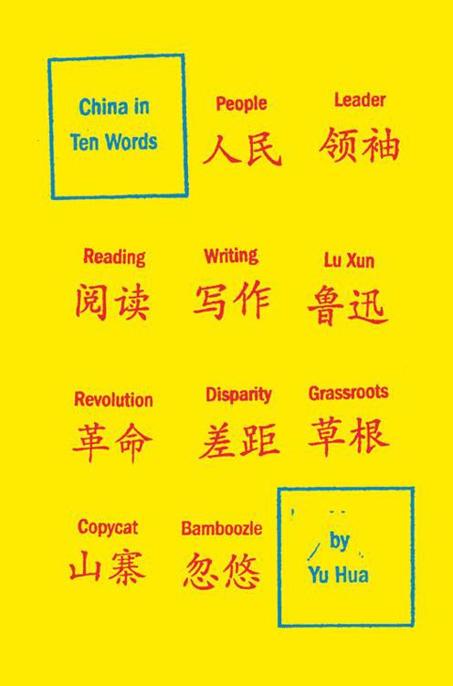

China in Ten Words (26 page)

Read China in Ten Words Online

Authors: Yu Hua

Tags: #History, #Asia, #China, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Political Science, #Globalization

As time went on I resorted to ruses and subterfuges even more often, no longer feigning illness simply to deflect punishment but also to get out of household chores like sweeping or mopping the floor. Once, however, I was too smart for my own good. When I announced that I had a stomachache, my father clapped his hand on a spot in my midriff. “Is this where it hurts?” he asked. I nodded. “Did the pain start higher up, here in the pit of your stomach?” he asked. Again I nodded. My father continued his line of questioning, trying to establish whether my symptoms corresponded with those of appendicitis, and I simply kept nodding to his every question. Actually, by this point I couldn’t tell whether it really hurt or not; it just seemed to me that I felt a pain wherever my father’s strong hand pressed, just as surely as I would answer whenever he called my name.

Next thing I knew, my father was carrying me piggyback out the door. I lay slumped over his shoulders, disconcerted by this turn of events and utterly in the dark as to what was going to happen next. It was not until my father entered the hospital surgery that I realized things were not looking at all good. At that point I was in a welter of confusion: my father’s look of determination made me feel that I perhaps did have appendicitis, but I was aware that when it all started I was just pretending to be in pain, even if it really did feel a bit sore later when my father’s probing hand was pressing down on me. My head was spinning; I had no idea what to do. As my father laid me on the operating table, I managed only a feeble demurral. “It doesn’t hurt anymore,” I said.

He pinned me down on the operating table, and two nurses fastened my hands and feet with leather grips. Now I began frantically to resist. “It doesn’t hurt anymore!” I yelled.

I was hoping they would abort the operation that now seemed imminent, but they paid me not the slightest attention. “I want to go home!” I cried. “Let me go home!”

My mother, the head nurse in surgery at the time, placed a piece of cloth over my face. Through the opening in it I issued a piercing scream, reiterating my objection to surgery. Since my hands and feet were tied down, I could only twist my body back and forth to underscore my refusal. Somewhere above I heard my mother’s voice: she was telling me not to shout, warning me I could choke to death if I didn’t stop. This frightened me, for I didn’t understand how shouting could kill me. No sooner did I stop to ponder this question than I felt the spurt of a pungent anesthetic in my mouth, and I quickly lost consciousness.

When I came to, I was lying on my bed at home. I felt my brother stick his head under my sheet and immediately remove it. “He farted,” I heard him yell. “Oh, what an awful stink!” Soon my parents were standing by my bed, chuckling. My appendix had been removed, and the gas I discharged in my semicomatose state signaled the success of the operation and confirmed that I would make a quick recovery.

Many years later I asked my father if, when he opened me up and saw my appendix, it really needed to be removed. “Oh, absolutely,” he said. What interested me, of course, was whether my appendix had actually been inflamed or not. But on this point my father’s answer was ambiguous: “It did look a little puffy.”

“What does that mean?” I wondered. My father admitted that a little puffiness might well have cleared up by itself, even without medication, but at the same time he insisted that surgery had been the best option, because medical opinion at the time held that not only appendixes that looked “a little puffy” should be removed but even completely healthy appendixes ought to go.

I used to think my father was right, but now I see things differently: I think it was a case of reaping what one sows. I had originally been bent on bamboozling my father, but in the end I simply bamboozled myself onto the operating table and under the knife.

*

huyou

About the Author

Yu Hua was born in 1960 in Zhejiang, China. He is the author of four novels, six collections of stories, and three collections of essays. His work has been translated into more than twenty languages. In 2002 he became the first Chinese writer to win the James Joyce Award. His novel

Brothers

was shortlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize and awarded France’s Prix Courrier International in 2008,

To Live

was awarded Italy’s Premio Grinzane Cavour in 1998, and

To Live

and

Chronicle of a Blood Merchant

were ranked among the ten most influential books in China in the 1990s by

Wen Hui Bao

, the largest newspaper in Shanghai. Yu Hua lives in Beijing.

About the Translator

Allan H. Barr is the translator of Yu Hua’s debut novel,

Cries in the Drizzle

. He teaches Chinese at Pomona College in California.

Also Available in eBook Format

Brothers •

978-0-307-37798-2

Chronicle of a Blood Merchant

• 978-0-307-42526-3

Cries in the Drizzle •

978-0-307-48340-9

To Live

• 978-0-307-42979-7

More info @:

http://www.pantheonbooks.com

Follow:

http://twitter.com/pantheonbooks

Friend:

http://facebook.com/pantheonbooks