the case. Our wives and our daughters, our sisters and our mothers, are subjected to the same insults and to the same uncivilized treatment.

"

IF I COME BY WAY OF LOUISVILLE OR CHATTANOOGA, I AM TREATED NOT AS AN AMERICAN CITIZEN, BUT AS A BRUTE

."

Joseph Rainey told a story of being physically removed from a hotel dining room in Suffolk, Virginia; another black representative asserted that while traveling from Boston to Washington he would need to "carry a basket of bread and wine with him" or go hungry. Robert Brown Elliott, never one to endure a slight, remonstrated with the proprietor when refused a meal at the café in the train station at Wilmington, North Carolina. "[Elliott] was compelled to leave the restaurant or have

a fight for it," lawmaker Richard "Daddy" Cain told Congress. "He showed fight ... and got his dinner." The next time Elliott and Cain passed through Wilmington, they tried to avoid another scene by having food and coffee brought to them on the train, but the train master refused, accusing the congressmen of "putting on airs." Elliott later won some measure of revenge at a restaurant in Washington, where a young white man complained to the management about his presence at a nearby table. Elliott made inquiries, learned the fellow clerked in the Treasury Department, and arranged to have him fired.

Along with railroads, hotels were also an embattled civil rights terrain. Would whites consent to sit in lobbies alongside blacks and take meals with them, or stay in hotel rooms, use bathrooms, and sleep in beds that blacks had occupied? The answer, generally, was a resounding "No!" Hotel managers warned that they would shut down their businesses completely if legislators continued to "push on the dusky column." Even the great Frederick Douglass had been refused dinner at the Planter's House in St. Louis. Staying at the hotel in 1871 while on a lecture tour, he had gone out one afternoon to do some visiting. When he returned for dinner, he was challenged at the door to the dining room and asked if he was a registered guest; he replied that he was, but when the registration book was consulted, it was found that his name had been scratched out. Douglass demanded an explanation, but the hotel offered none. The

New National Era

indignantly cited Douglass's reputation and the fact that he was welcome in some of the world's most dignified salons and lecture halls, and lamented the fact that "Mr. Douglass's experience ... is the experience of thousands of his race all over the country." To stamp out "the accursed prejudice which deprives colored men of the common courtesies of civilized intercourse," the paper called for "legislation as will teach snobbery everywhere that men who were good enough to fight to save the life of the Republic are also good enough to enjoy the common rights belonging to citizens."

The reports of Douglass's mistreatment prompted P.B.S. Pinchback's

Louisianian

to make a disheartening association, observing that "the roasting of a poor negro lad with kerosene at Port Jervis a few days ago by two or three white brutes, is but the crystallization of a sentiment which in less defined form shut Frederick Douglass from a hotel in St. Louis ... and turns up its fastidious nose at the negro in street car, the church, or the theatre."

St. Louis also offered harsh treatment to Congressman Lynch, in what would prove an embarrassing gaffe. Beginning in 1869, town fathers

there had held occasional "capital removal conventions" as part of a public relations effort to lobby the rest of the country on the idea of relocating the nation's capital from Washington to St. Louis. Lynch, as a member of Congress, was invited to town to be wined and dined and persuaded on the matter by local boosters. But, arriving late at night, he was turned away from the Planter's House, where Mississippi's other congressmen were staying, and he wound up wandering the streets in the middle of the night with his luggage, unable to find a hotel. The incident made the newspapers the next day, much to the chagrin of the host committee. The nation's capital, of course, remained in Washington.

More than that of other public accommodations, the potential integration of hotels and restaurants produced the greatest alarm over "social equality," which whites feared would lead to the eventual amalgamation of America's distinctive racial groups. "Social equality" was one of the most highly charged terms in late-nineteenth-century America, but a misleading "bugbear," as Alonzo Ransier remarked. Attaining equal rights in the public sphere did not imply that blacks and whites would be forced into social intimacy; only whites opposed to civil rights laws insisted on that interpretation. Sumner himself stressed that his proposed law would not regulate social interactions. Any person could freely choose his friends and associates and do so within the walls of his private dwelling, but "he cannot appropriate the sidewalk to his own exclusive use, driving into the gutter all whose skin is less white than his own."

There was of course great hypocrisy to the charge that "social equality" was being forced on the South. As civil rights advocates never failed to point out, whites had for decades permitted close relations with blacks as servants and had indulged them as sexual partners and blood kin. "Why this fear of the negro since he has been a freedman," asked Rainey, "when in the past he was almost a household god, gamboling and playing with the children of his old master? And occasionally it was plain to be seen that there was a strong family resemblance between them." Thomas Cardozo, Mississippi's light-skinned superintendent of education, liked to say he had no trouble understanding what social equality wasâhe saw "a practical demonstration" of it "whenever I look in the glass."

Charles Sumner envisioned his civil rights act as a final phase in the evolution of national authority that had begun with the Civil War itself, in

which the North denied the Confederate states their right to secede. The advance had continued with the Emancipation Proclamation, the Thirteenth Amendment, the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, the Reconstruction Acts, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and the Enforcement Actsâdocuments that presumed the constitutional duty of the federal government to establish and defend the status of residents of the United States. Sumner's legislation also relied, ironically, on a widely disgraced antebellum lawâthe Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which had criminalized the abetting of slave runaways or the failure to return them to their owners. In practice, the Fugitive Slave Act caused few runaway slaves to be returned to their Southern owners, and its implication that all Americans, including Northerners, were now to act as "slave catchers" only served to agitate public opinion in the run-up to civil war. But postwar civil rights advocates like Sumner found a technical advantage to be made of this heinous law, for it had required the involvement of federal officers and judges. By making it incumbent upon the national government to use its branches and agencies to defend a slaveholder's right to his property, the law created a precedent for the idea that an individual's constitutional rights could be not only recognized but actively enforced by Congress.

Sumner was often criticized for bringing too much emotion to the law and ignoring its intricacies, although what really separated him from his congressional brethren was his greater willingness to shape existing laws to meet present social needs, an idea that would not fully engage the American legal establishment for another half-century. One of Sumner's heroes was the eminent New England jurist Joseph Story, who taught that although common law deserved respect for being based on precedent, it was not to be regarded as infallible; wise lawmakers looked not solely backward for guidance, but around them as well. When a fellow senator protested to Sumner, "I have sworn to support the Constitution, which, as I understand, binds me

not

to vote for anything that I believe to be unconstitutional," Sumner replied, "I have

also

sworn to support the Constitution, and it binds me to vote for anything for human rights."