Chatham Dockyard (32 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

The years immediately following the end of the First World War were the post-war years, a difficult time for the dockyard. Previously issued orders for the construction of new ships that had not yet been laid down were immediately cancelled, while work on

Warren

, a W-class destroyer under construction, was suspended. This, the only destroyer ever to have been ordered for construction at Chatham, was never completed, being scrapped in 1919. At the same time the Navy was also being run down and the river Medway was crammed with ships being paid off. The numerous creeks were filled with unwanted torpedo boats, while destroyers and cruisers were anchored in mid-river positions, awaiting delivery to the breakers yard.

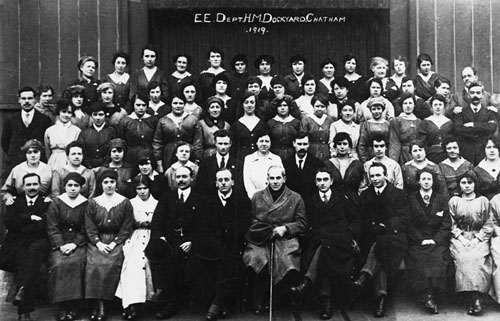

Members of the dockyard’s Electrical Engineering Department pose for a photograph that was taken in 1919. A number of women are among those employed in this area of the dockyard but would soon be made redundant. It had only been a temporary wartime policy to bring women into a number of additional areas of dockyard work (over and above the colour loft and ropery) for the purpose of releasing men to enlist.

To provide some work, the yard labour force was employed upon completing a number of partially finished ships. These were vessels originally launched in private yards but having no engines or other equipment. In 1922 the cruisers

Enterprise

and

Despatch

came to the yard, as did the W-class destroyer

Whitehall

. The submarines

L23, L53

and

K26

were also fitted out at Chatham, while the submarines

K24, K25

and

K28

were to have been brought to Chatham, but were scrapped instead.

Many of the passing events of that period were recorded by Cyril Cate, a dockyard electrician who, from 1916 onwards, had begun keeping a regular diary of passing events. As with many employed in the dockyard, he came from a family totally immersed in dockyard matters, his father having been a shipwright while his sister Emily had joined the yard’s Torpedo Department in 1916. Launchings, in particular, were well recorded in the pages of his diary, with one of the earliest that he mentions being

Kent

, a County class cruiser launched from the No.8 Slip in March 1926:

I went to No.8 Slip and saw launched successfully HMS

Kent

by Lady Stanhope. Public allowed and crowds of people attended …

Kent

in the North Lock (for purposes of entering the fitting-out basin) by about 3.30 in the afternoon.

Launchings of vessels did not always go as smoothly as this one had done, with Cate adding this note to his diary on 23 September 1923:

Submarine O1 or Oberon to be launched but after the ceremony was performed and all was ready two blocks aft were found to be too firm to move and tide came in and hindered work of removal. Launch postponed [until the following day].

A large number of more general activities within the yard are also recorded within the diaries. In September 1926 he refers to the demolition of a dockyard hoist (known as sheer legs because of their similarity to a pair of shears) that had once been used for the fitting out of ships’ engines:

[Saturday 4 September] Sheer legs on No.2 Basin were demolished. They are forty years old and condemned as unsafe. All ships were cleared from [the] basin and at 12.30 a charge fixed to lower part of back leg was exploded and the legs allowed to fall into water.

Moving a few years forward, Cyril gives a series of daily reports on the success of the annual Navy Week held by the dockyard during the summer of 1929. On the first day, Monday 12 August, Cyril indicates ‘a good number of people to have been present’. As for himself, he was quite fascinated by the event. That evening he was at Wigmore where his father owned land which the family used for playing tennis. While there, he spent some time watching ‘all the visitors’ to the dockyard making their way home. On the following day he must himself have given the impression of being one of the

exhibits on display. Helpfully reinforcing the public notion that yard workers rarely exerted themselves, he spent the entire day ‘sitting on the foc’sle of [HMS]

Hawkins

’. For the rest of the week he continued to comment on the immense numbers visiting warships open to the public. On the Saturday, however, he rather reversed the situation. Instead of entering the yard as a worker, he joined the visiting public and boarded a number of the vessels.

Kent

, launched on 16 March 1926, was the largest cruiser to be built at Chatham. Of particular importance was that the order to build this vessel came at a time when many dockyard workers were being laid off, so ensuring that some of those who may well have lost their jobs in the yard were given a few years of respite.

Elsewhere in the diaries, numerous references are found to the various ships upon which Cyril was working. In 1919 alone he records the names of eleven separate vessels, these including destroyers, cruisers, a small monitor and a troop ship. As a rule, any vessel upon which he was working would be moored in the fitting-out basin. However, this was not always the case. Sometimes the vessel had already left the dockyard, with urgent electrical work having to be undertaken while the vessel was in the Medway or even lying off Sheerness. On one occasion in 1926 he was working on a vessel while it was in the process of leaving the yard. This was

Centurion

, a former battleship that had been converted into a target ship. On 16 August this entry appears, ‘our boat

Centurion

placed in North Lock in morning and left at 3.45 for Sheerness.’ On the following day he made a further reference to this vessel, ‘caught the “

Advice

” [a dockyard paddle tug] in morning at 7.15 and went to “

Centurion

”. Worked on fire pump and got back to locks at 3.30.’

As with the vast majority of the population, the coming of war in 1939 proved something of a watershed in Cyril’s life. The number of hours he was expected to work dramatically increased while Winnie (whom he had married in 1930) together with Sylvia (their five-year-old daughter) and Derek (a son of three months) were evacuated to Sellindge. On Saturday 3 September, the day war broke out, he noted ‘war commenced with Germany at 11 a.m. I had to work until 7’. This, in itself, broke a carefully established routine. Cyril was a committed Christian, a member of the Plymouth Brethren, who always made a point of attending Sunday service at the Gospel Hall in Gillingham’s Skinner Street. In addition to this, he was a Sunday school teacher. Having to enter the yard on Sunday and return to an empty home (for his family had been evacuated on the previous day) must have been an extremely unsettling experience. Nor could matters have been helped by the alien environment of a blacked-out Gillingham. He had already confided to his diary on 1 September, that the entire Medway Towns were under ‘complete black out at night’ adding that ‘sandbags were everywhere’. To this he added a few days later, ‘everywhere looking warlike’. As for the dockyard, ‘[4 September 1939] Maidstone and District buses in yard being converted to ambulances. Police patrolling sheds with metal helmets’.

That the dockyard did not succumb to aerial bombardment, although it underwent numerous attacks, was more by luck than judgement. Easily located from the air and within short flying time from the Continent, it seems surprising that Chatham, when compared with the yards at Portsmouth and Plymouth, received relatively small amounts of damage. Nevertheless, lives were lost and a number of structures were destroyed. In late 1940, the Factory, a large building which housed the engine fitters

and lay alongside the No.1 Basin, received a direct hit, this resulting in the loss of twenty-three lives. On later occasions, both the smithery and saw mill were to be bombed. One incident often recalled by those who worked in the yard during those years is that of

Arethusa

, while in dry dock, using her 4in anti-aircraft guns against bombers seen to be approaching London. Reminiscent of the actions taken by

Erebus

some twenty-three years earlier, a curtain of exploding shells proceeded to force many of these bombers to alter course. If nothing else, it raised the morale of those working in the dockyard.

With its workforce brought up to 13,000, of whom 2,000 were women, the output in these years even exceeded that of the First World War. In all, twelve submarines, four sloops and two floating docks were laid down during these years, while 1,360 refits were carried out. Additionally, the dockyard supplied stud welding equipment for tanks and other fighting vehicles, fitted out over 1,200 shore establishments and, in December 1944, supplied and started a shore carrier service to naval bases and parties on the continent. A number of two-man submarines were built at Chatham, fitted with lorry diesel engines and dustbin-like torpedo tubes. Of the larger refits, the cruiser

London

was plated with armour and

Scylla

was converted to an escort carrier flagship. The final months of the war also saw Chatham busily engaged in fitting out part of a fleet destined for the Far East and the continuing war against Japan.

For those employed in the dockyard during the Second World War, a particular fear, and on a par with being caught in an air raid, was that of post-war Britain turning against those who had secured the victory. Reflecting on the years that followed the ending of the First World War, they remembered how numbers employed in the yard had been mercilessly slashed, with thousands forced out of the yard to fend for themselves as best they might. Some, indeed, saw it as not unlikely that the dockyard, upon the ending of the war against the Axis powers, might even be closed. After all, both Pembroke and Haulbowline had suffered this fate immediately after the First World War, although the former had been reopened upon the outbreak of the Second World War. As it happens, nearby Sheerness was certainly closed, although not until 1956, with the temporarily reopened Pembroke also finally abandoned. Chatham, however, avoided the dreaded axe, successive Conservative candidates in seeking out the dockyard vote promised that only with that party in power would the dockyard be secure. Of course, the irony was that under Margaret Thatcher, the ‘Iron Lady’ of the Conservative party, the yard was finally closed. In the meantime, Chatham remained open, seemingly defying the odds, but bringing a degree of prosperity to an area of Kent that was entirely dependent upon this one major employer. Life in the Medway Towns, apart from those who commuted to London or in some other way were insulated from their neighbours, was the naval dockyard.

10

In the years that immediately followed the Second World War, Chatham dockyard hit the news headlines on two occasions, but for completely the wrong reasons. It resulted from two dramatic accidents that took the lives of a number of those employed in the dockyard. The first of these occurred during the afternoon of 14 January 1950. In the Thames estuary,

Truculent

, a submarine returning to Chatham following successful sea trials, collided with the SS

Divinia

, a 640-ton Swedish tanker. As well as her normal crew of sixty-one, the submarine also had on board eighteen dockyard workers who had been monitoring her machinery during that final day of her sea trials. While

Divinia

suffered relatively little damage, the submarine was badly holed and immediately began to sink. While those on the bridge were thrown into the sea, those below were able to make the vessel watertight aft of the Control Room with many later exiting through the aft escape hatch. Tragically, in the darkness, most were swept away by the tide and died of either hypothermia or drowning. In all, only fifteen survived, the tragedy taking the lives of forty-nine sailors and fifteen dockyard men who had been on board.

1