Cat O'Nine Tales: And Other Stories (30 page)

Read Cat O'Nine Tales: And Other Stories Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

Malik was a

white-collar criminal who was well capable of holding down a serious job.

However, as a young man he had quickly discovered that he possessed enough

charm and native cunning to con naive people, particularly old ladies, out of

large sums of money, without having to exert a great deal of effort.

His first scam

was not unique to Mumbai. All he required was a small printing press, some

headed notepaper and a list of widows. Once he’d obtained the latter–on a daily

basis from the obituary column of the

Mumbai

Times

–he was in business. He specialized in selling shares in overseas

companies that didn’t exist. This provided him with a regular income, until he

tried to sell some stock to the widow of another conman.

When Malik was

charged, he admitted to having made over a million rupees, but the Commissioner

suspected that it was a far larger sum; after all, how many widows were willing

to admit they had been taken in by Malik’s charms? Malik was sentenced to five

years in Pune jail and Kumar lost touch with him for nearly a decade.

Malik was back

inside again after he’d been arrested for selling flats in a high-rise

apartment block on land that turned out to be a swamp. This time the judge sent

him down for seven years.

Another decade

passed.

Malik’s third

offense was even more ingenious, and resulted in an even longer sentence. He

appointed himself a life-assurance broker. Unfortunately the annuities never

matured–except for Malik.

His barrister

suggested to the presiding judge that his client had cleared around twelve

million rupees, but as little of the money was available to be given back to

those who were still living, the judge felt that twelve years would be a fair

return on this particular policy.

By the time the

Commissioner had turned the last page, he was still puzzled as to why Malik

could possibly want to see him. He pressed a button under the desk to alert his

secretary that he was ready for his next appointment.

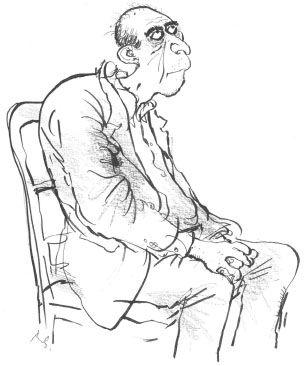

Commissioner

Kumar glanced up as the door opened. He stared at a man he barely recognized.

Malik must have been ten years younger than he was, but they would have passed

for contemporaries.

Although

Malik’s file stated that he was five foot nine and weighed a hundred and

seventy pounds, the man who walked into his office did not fit that

description.

The old con’s

skin was lined and parched, and his back was hunched, making him appear small

and shrunken.

Half a life

spent in jail had taken its toll.

He wore a white

shirt that was frayed at the collar and cuffs, and a baggy suit that might at

some time in the past have been tailored for him. This was not the

selfconfident

man the Commissioner had first arrested over

thirty years ago, a man who always had an answer for everything.

Malik gave the

Commissioner a weak smile as he came to a halt in front of him.

“Thank you for

agreeing to see me, sir,” he said quietly. Even his voice had shrunk.

The

Commissioner nodded, waved him to the chair on the other side of his desk and

said, “I have a busy morning ahead of me, Malik, so perhaps you could get

straight to the point.”

“Of course,

sir,” Malik replied, even before he’d sat down. “It’s simply that I am looking

for a job.”

The

Commissioner had considered many reasons why Malik might want to see him, but

seeking employment had not been among them.

“Before you

laugh,” continued Malik, “please allow me to put my case.”

The

Commissioner leaned back in his chair and placed the tips of his fingers

together, as if in silent prayer.

“I have spent

too much of my life in jail,” said Malik. He paused. “I’ve recently reached the

age of fifty, and can assure you that I have no desire to go back inside

again.”

The

Commissioner nodded, but didn’t express an opinion.

“Last week,

Commissioner,” continued Malik, “you addressed the annual general meeting of

the Mumbai Chamber of Commerce. I read your speech in the

Times

with great interest. You expressed the view to the leading

businessmen of this city that they should consider employing people who had

served a prison sentence–give them a second chance, you said, or they will

simply take the easy option and return to a life of crime. A sentiment I was

able to agree with.”

“But I also

pointed out,” interrupted the Commissioner, “that I was only referring to first

offenders.”

“Exactly my

point,” countered Malik.

“If you

consider there is a problem for first offenders, just imagine what I come up

against, when I apply for a job.” Malik paused and straightened his tie before

he continued. “If your speech was sincere and not just delivered for public

consumption, then perhaps you should heed your own advice, and lead by

example.”

“And what did

you have in mind?” asked the Commissioner.

“Because you

certainly do not possess the ideal qualifications for police work.”

Malik ignored

the Commissioners sarcasm and plowed boldly on. “In the same paper in which

your speech was reported, there was an advertisement for a filing clerk in your

records department. I began life as a clerk for the P & O Shipping Company,

right here in this city. I think that you will find, were you to check the

records, that

I carried out that job with enthusiasm and

efficiency, and on that occasion left with an unblemished record.”

“But that was

over thirty years ago,” said the Commissioner, not needing to refer to the file

in front of him.

“Then I will

have to end my career as I began it,” replied Malik, “as a filing clerk.”

The

Commissioner didn’t speak for some time while he considered Malik’s

proposition. He finally leaned forward, placed his hands on the desk, and said,

“I will give some thought to your request, Malik. Does my secretary know how to

get in touch with you?”

“Yes, she does,

sir,” Malik replied as he rose from his place. “Every night I can be found at

the YMCA hostel on Victoria Street.” He paused. “I have no plans to move in the

near future.”

Over lunch in

the officers’ dining room, Commissioner Kumar briefed his deputy on the meeting

with Malik.

Anil Khan burst

out laughing. “Hoist with your own petard, Chief,” he said with considerable

feeling.

“True enough,”

replied the Commissioner as he helped himself to another spoonful of rice, “and

when you take over from me next year, this little episode will serve to remind

you of the consequences of your words, especially when they are delivered in

public.”

“Does that mean

that you are seriously considering employing the man?” asked Khan, as he stared

across the table at his boss.

“Possibly,”

replied Kumar. “Why, are you against the idea?”

“You are in

your last year as Commissioner,” Khan reminded him, “with an enviable

reputation for probity and competence. Why take a risk that might jeopardize

such a fine record?”

“I feel that’s

a little over-dramatic,” said the Commissioner. “Malik’s a broken man, which

you would have seen for yourself had you been present at the meeting.”

“Once a conman,

always a conman,” replied Khan. “So I repeat, why take the risk?”

“Perhaps

because it’s the correct course of action, given the circumstances,” replied

the Commissioner. “If I turn Malik down, why should anyone bother to listen to

my opinion ever again?”

“But a filing

clerk’s job is particularly sensitive,” remonstrated Khan. “Malik would have

access to information that should only be seen by those whose discretion is not

in question.”

“I’ve already

considered that,” said the Commissioner. “We have two filing departments: one

in this building, which is, as you rightly point out, highly sensitive, and

another based on the outskirts of the city that deals only with dead cases,

which have either been solved or are no longer being followed up.”

“I still

wouldn’t risk it,” said Khan as he placed his knife and fork back on the plate.

“I’ve cut down

the risk even more,” responded the Commissioner. “I’m going to place Malik on a

month’s trial. A supervisor will keep a close eye on him, and then report

directly back to me. Should Malik put so much as a toe over the line, he’ll be

back on the street the same day.”

“I still

wouldn’t risk it,” repeated Khan.

On the first of

the month, Raj Malik reported for work at the police records department on 47

Mahatma Drive, on the outskirts of the city. His hours were eight a.m. to six

p.m. six days a week, with a salary of nine hundred rupees a month.

Malik’s daily

responsibility was to visit every police station in the outer district, on his

bicycle, and collect any dead files.

He would then

pass them over to his supervisor, who would file them away in the basement,

rarely to be referred to again.

At the end of

his first month, Malik’s supervisor reported back to the Commissioner as

instructed. “I wish I had a dozen

Maliks

,” he told

the chief. “Unlike today’s young, he’s always on time, doesn’t take extended

breaks, and never complains when you ask him to do something not covered by his

job description. With your permission,” the supervisor added, “I would like to

put his pay up to one thousand rupees a month.”

The

supervisor’s second report was even more glowing. “1 lost a member of staff

through illness last week, and Malik took over several of his responsibilities

and somehow still managed to cover both jobs.”

The

supervisor’s report at the end of Malik’s third month was so flattering that

when the Commissioner addressed the annual dinner of the Mumbai Rotary Club,

not only did he appeal to its members to reach out their hands to ex-offenders,

but he went on to assure his audience that he had heeded his own advice and

been able to prove one of his long-held theories. If you give former prisoners

a real chance, they won’t reoffend.

The following

day, the

Mumbai Times

ran the

headline:

COMMISSIONER LEADS BY EXAMPLE

Kumar’s

sentiments were reported in great detail, alongside a photo of Raj Malik, with

the byline,

a reformed character.

The

Commissioner placed the article on his deputy’s desk.

Malik waited

until his supervisor had left for his lunch break. He always drove home just

after twelve and spent an hour with his wife. Malik watched as his boss’s car

disappeared out of sight before he slipped back down to the basement. He placed

a stack of papers that needed to be filed on the corner of the counter, just in

case someone came in unannounced and asked what he was up to.

He then walked

across to the old wooden cabinets that were stacked one on top of the other. He

bent down and pulled open one of the files. After nine months he had reached

the letter P and still hadn’t come across the ideal candidate. He had already

thumbed through dozens of

Patels

during the previous

week, dismissing most of them as either irrelevant or inconsequential for what

he had in mind. That was until he reached one with the first initials H.H.

Malik removed

the thick file from the cabinet, placed it on the counter top and slowly began

to turn the pages. He didn’t need to read the details a second time to know

that he’d hit the jackpot.

He scribbled

down the name, address and telephone numbers neatly on a slip of paper, and

then returned the file to its place in the cabinet. He smiled. During his tea

break, Malik would call and make an appointment to see Mr. H.H. Patel.

With only a few

weeks to go before his retirement, Commissioner Kumar had quite forgotten about

his prodigy. That was until he received a call from Mr. H.H. Patel, one of the

city’s leading bankers. Mr. Patel was requesting an urgent meeting with the

Commissioner–to discuss a personal matter.

Commissioner

Kumar looked upon H.H. not only as a friend, but as a man of integrity, and

certainly not someone who would use the word urgent without good reason.

Kumar rose from

behind his desk as Mr. Patel entered the room. He ushered his old friend to a

comfortable chair in the corner of the room and pressed a button under his

desk. Moments later his secretary appeared with a pot of tea and a plate of

Bath Oliver biscuits. The Deputy Commissioner followed in her wake.

“I thought it

might be wise to have Anil Khan present for this meeting, H.H., as he will be

taking over from me in a few weeks’ time.”

“I know of your

reputation, of course,” said Mr. Patel, shaking Khan warmly by the hand, “and I

am delighted that you are able to join us.”

Once the

secretary had served the three men with tea, she left the room.

The moment the

door was closed, Commissioner Kumar dispensed with any more small talk. “You

asked to see me urgently, H.H., concerning a personal matter.’