Causeway: A Passage From Innocence (38 page)

Read Causeway: A Passage From Innocence Online

Authors: Linden McIntyre

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography

“No,” I replied.

We were on the street when I remembered that Father Lewis had also lost his father suddenly and at an early age—just a year and a half ago. Jock was never sick. He went upstairs one day after lunch to take a nap. Shortly after that, Dolly, his wife, heard a thump. And, when she went to check, poor Jock was lying there on the floor.

There was a cold drizzle falling. Wellington Street was thick with cars. Important people were making their way home after another day running the country.

“I was just thinking about Jock,” I said. “How he went. I remember us talking about it afterwards, just after you moved up here.”

Lewis asked me where I was parked.

“Up behind the West Block,” I said.

We crossed the street in front of the National Press Building and climbed a short flight of stairs with black wrought-iron railings. The dark Parliament Buildings loomed like gargoyles.

“Give me the keys,” he said.

I dug them out and handed them over.

Near the car I stopped him, my friend the priest.

“I don’t recognize anything,” I said.

“Just lead the way,” he said. “I think that’s you over there.”

He was pointing towards my Beaumont.

“No,” I said. “I mean I don’t recognize any of the feelings. What

am I supposed to feel? What did you feel like, last fall, when they told you about Jock?”

“It’s okay,” he said. “It’s okay. We’re going to get you home.”

And I think the rain was coming down harder then. I think that it had suddenly become colder. And that we were in Ottawa on a Wednesday afternoon in March. And I think it was at that moment I realized, with a terrible finality, that Dan Rory MacIntyre was home where he belonged. A home where nothing ever changes. Back with his mother, the eternal Peigeag, for good.

And suddenly it hit me, on that rainy afternoon in Ottawa. The major difference between us was, despite the

buidseachd,

that he was luckier than I am.

He always knew where he was going, even when he didn’t have a clue how he might get there. Home—where Father Lewis says he’s taking me now. But here’s my problem—I’m not sure where home is anymore.

Late in 1969, seven months after my father’s sudden death, I gave up my job as Ottawa-based correspondent for the

Financial Times of Canada

and moved back to Cape Breton. I worked there for six years as resident correspondent for the

Chronicle Herald,

a daily newspaper based in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In those years I immersed myself in the life of the island. In my journalism, I reported aggressively on the industrial forces that were shaping and reshaping the life and culture of the place. I became active in a movement to restore and rehabilitate the Gaelic language, and I worked hard to achieve familiarity, if not fluency, in the language that was the key to unlocking so many mysteries in my personal history and communal past. I studied that history intensively; explored the long, rich memories of my elders; sought out and attempted to revive long-lost ties with distant relatives on the Hebridean island of South Uist.

I finally left Cape Breton again in 1976, somehow more secure in my identity. In 1980 I moved to Toronto, where I have now lived for more than twenty-five years.

In those later years I travelled widely in the world, carrying with me a profound curiosity about how we are altered by transient forces that, while appearing to be random and inevitable, are the consequences of ambition—another word for dreams. People dream, then seek the

means—the wealth, the might, the political consensus—to make their dreams reality. When they succeed, we call it progress.

I’ve learned how much of human history depends on the sanity of dreamers. And how much of reality is the product of delusions. And how progress doesn’t always mean improvement.

Each year I return to Cape Breton. Each year, it seems, the visits grow longer. But each year I leave again.

For many years I’d leave still wondering, as I wondered on that rainy afternoon in Ottawa in 1969: Where is home? Here? Where I’m going now? Where I get my mail?

Each visit to Cape Breton brings a common set of questions from my friends who never left there: When did you come home? How long will you be home this time? Doesn’t if feel great to be home again?

When I return to where I live and where I work, it seems I’ve gone away. Again.

I’ve spent years struggling to understand this phenomenon of identity—understanding who you are by knowing where you’re from.

I think I’ve come to terms at last with my dilemma. There is no answer because, essentially, there is no question. Where is home? Mere words, an admission of confusion from deep in the memory. When did you come home? It isn’t meant to be a question, but, basically, a statement of who they think I am. And I am comfortable with that.

The confusion of that sad, cold day in March 1969 eventually lifted. I have come to understand the insight best explored by the French ascetic and philosopher Simone Weil in her reflection on “The Need for Roots.” “Every human being needs to have multiple roots. It is necessary for him to draw well nigh the whole of his moral, intellectual and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he forms a natural part.”

I take all that to mean that roots are what we learn from everything around us, wherever we happen to be at any given moment. And that home is not so much a place as what we know, a concept that becomes our compass.

In the late sixties and early seventies, the economic boom, long predicted for the Strait of Canso, materialized with an expansion of the pulp and paper mill built by a Swedish multinational in the early sixties and by the construction of a new oil refinery, a heavy-water plant, and a supertanker docking terminal. The refinery and the heavy-water plant have since closed. Current expectations are that a long-awaited economic transformation will flow from the processing of natural gas from recent discoveries off the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia.

Cape Porcupine has become one of Canada’s largest stone and gravel quarries, producing, by the late nineties, two million metric tonnes of material annually for shipment throughout North America and the Caribbean. The quarry is owned and operated by a subsidiary of Martin Marietta Materials, the second-largest producer of industrial aggregates in the United States. Since the construction of the causeway, which required ten million tons of rock, Cape Porcupine has produced enough stone for several more causeways. The cape, today, looks battered, weary, depleted.

Optimistic predictions that Port Hawkesbury would become a city have not yet happened. The population of the town has, however, doubled, to about five thousand. The village of Port Hastings is now a bedroom community for several hundred people, most of whom

are employed in jobs that have been created since construction of the causeway in Port Hawkesbury and Point Tupper. One of the few recognizable parts of the old village today is St. David’s United Church. All traces of the old coal piers and wharf facilities are gone. The stores owned by Mr. Clough and Mr. McGowan are gone, as are the school, the railway station, Mr. Clough’s house, and the house I grew up in. The houses the MacIvers and Sylvia Reynolds lived in are gone, as are all the buildings on the water side of the road leading through the old part of the village. The house Mr. Malone built for his family, and the house Jackie Nicholson and his grandmother moved to in the village, are both vacant. Proposed changes in traffic flow at the various highway intersections in the village will mean further demolitions.

The railroad through Port Hastings and the bridge across the Canso Canal are now privately owned by Railamerica Inc., a U.S.-based company with close to fifty short-haul rail services in Canada and the United States. The rail line once used by the Judique Flyer—the train driven by Ian MacKinnon’s father and grandfather—has been abandoned and is now a recreation trail for hikers and all-terrain vehicles.

Jackie Nicholson died in an automobile accident in 1973 at the age of thirty-one. The historic lighthouse in which his grandmother laboured for many years, and which was destroyed during the causeway construction, has been replaced by a replica near the site of the original.

Ian MacKinnon—a lifelong teetotaller—retired after a long career with the Nova Scotia Liquor Commission. He is a stalwart in his church and chief of the community’s volunteer fire department.

Tae Man Chong, after a brief stay in his homeland, South Korea, returned to Canada in the late fifties, changed his name to Tae Di Yong, and established his own highly successful engineering business. He is now living, and still working, in a community north of Toronto.

In August 2005, on the initiative of the Port Hastings Historical Society, the last resting place of John Suto, which had never been

identified by a permanent grave marker, was relocated and restored. A new headstone records that he was a native of Hungary, that he worked at the Gorman camp during construction of the causeway, that he died on August 11, 1956, and was buried on August 13. At a small dedication service on August 8, 2005, the present parish priest, Father Bill Crispo, recalled and commended the brave and compassionate response to John Suto’s suicide by the late Father Michael “Spotty” MacLaughlin. John Suto and my father, whose lives were, oddly, symmetrical, are buried in the same cemetery.

Alice Donohue MacIntyre, who is my mother, and her sister, Veronica MacNeil, continue to reside independently in their own homes, with their political opinions and Hibernian sensibilities undiminished by time. They philosophically recall the days before the causeway when, it seems, all things were possible by strength of will and sinew.

There are now three MacIntyre households on MacIntyre’s Mountain.

The last Gaelic speaker on MacIntyre’s Mountain died in 2004.

On the headstone marking my grandparents’ graves, there is a Gaelic inscription: “An Cuid de Pháras dhaibh.”

It means: “May they have their share of Paradise.”

Ideas, interviews & features

Author Biography

L

INDEN

M

ACINTYRE

was born on May 29, 1943, in St. Lawrence, Newfoundland. His father, Dan R. MacIntyre, a hardrock miner, and his mother, Alice Donohue MacIntyre, a schoolteacher, were both natives of Cape Breton (MacIntyre’s Mountain and Bay St. Lawrence, respectively).

MacIntyre grew up in Port Hastings, Inverness County, Nova Scotia, where he attended local and county schools in the villages of Port Hastings and Judique. He earned a B.A. in 1964 from St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish after four years of studies there and at Saint Mary’s University and University of King’s College in Halifax.

From 1964 to 1967, he worked as a reporter for The Halifax Herald Limited, publishers of

The Chronicle Herald

and

The Mail-Star.

He spent most of that time as a parliamentary correspondent in Ottawa. Between 1967 and 1970, he was a reporter for the

The Financial Times of Canada,

also on Parliament Hill.

In 1970, he returned to Cape Breton following the sudden death of his father. He worked there as a correspondent for

The Chronicle Herald,

covering northeast Nova Scotia and provincial political affairs until he joined CBC Television in 1976. Based in Halifax, he worked for the CBC for three seasons, hosting a regional current affairs program called

The MacIntyre File.

In 1979, on behalf of his program and the CBC, MacIntyre successfully initiated a legal action to clarify public access rights to documentation regarding police search warrants. The case,

MacIntyre v. the Attorney General of Nova Scotia,

was eventually

heard by the Supreme Court of Canada and resulted in a landmark decision affirming press freedom and the principle of transparency in the courts.

Eventually, MacIntyre became an associate producer for the CBC television network. As a producer-journalist for CBC’s ground-breaking national current affairs program

The Journal,

he was assigned to documentary reporting in various parts of the world, including the Middle East, Central America, and the USSR. From 1990 to the present, he has worked as a co-host on CBC’s flagship investigative program

the fifth estate.

MacIntyre has won several Gordon Sinclair Awards for his work in journalism and broadcasting, as well as nine Gemini Awards from the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television. He has written and reported for numerous other award-winning projects, winning an International Emmy, a Canadian Association of Journalists Award, the Michener Award for meritorious public service in journalism, and several Anik Awards. He has also written and presented award-winning documentaries for PBS’s

Frontline.

MacIntyre holds an honorary Doctorate of Laws from University of King’s College, Halifax, and an honorary Doctorate of Letters from St. Thomas University, Fredericton.

MacIntyre’s first novel,

The Long Stretch

(1999), became a national bestseller and was shortlisted for the Dartmouth Book Award and the CBA Libris Book of the Year Award.

Causeway: A Passage from Innocence

(2006) was shortlisted for the Dartmouth Book Award and the OLA Evergreen Award. It won the Evelyn Richardson Prize for Non-fiction.

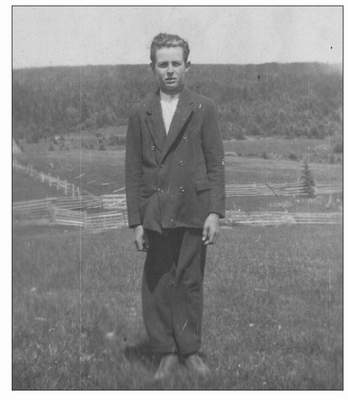

The MacIntyre Family Photo Album

Dan Rory MacIntyre, Linden’s father,

circa

1934, shortly before leaving home to work in the mines at age 16.