Cat O'Nine Tales: And Other Stories (29 page)

Read Cat O'Nine Tales: And Other Stories Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

With the

exception of the immediate family and those guests selected to sit on the long

top table by the side of the dance floor, there were, in fact, very few people

George had ever set eyes on before.

George took his

place at the center of the top table, with Isabella on his right and Alexis on

his left. Once they were all seated, course after course of overladen dishes

was set before his guests, and the wine flowed as if it were a Bacchanalian

orgy rather than a small island wedding.

But then

Bacchus–the god of wine–was a Greek.

When, in the

distance, the cathedral clock chimed eleven times, George hinted to the best

man that perhaps the time had come for him to make his speech.

Unlike George,

he

was

drunk, and certainly wouldn’t

be able to recall his words the following morning. The groom followed, and when

he tried to express how fortunate he was to have married such a wonderful girl,

once again his young friends leaped onto the dance floor and fired their

pistols in the air.

George was the

final speaker. Aware of the late hour, the pleading look in his guests’ eyes,

and the half-empty bottles littering the tables around him, he satisfied

himself with wishing the bride and groom a blessed life, a euphemism for lots

of children. He then invited those who still could to rise and toast the health

of the bride and groom. Isabella and Alexis, they all cried, if not in unison.

Once the

applause had died down, the band struck up. The groom immediately rose from his

place, and, turning to his bride, asked her for the first dance.

The newly

married couple stepped onto the dance floor, accompanied by another volley of

gunfire. The groom’s parents followed next, and a few minutes later George and

Christina joined them.

Once George had

danced with his wife, the bride and the groom’s mother, he made his way back to

his place in the center seat of the top table, shaking hands along the way with

the many guests who wished to thank him.

George was

pouring himself a glass of red wine–after

all,

he had

performed all his official duties–when the old man appeared.

George leaped

to his feet the moment he saw him standing alone at the entrance to the garden.

He placed his glass back on the table and walked quickly across the lawn to

welcome the unexpected guest.

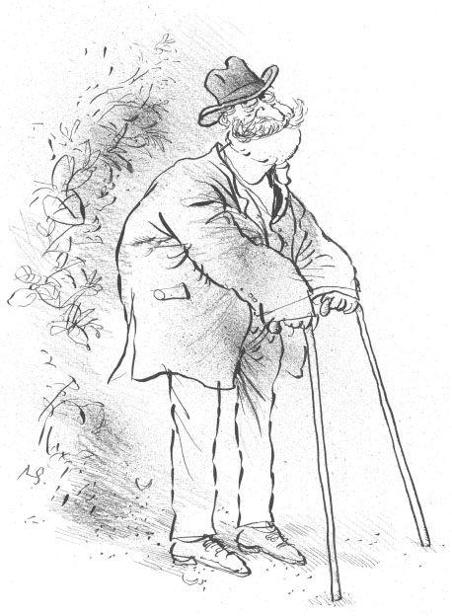

Andreas

Nikolaides

leaned heavily on his two walking sticks. George

didn’t like to think how long it must have taken the old man to climb up the

path from his little cottage, halfway down the mountain. George bowed low and

greeted a man who was a legend on the island of Cephalonia as well as in the

streets of Athens, despite the fact that he had never once left his native

soil. Whenever Andreas was asked why, he simply replied, “Why would anyone

leave Paradise?”

In 1942, when

the island of Cephalonia had been overrun by the Germans, Andreas

Nikolaides

escaped to the hills and, at the age of

twenty-three, became the leader of the resistance movement.

He never left

those hills during the long occupation of his homeland and, despite a handsome

bounty being placed on his head, did not return to his people until, like Alexander,

he had driven the intruders back into the sea.

Once peace was

declared in 1945,

Andreas

returned in triumph. He was elected mayor of Cephalonia, a position which he

held, unopposed, for the next thirty years. Now that he was well into his

eighties, there wasn’t a family on Cephalonia who did not feel in debt to him,

and few who didn’t claim to be a relative.

“Good evening,

sir,” said George stepping forward to greet the old man.

“We are honored

by your presence at my niece’s wedding.”

“It is I who should

be honored,” replied Andreas, returning the bow.

“Your niece’s

grandfather fought and died by my side. In any case,” he added with a wink,

“it’s an old man’s prerogative to kiss every new bride on the island.”

George guided

his distinguished guest slowly round the outside of the dance floor and on

toward the top table.

Guests stopped

dancing and applauded as the old man passed by. George insisted that Andreas

take his place in the center of the top table, so that he could be seated

between the bride and groom.

Andreas

reluctantly took his host’s place of honor. When Isabella turned to see who had

been placed next to her, she burst into tears and threw her arms around the old

man. “Your presence has made the wedding complete,” she said.

Andreas smiled and,

looking up at George, whispered, “I only wish I’d had that effect on women when

I was younger.”

George left

Andreas seated in his place at the center of the top table, chatting happily to

the bride and groom. He picked up a plate and walked slowly down a table laden

with food. George took his time selecting only the most delicate morsels that

he felt the old man would find easy to digest. Finally he chose a bottle of

vintage wine from a case that his own father had presented to him on the day of

his wedding. George turned back to take the offering to his honored guest just

as the chimes on the cathedral clock struck twelve, hailing the dawn of a new

day.

Once more, the

young men of the island charged onto the dance floor and fired their pistols

into the air, to the cheers of the assembled guests. George frowned, but then

for a moment recalled his own youth. Carrying the plate in one hand and a

bottle of wine in the other, he continued walking back toward his place in the

center of the table, now occupied by Andreas

Nikolaides

.

Suddenly,

without warning, one of the young bandoliers, who’d had a little too much to

drink, ran forward and tripped on the edge of the dance floor, just as he was

discharging his last shot.

George froze in

horror when he saw the old man slump forward in his chair, his head falling

onto the table. George dropped the bottle of wine and the plate of food onto

the grass as the bride screamed. He ran quickly to the center of the table, but

it was too late. Andreas

Nikolaides

was already dead.

The large,

exuberant gathering was suddenly in turmoil, some screaming, some weeping,

while others fell to their knees, but the

majority were

hushed into a shocked, somber silence, unable to grasp what had taken place.

George bent

down over the body and lifted the old man into his arms. He carried him slowly

across the lawn, the guests forming a corridor of bowed heads, as he walked

toward the house.

George had just

bid five thousand pounds for two seats at a West End musical that had already

closed when he told me the story of Andreas

Nikolaides

.

“They say of

Andreas that he saved the life of everyone on that island,” George remarked as

he raised his glass in memory of the old man. He paused before adding, “Mine

included.”

“

W

hy

does he want to see

me?”

asked

the Commissioner.

“He says it’s a

personal matter.”

“How long has

he been out of prison?”

The

Commissioner’s secretary glanced down at Raj Malik’s file. “He was released six

weeks ago.”

Naresh

Kumar stood up, pushed back his chair and began

pacing around the room; something he always did whenever he needed to think a

problem through.

He had

convinced himself–well, almost–that by regularly walking round the office he

was carrying out some form of exercise. Long gone were the days when he could

play a game of hockey in the afternoon, three games of squash the same evening

and then jog back to police headquarters. With each new promotion, more silver

braid had been sewn on his epaulet and more inches appeared around his waist.

“Once I’ve

retired and have more time, I’ll start training again,” he told his number two,

Anil Khan. Neither of them believed it.

The

Commissioner stopped to stare out of the window and look down on the teeming

streets of Mumbai some fourteen floors below him: ten million inhabitants who

ranged from some of the poorest to some of the wealthiest people on earth. From

beggars to billionaires, and it was his responsibility to police all of them.

His predecessor had left him with the words: “At best, you can hope to keep the

lid on the kettle.” In less than a year, when he passed on the responsibility

to his deputy, he would be proffering the same advice.

Naresh

Kumar had been a policeman all his life, like his

father before him, and what he most enjoyed about the job was its sheer

unpredictability. Today was no different, although a great deal had changed

since the time when you could clip a child across the ear if you caught him

stealing a mango. If you tried that today, the parents would sue you for

assault and the child would claim he needed counseling. But, fortunately, his

deputy Anil Khan had come to accept that guns on the street, drug dealers and

the war against terrorism were all part of a modern policeman’s lot.

The

Commissioner’s thoughts returned to Raj Malik, a man he’d been responsible for

sending to prison on three occasions in the past thirty years. Why did the old

con want to see him? There was only one way he was going to find out. He turned

to face his secretary.

“Make an

appointment for me to see Malik, but only allocate him fifteen minutes.”

The

Commissioner had forgotten that he’d agreed to see Malik until his secretary

placed the file on his desk a few minutes before he was due to arrive.

“If he’s one minute

late,” said the Commissioner, “

cancel

the

appointment.”

“He’s already

waiting in the lobby, sir,” she replied.

Kumar frowned,

and flicked open the file. He began to familiarize himself with Malik’s

criminal record, most of which he was able to recall because on two

occasions–one when he had been a detective sergeant, and the second, a newly

promoted inspector–he had been the arresting officer.