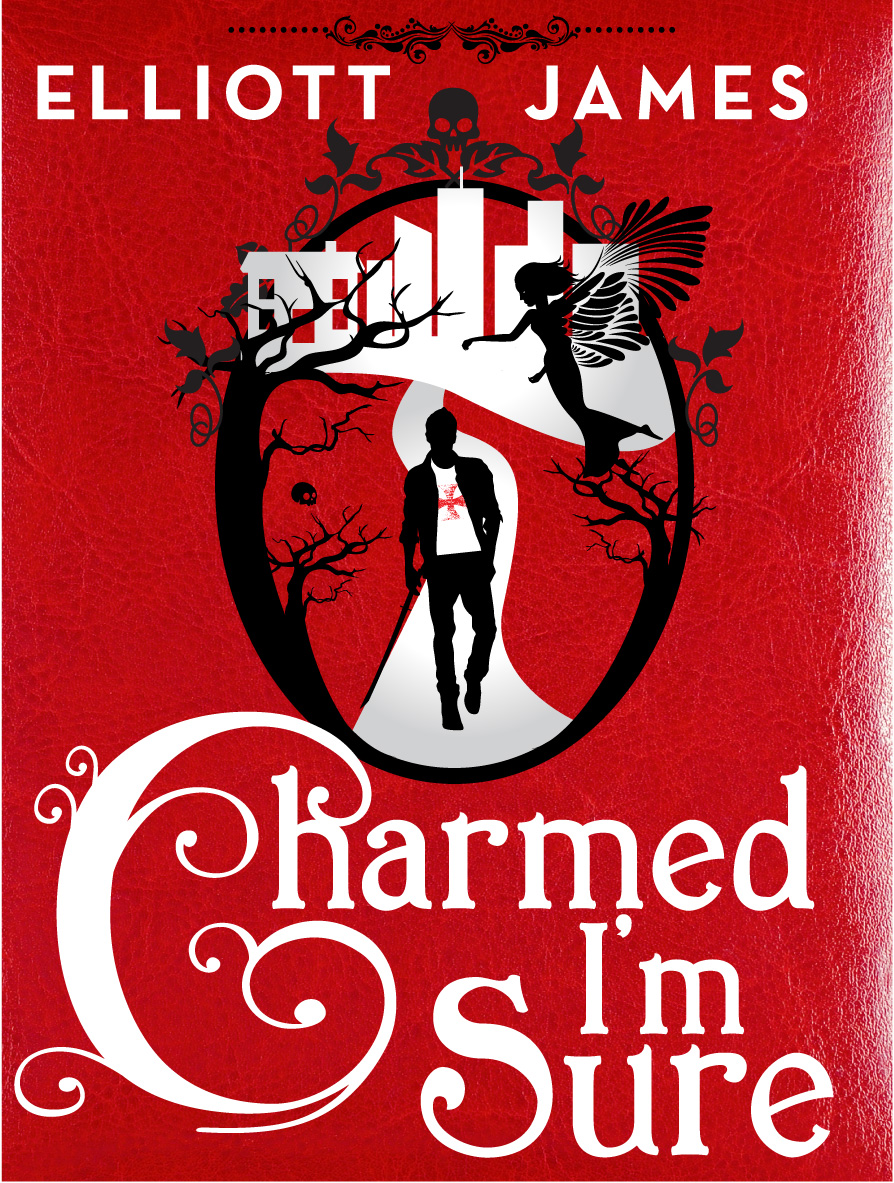

Charmed I'm Sure

Elliott James

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Once Upon a Time, a man wasn't wearing any clothes. It was one

A.M

., which is generally a pretty good time to be naked, but not if you're walking on the side of Route 44 outside Suckhole, Tennessee, or whatever the hell the name of the next town was. The man was middle-aged and white, the demographic most likely to be crazy or doing drugs, and he was moving in a halting way that suggested exhaustion and disorientation. I thought about just driving on, but not too seriously. I did mutter a few things that definitely weren't prayers under my breath while I turned around though.

When I pulled up on the wrong side of the road and stopped fifteen feet in front of him, the man raised his right hand to his eyes and stumbled to an uncertain halt. He looked filthy and emaciated in the glare of my headlights. His scraggly hair was the color of iron and hadn't been washed or brushed in days. His beard looked like it had never been groomed, period, though it wasn't up for a lifetime achievement award or anything, maybe a year in the growing. He didn't make a pretty picture. Robinson Crusoe's picture maybe, if Robinson Crusoe had had a Facebook profile. Still, it could have been worse. The only parts of him that were obviously bleeding were his feet.

I pulled the lever that unlocked the trunk of my car and slowly opened the front door, keeping it between us as I got out. On the surface of things, I was being ridiculous. Even if the man had been in prime condition, I had about five inches and seventy pounds on him. But I've never put much faith in the surface of things.

His eyes were taking longer to adjust than they should have, as if he hadn't seen light in a long time. It was May in the Great Smoky Mountains and bugs had to be eating him alive, but he didn't seem to notice.

“Do you have any identification?” I asked.

No, just kidding. What I really said, very slowly and clearly, was: “Is anyone chasing you?”

“Iâ¦no?” His voice was painfully dry, but he managed to sound both indignant and frightened at the idea.

“Are you hurt?” I asked.

“I hurt all over.” He stated this like a child complaining of a sick stomach: unembarrassed by his nudity, small voiced and blinking, considering his answer gravely but without any drama.

“What happened to you?”

“Damned if I know,” he said petulantly.

I nodded. “Would you like me to get you some water and clothes out of the trunk of my car?”

“I'd like some water,” he rasped. After another few seconds he added, “And clothes.”

“Okay,” I said. “Hold on.” I had recently been forced to leave my home in Alaska and was traveling between random locations while I looked for a new place to settle down. Accordingly, my car trunk was crammed full of odds and ends. I found him some running shorts and a T-shirt and a towel and a first aid kit and a big plastic jug of water. By the time I brought them to him, I also had a fourteen-inch knife on my hip.

There was no wind, and the air was as hot and heavy as a giant dog's breath, so I had to get close to smell him. When I did, I was hit by a wave of odors: river mud and blood and body musk and sex funk and a faint scent of something else on top of that, something that was coming off him but not from him. The closest I can come to describing the aroma is honeysuckle and milk.

“Drink it slowly,” I said, handing him the big plastic jug.

He ignored me and sucked at the container greedily, his cheeks working like bellows. Within a few moments he was spewing water back up, coughing and holding his palm over his mouth in a vain attempt to keep it all in. After that he sipped more sparingly.

I made him put on the shorts before I opened the first aid kit. He had a lot of scratches and rashes and bruises and scrapes and small puncture wounds where thorns had grabbed hold of him, but I didn't see any large bites or obvious bone breaks. There were a lot of scars on his back. Evenly spaced, they looked like they had been left behind by long fingernailsâthe sheer number and various degrees of healing suggested rough sex or rape scars made by a woman or women who had been beneath him repeatedly.

I had a hard time picturing him holding someone else in captivity. He was probably suffering from starvation and malnourishment.

Mostly, though, the thing that was really messed up about him, at least on that surface of things that I don't trust, were those feet. The more I cleaned them, the worse they looked. The feet hadn't just been cut, they had beenâ¦eroded.

We talked a little more. He sat sideways in the passenger seat of my car, his feet dangling out the open doorway while I cleaned and bandaged them. He seemed to be focusing a little better. When another car drove by and some idiot yelled “Faggots” out a window, he grimaced and muttered something about jackasses under his breath.

“What's your name?” I asked.

“Dustin Seavers,” he said automatically. “What's yours?”

“Tom Morris,” I lied. The last thing I wanted was my current alias popping up on some police report later. It really would have been smart to keep on driving. Unfortunately, I'm not any better at being smart than I am at being trusting. It's an awkward combination. “Are you from around here?”

He looked around him then as if seeing his surroundings for the first time. His voice was mildly alarmed. “I don't think so. Where's the snow? How far are we from Hershey?”

I focused on him, shutting out the background noise until I could hear his heartbeat. It was too fast, but it was steady. “Do you mean Hershey, Pennsylvania?”

He swore then. “Am I across the state line?”

“You're across a lot of state lines, Dustin,” I informed him bluntly. “We're in Tennessee.”

He tried to jump to his feet and I pushed him back down in the seat easily. The moment my palm touched his chest he went still, though he didn't stop cursing. It reminded me of a horseâthe way they'll still at your touch, but you can still feel their muscles trembling beneath your hand.

“Settle down. I'm not bandaging up your feet twice,” I told him.

The lack of sympathy seemed to calm him.

“What's the last thing you remember, Dustin?” I kept my voice even.

“I don't know,” he groaned. “I was at the cabin.”

“In Hershey?” I prodded.

“Between Hershey and Gettysburg,” he elaborated. “It's family land. I wanted to spend a few days there just in case.”

That sounded promising. “In case of what?”

He looked at me like I was an idiot. “You know. Y2K, man. The Millennium Bug.”

I've had a lot of practice not looking surprised. “You're talking about the big Internet panic? People scared of computers crashing and taking down civilization in the year 2000?”

He was getting angry now. “Yeah. Where have you been?”

The anger was what made me decide to go ahead and tell him. If he had to get a good meltdown out of his system, I could choke him out pretty easily if I had to, and I wouldn't have to use a Taser or sedatives or pepper spray or a nightstick to do it. I wouldn't use it as an excuse to lock him away in a cell where he could become somebody else's problem either, the first stop in a long series of temporary confinements, bureaucrats, and checked boxes until Dustin wound up in some institutional version of the “Island of Misfit Toys.”

Sorry. I have some authority issues.

“It's not 1999 anymore, Dustin,” I told him. “That was a long time ago.”

At first he was silent. Then his cursing became more inventive. Dustin used one particular word as a noun, verb, and adjective, which is always good for bonus points. I think he would have stormed up out of the car seat if he hadn't still been slightly afraid of me.

There was a copy of the paper that I had bought in Oklahoma City still folded in the footwell of my back seat. I wordlessly got it and let him look at the date. It was too much for him. Dustin didn't scream or run off or try to attack me; he didn't seem to hear or see me at all any more, just rocked his head back and forth slightly.

Okay, maybe I should have let someone with lots of letters after their name and access to Thorazine deal with Dustin after all. Oops.

I looked around, studying the area so that I could find my way back. If I'd had a cell phone with a GPS application, I could have marked the location by satellite, but I didn't have any cell phone at all. It's too easy to track someone who has one of those things, and even if it weren't, cell phones scare the bejeezus out of me. I've been around enough evil magic to know that there are some things you can possess and some things that can possess you.

It was only while I was checking for distinctive landmarks that I saw the shrubs lined up on the side of the road. They were hawthorn trees. That wasn't a good sign.

*Â Â *Â Â *

A little over an hour later I was back. I had dropped Dustin at a truck stop three exits away. He was still shaky but halfway lucid again and talking about a brother and an ex-wife by the time we got there. I gave him a phone card and enough money to buy a few meals. If he couldn't find his way to the help he needed from there, well, I had problems of my own.

I was wearing a camouflage jacket by this point, carrying an ax in my hand and a compound bow and quiver across my shoulders. A Ruger Blackhawk was holstered at the small of my back and the knife was still on my hip, along with a waterproof belt that had several pouches.

It didn't take me long to find Dustin Seavers's scent. I followed it along the side of the road, and I only had to step off into the woods three times, twice to avoid headlights and once to use the ax. I cut a straight, sturdy-looking branch from a hawthorn tree. Separating the branch from the trunk was easyâI'm stronger than I have any right to be, and I'm intimately familiar with the use of an axâbut stripping the branch down to a crude sturdy pike and sharpening both ends was still a pain in the ax, so to speak. I went ahead and made a stake out of a smaller branch while I was at it, poking two holes in the interior lining of my jacket where it fell loose at my left side and threading the stake through them.

And no, I wasn't hunting vampires.

When the Fae visited our realm in great numbers thousands of years ago, they didn't just materialize like someone on a transport or teleport beam in one of those science fiction movies; the copses and glens and glades where they performed their traveling spells came with them, and some of the vegetation that they introduced to our soil flourished. This is how the word

elder

got in

elderberry

and why

holly

and

holy

used to be synonyms. Hawthorn trees are another example, and places of power where the Fae perform their ceremonies are often marked by an abundance of them.

It's why people used to believe that taking anything from a hawthorn tree into your house was bad luck.

I left the ax by the tree and picked up my crude pike in its place. After about a mile and a half, I found the place where Dustin Seavers had emerged from the woods.

The ground was dry and the stars were out and Dustin's scent was still strong. He hadn't washed with anything but river water in a very long time, and I might have been able to catch his scent even with normal senses.

I heard the sound of distant gunfire popping through the trees. Not single shots like a hunting rifle, but rapid staccato shots like a string of firecrackers going off. Somebody had an automatic weapon out there in the woods. After about fifteen seconds there was another round of gunfire, and then another round fifteen seconds after that. Probing shots or herding shots. I moved faster.

Eventually I came to an opening in the forest that made me pause. In the center of the glade was a ring of flesh-colored mushrooms, perhaps twenty feet in diameter.

A faery ring.

Gripping the crude hawthorn pike in both hands, I began to jog around the faery ring in the same direction that the sun travels. Some folklore says that for the counter-charm to work, you have to run, but that's just a confusion of cause and effect. People who knew what they were doing used to run around faery rings for the same reason I was running now, because they wanted to get the hell out of there as fast as possible. As I finished my ninth circuit, an outline began to shimmer and then became visible. There were a man and a motorcycle in the center of the ring.

The man was kneeling, as naked as Dustin had been except for some kind of sports watch. His butt was resting on the backs of his legs, and his hands were flat on his upper thighs. His body was motionless except for the slight heaving of his chest. He was in much better shape than Dustin Seavers had been, younger and well-muscled, his blond hair cut to military shortness. The tattoo on his upper left arm declared him a Marine.

The man didn't register my presence. His eyes remained half-lidded, his breathing rapid and shallow.

Tranced.

The motorcycle next to him was a Harley, one of the pre-1980 models from before the company started making the bike prettier. Painted black with spider-web designs traveling over its body, the bike glistened. I looked at it more closely. It wasn't just the paint jobâthe parts looked brand-new, and some of them weren't being manufactured anymore.

I was careful not to step into the faery ring while I studied its inhabitants. The Fae departed this realm a long time ago, but they left all kinds of half-breed bastards and magical experiments and cursed beings behind them when they went. These cast-offs can't follow the Fae all the way home, but there are still in-between places that some of them can travel through, splices in reality that play merry hell with time and space. The laws of physics are more like habits, really, and legends about people stepping into faery rings and becoming invisible and intangible to other humans are not uncommon.