Carlito's Way: Rise to Power

C

ARLITO’S

W

AY

Rise to Power

Edwin Torres

Copyright © 1975 by Edwin Torres

Introduction copyright © 2005 by Mario Van Peebles

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Originally published in 1975 by Saturday Review Press/

E. P. Dutton, New York

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Torres, Edwin.

Carlito’s way: rise to power / Edwin Torres.

p. cm.

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4750-0

1. Hispanic American criminals—Fiction. 2. Organized crime—Fiction. 3. New York (N.Y.)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3570.O697C37 2005

813’.54—dc22 2005045984

Black Cat

a paperback original imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

To the memory of Orlando Cardona,

the best of the 107th Street bunch, killed in action,

February 4, 1951, Wonju, Korea

Introduction

Americans made more Western and gangster flicks than any other genre. And in a way the gangster flick is the urban Western. The city replaces the wild, wild West, where anything is possible—the American dream, for any bad motherfucker tough enough to grab it; the immigrant fantasy of infinite possibility, but not without a price; complete with gamblers, con men, fast women, and of course, the outlaw or the gangster.

Carlito’s Way

has all that. As a filmmaker I’ve done both Westerns and gangster flicks, but what hit me when I first read Eddie Torres’s book was the voice: rich, authentic, and lyrical like the sway of a Latina’s hips, with the mystery and undeniable rhythm of the street, like congas pounding beneath her strut. From page 1 you smell the fried onions, the bodegas, the cheap perfume of young whores, and the stench of back-alley wino piss.

This is not a lofty prince’s tale of heroic deeds. This is the gritty story of an urban cowboy’s rise to power. A member of the

lumpenproletariat

, someone uncomfortably

close to us, or rather the us we fear we could be if dealt similar circumstances. There but for the grace of God go we? This is the tale of a flawed Everyman, trying to get loot, get laid, and survive with a modicum of dignity in a world bent on kicking his New-Yorican ass.

In an age where some heads of state view the world in terms of an axis of evil and “evildoers,” then by logical extension there must be “good doers.” This reductive perspective leads to a polarized good guy vs. bad guy look at humanity. The reality, of course, is that we all have the capacity for good and evil, and that complex grey area in between is the stage where writer Eddie Torres dances.

His Honor Torres, a practicing New York City judge, writes of outlaws without ever casting the stone of judgment at his subjects. As Bob Dylan sang, he “knows too much to argue or to judge.” Torres takes us on a tour through the fertile underworld of the fifties and sixties where good guys and bad guys were often one and the same. Using rich Latino ghetto prose we follow our lead character, Carlito Brigante, on an odyssey through post–World War II New York City during a time when American apartheid was alive and well.

Carlito, a product of Spanish Harlem, seems wonderfully ignorant of the turbulent political times surrounding him. A survivor, a Po-rican caught between the Italians on one side and the blacks on the other. He is a minority of minorities, unwilling to bow or to bend in a world where the rules are laid down by the “haves” to keep the “have nots” from ever having. Overtly apolitical, Carlito seems instinctually aware of the injustice inherent in the system, and the “isms” that inevitably go with it: lookism,

sexism, racism, classism. He is a man conscious of his own mortality and limitations and the cost of standing up in a world designed to keep the underclass down. The nail that sticks out is the one that gets hammered upon.

Frantz Fanon points out that the most successful colonizers always left behind the church and the schools, to socialize the oppressed to the oppressor’s point of view. (If Brother Frantz was alive today, he’d probably add films to that list.)

Interesting that Carlito seems suspicious of both; like a con man sensing some greater systemic con, he avoids any doctrine, academic or religious, that would have him kneel and pray for pie in the sky.

He lives by his own moral code, the code of the street, the “hodedors,” at a time when there was still honor among thieves. Carlito is a gentleman rogue, a product of the juvenile detention centers, raised without a father, and having lost his mother at an early age. Carlito learns to hustle, having decided early on that he’d rather be a hammer than a nail, a fucker than a fuckee.

While doing a stretch in the joint he is adopted by his only true family, his big brothers and future partners in crime—Rocco Fabrizi and, the character I play, Earl Bassey.

Meanwhile on the outside, the civil rights movement was starting to gain momentum. During the sixties Dr. King was calling for freedom by “peaceful means” from the pulpit of the black Baptist church. Uptown in Harlem Minister Malcolm X was in the Muslim temple calling for freedom “by any means necessary.” When King reaches across the cultural and racial divide,

marching on Washington with people of all colors, taking a stance on American poverty and the Vietnam War, he became a perceived threat to J. Edgar Hoover and the COINTEL-PRO gang and was soon taken out. At the end of his arc, Malcolm returns from his pilgrimage to Mecca and talks of having prayed next to Muslims of all colors. He also goes international, reframing the issue of civil rights as one of human rights. Malcolm moves to bring these issues into the World Court of the UN and broaden his constituency. He too becomes a perceived threat to the status quo and is taken out.

Staying in one’s own racial or cultural box makes one vulnerable to the old divide and conquer, us vs. them, “evil doers” vs. “good doers” routine, but crossing the racial divide, connecting the dots, has always been risky business; doing so in the underworld of the sixties was no exception. These three brothers of other colors from other mothers—black, white, and Puerto Rican—get out of the joint and come together in spite of the odds. It is interesting that the racial combination of young Carlito’s two surrogate parents or big brothers, Italian and black, would yield something close to Puerto Rican.

These three men form an alliance, a brotherhood, exploiting the racially divided underworld in pursuit of yet another color—green, the color of money—and in that sense their union is revolutionary. Carlito, Rocco, and Earl make their future in the illegal heroin trade, in the tradition of prominent Americans like Joe Kennedy, who profited from illegal alcohol during Prohibition. With an “if I don’t deal it somebody else will” mentality, they are businessmen meeting the demands for their escapist

product with supply. They are what the Black Panthers referred to as social parasites.

As Earl’s pseudo-revolutionary younger brother, Reggie, says, “If you [hustlers] don’t join the ranks of the oppressed then you’ll be put up against the wall with the rest of them.” Ultimately the revolution never came—the FBI’s COINTELPRO was a success neutralizing black leadership.

With the death of both Malcolm and Martin, the colored community that once sang “We Shall Overcome” was righteously pissed off and started singing “Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud.” Across America there were riots. Voter registration by blacks shot up. Militancy was on the rise, young folks both black and white where organizing and protesting the war in Vietnam.

Some would argue that this rise in militancy was deliberately medicated with the influx of drugs into the inner cities. Junkies don’t vote, organize, or question authority. Today’s gangs inherited the bravado of the Black Power movement without the political ideology to support it. Any last songs of political protest or black pride were drowned out by the booming bass of so-called gangsta rap, extolling the virtues of mindless capitalism and taking it to new levels. Why just put the gold around your wrist or your neck like the old-school gangasters when you can put the shit in your teeth too? Ghettos became “self-cleaning ovens” with gangsters preying upon each other, adopting a genocidal, black-on-black, bling-bling, “I gotta get mine and kill my brother” mentality. The revolution would not be televised, it would implode.

In Elaine Brown’s

Taste of Power

, she writes that in the

early seventies coke was starting to flood the ghetto and some cops were looking the other way. “Cocaine in Oakland is cheap now, no longer the drug of choice for the rich and famous, it’s coming into Oakland at low prices from I don’t know where…. Big-time dealers are establishing turf.” Whether this was deliberate or not, no one could argue that although there were no poppy fields in the ghetto, and no gun-manufacturing plants, there was now an abundance of both drugs and guns in the hood.

The logistics required in importing this contraband across America’s inner cities requires the cooperation of those significantly up the food chain from the Carlitos of the world. Torres’s book ends before the superstar gangsters of the late seventies and eighties inherited the mantle.

Gangsters like Nicky Barnes, who was one of the models for Neno Brown in my film

New Jack City

, would grace the cover of

The New York Times Magazine

as Mr. Untouchable. Barnes did for narcotics what Ford did for the automotive industry. The new upstart dealers would not inherit Carlito’s code of ethics. Mobsters would start to turn states’ evidence, ratting each other out. The Carlitos, Roccos, and Earls of the world would be a dying breed.

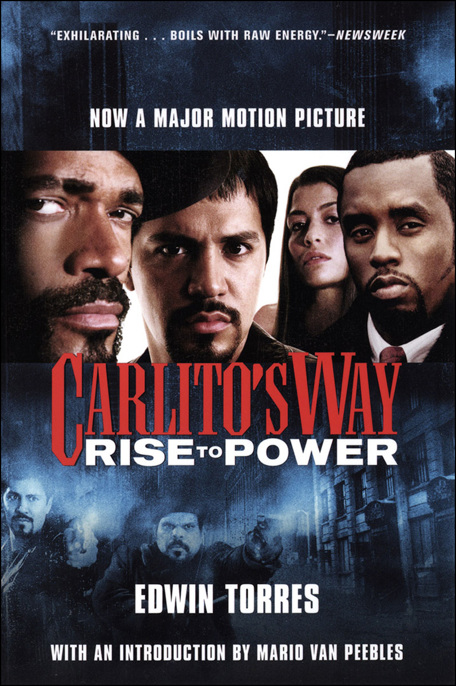

Torres’s book, an edgy social commentary on America’s underworld, captures an era with an authenticity that makes one wonder if the good judge led a double life. Multiracial, visual, and brutally honest, it’s no surprise that this book, like his others, has inspired a film:

Carlito’s Way: The Rise to Power

.

—Mario Van Peebles

June 21, 2005

C

ARLITO’S

W

AY

S

OONER OR LATER, A THUG WILL TELL HIS TALE. WE ALL WANT

to go on record. So let’s hear it for all the hoods. The Jews out of Brownsville. The Blacks on Lenox Avenue. The Italians from Mulberry Street. Like that. Meanwhile, the Puerto Ricans been gettin’ jammed since the forties and ain’t nobody said nothin’. We been laid, relayed, and waylaid and nobody wants to hear about it. Well, I’m gonna lay it on you one time, for the record

.

Who these people? Puerto Ricans. They come from an island a hundred long by thirty-five miles wide. They come in all sizes, colors, and shapes. They got a little of everybody. Heart like the Jews, soul like the Blacks, balls like the Italians. They hit New York in the 1940s, the wrong time. But like when is it right, when your face don’t help, your accent ain’t French, and your clothes don’t fit? They hung in anyway—most of the tickets were one way. So they filed into the roach stables in Harlem and the South Bronx. They sat behind the sewing machines

and stood behind the steam tables. In other words, they busted their ass, they went for the Dream. Most of them

.

A handful couldn’t handle the weight at the bottom of the totem pole. They wouldn’t squat, couldn’t bend. Had to take their shot. Them was the

hodedores,

hoodlums. Hard nose. And like the thugs from any group they went for the coin of the realm, head on

.

I’m talking from the far shore looking back on thirty years. At least I made it to the other side. Most of my crew got washed on the way. And if survivors don’t talk about it, who’s gonna know we was here, right? So here’s how it went down for one P.R., me, Carlito Brigante

.

1

I

CAME ON THE SCENE IN THE 1930S

. M

E AND MY MOMS

. Brigante Sr. had long since split back to Puerto Rico. Seem like we was in every furnished room in Spanish Harlem. Kind of hazy some of it now, but I can remember her draggin’ me by the hand from place to place—the clinic on 106th Street, the home relief on 105th Street, the Pentecostal church on 107th Street. That was home base, the church. Kids used to call me a “hallelujah”—break my chops. My mom was in there every night bangin’ on a tambourine with the rest of them. Sometimes they’d get a special

reverendo

who’d really turn them on. That’s when the believers,

feligreses

, would start hoppin’ and jumpin’—then they’d be faintin’ on the floor and they’d wrap them in white sheets. I remember I didn’t go for this part. I was close to my mom, it was just me and her.