Causeway: A Passage From Innocence (39 page)

Read Causeway: A Passage From Innocence Online

Authors: Linden McIntyre

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography

Alice Donohue MacIntyre, Linden’s mother,

circa

1940.

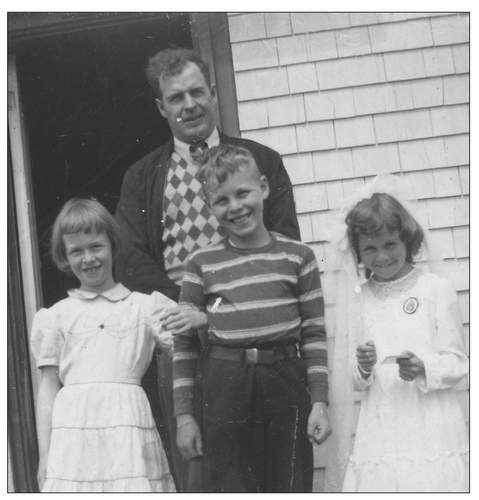

The MacIntyre siblings (from left: Danita, Linden, and Rosalind) with Dan Rory at the family’s home, 1953.

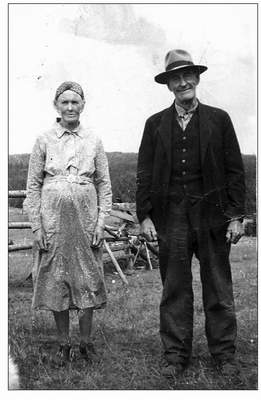

Dougald and Margaret (Peigeag) MacIntyre, Linden’s grandparents, on MacIntyre’s Mountain, 1944.

Alice, Sylvia, Ted, and Linden (age 14), ready for the prom, 1957.

Miners in East Malartic, Quebec, in the late thirties.

All photos courtesy of the author.

While writing

Causeway,

how were you affected, if at all, by controversies about the truthfulness—or lack thereof—of the memoir genre?

“My childhood unfolded in a kind of time warp.”

My first discussions about possibly writing a memoir took place in 2004. I’d become aware, over the years, of the fallout from some egregious literary lies.

The Hitler Diaries,

the notorious forgery of Hitler’s personal papers, stands out in my mind. Writing a memoir, particularly about a distant childhood, seemed to me to be a recipe for trouble. My instinct was dramatically confirmed by the uproar that resulted from James Frey’s pseudo-memoir,

A Million Little Pieces.

For most of my adult life, I’ve been conscious of the fact that my childhood unfolded in a kind of time warp. Chronologically, I grew up in the middle part of the twentieth century, but culturally—and in many respects materially—it was a much earlier time…possibly the late nineteenth century. This interesting anomaly of time and place was full of peril. Stories and books about where I grew up are all too often marred by quaintness, stereotypes, and exaggeration.

During a casual conversation about plans to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of the Canso Causeway, I felt a flash of inspiration. The causeway had been the focal point of our lives as a community during a crucial period of time. For my family, it offered a potential economic miracle. For me personally, it was an adventure that in many ways revealed a wider and more interesting world.

I decided to try to write a memoir conceived around the building of the causeway, and almost immediately I had to confront the challenges that have led writers with far greater skills into the murky waters of untruth. The impulse to indulge in self-mythology is powerful; the creative impulse to convert memory to art is ever-present; and, of course, there is the constant pulse-beat of urgency—the need to fill a page, to satisfy an editor, to get the monkey off your back.

“The impulse to indulge in self-mythology is powerful; the creative impulse to convert memory to art is ever-present.”

In the end, I applied fundamental rules: details were not invented; facts were not deemed as such unless credible sources were found to buttress memory; dialogue was, of necessity, invented and therefore was limited, and the circumstances in which dialogue occurred had to be factual. I have almost total recall of certain conversations with my father because the circumstances surrounding them were invariably unusual—as in the cases that I report of our two “man-to-man” talks when we lived together in mining camps.

I think the challenge of the memoirist was best captured by Nancy McCabe (after the

Flashlight Man,

2003), who observed that, during every moment of the process, the memoirist confronts questions about ethics and the boundaries of what’s true and fictional.

You’ve been a journalist for many years. Was that a help or a hindrance in what is, to a large extent, a creative exercise: reconstructing and reshaping distant memories?

A background in journalism was enormously helpful. The essential skill of journalism isn’t

writing. In fact, many good journalists are not good writers. A journalist’s fundamental skill is fact-finding and fact-checking. The defining quality of a good reporter is curiosity coupled with an instinct for communication. But it is the skill of tracking information sources that gives journalism its integrity. The same can be said of all non-fiction writing, but in the case of a memoir—where the subject is not a historically important individual—the challenge of finding factual support for the notoriously erratic memory can be daunting.

“The challenge of finding factual support for the notoriously erratic memory can be daunting.”

You’ve also written fiction. There are similar techniques in the writing of fiction and memoir. How does one employ the techniques of fiction without fictionalizing the memory?

Writing fiction is about imagining and developing characters, inventing plot, and shaping imagined people and circumstances into a coherent narrative that will inform, entertain, and—in the best cases—inspire. The memoir shapes real experience with real people into a story that reveals something that might have been hidden or was just not obvious to most of the people who shared it. Bringing characters to life on a page, be they imaginary or real, is difficult for most people. Storytelling techniques don’t necessarily come naturally to all of us.

I became interested in writing fiction because of a life-long fascination with the power of the imagination and the gift of using ordinary words and situations to convey extraordinary ideas. I grew up in a culture enriched by the oral traditions of storytelling and music. I think the discipline of journalism imposed some stringent controls on my writing. What might otherwise have been an exercise more in mystical creativity became one grounded in memory and research. In addition, I took the precaution of showing the unedited manuscript to relatives, including my mother.

“People who were once intimately familiar do become strangers, and this invariably comes as a surprise.”

People change over time. Obviously, revisiting your childhood required reconnecting with people from the past. How did this affect you and the story?

People who were once intimately familiar do become strangers, and this invariably comes as a surprise. Somehow we expect figures from our past to be as they have always been, frozen in memory. In reality, they are not. I found one exception to this often distressing fact of life. For many years, I had presumed that Ted, the young Korean man featured in

Causeway,

had returned to Korea and had made a life for himself there. To my surprise, he resurfaced in the mid-eighties, and I discovered he had been living in Toronto almost since the time he left Cape Breton. I met his family—his wife and two children. We socialized a bit, then lost touch again. Twenty years passed. While preparing

Causeway

for publication, I looked him up again. In 2006, I found him to be—as when we had first reconnected—virtually unchanged physically or in personality; he was still the funny and curious young engineer who had arrived in our village half a century earlier.

He remains a vigorous and athletic man with a bemused appreciation for a world he

knows well from his extensive travels. He remembers Cape Breton fondly. He and his wife, Sara, were able to correct some potentially embarrassing errors that arose from my flawed understanding of what he had originally told me about his early life in Korea.

Superstition plays a large role in the lives of many of your characters, some of them your close relatives. Are you superstitious? How do you regard superstition?

“No matter how informed we become, there will always be mysteries.”

Arrogant people tend to equate superstition with ignorance. I disagree with them. I believe superstition is a form of knowledge—a bridge between what we can know rationally and phenomena that we cannot possibly explain or even understand. Religious people call it “faith.” No matter how informed we become, there will always be mysteries. I personally witnessed at least one of my grandmother’s little “miracles.” Was it the result of some supernatural power? Coincidence? Mind over matter? I would be reluctant to discount her psychic ability—even now.

There is a moment in

Causeway when

you decide, with your mother’s help, against attending high school at a monastery. Where did you go, in the end?

The school in Port Hastings only offered up to grade ten. There was a high school a few miles away in Port Hawkesbury, but because our village was part of a rural municipality (Inverness County), I attended a consolidated school in Judique, another small community eighteen miles away. I still recall the culture shock of leaving a two-room school with maybe forty pupils for a new, much larger school teeming with about two hundred students.

“For many of my generation, personal history is shrouded in a language that exists only in fragments.”

At the end of

Causeway you

mention moving back to Cape Breton after the death of your father and reconnecting with your Gaelic roots. Why was this important to you at a time when your most direct links—grandfather, grandmother, and father—had been severed?

The death of a parent causes, along with the predictable grief, a great deal of introspection. In the aftermath of such a loss, I think most people become acutely conscious of their own mortality and, as a consequence, curious about identity and personal history. Our existence as part of a timeless biological community is our victory over extinction. So, following personal loss, we become anxious, and we seek to experience the reassuring reality of the people who have gone before us. For many of my generation, personal history is shrouded in a language that exists only in fragments. I thought this void represented a serious problem for the future—the potential loss of a heritage that is enriched by stories of personal courage, endurance, and survival in conditions of great hardship. A grasp of personal history reassures us of our abilities to rise above adversity, including death itself. The fragility of language, and the resulting vulnerability of our self-knowledge, alarmed and depressed me—and continues to do so.