Chinese Cinderella (12 page)

Read Chinese Cinderella Online

Authors: Adeline Yen Mah

I squatted in the corner farthest from Jackie’s doghouse and dug away with an old iron spoon which Cook had discarded, wishing I had a spade. I kept one wary eye on Jackie, who was lying half in and half out of his dog‐house, watching me. His mouth was open and he was panting with his large tongue hanging out between two rows of giant, sharp teeth. Just as I knew PLT was my friend, I was equally certain Jackie was not. He would probably attack me if I rubbed him the wrong way. I glanced at the large, wolf‐like dog and shivered involuntarily.

Soon I came upon a worm. I freed it from the clumps of weeds, wet leaves and mud and placed it in a paper bag. PLT would be pleased. Everything smelt sweet, fresh and damp. Jackie had not stirred. His eyes were half closed, and he was breathing regularly, about to fall asleep. I tiptoed away so as not to wake him and ran upstairs directly to the duck pen on the roof terrace.

All seven ducklings scampered around to greet me joyously. Though the maids were supposed to feed them and sweep out the pen, they didn’t relish the task and often neglected it. I noticed the food bowl and water pan were both empty. Since I was eager to give PLT her treat, I decided to alert the maids later.

I knelt and placed my worm in the food bowl. The entire flock crowded around, jockeying for position. Though they looked identical to the grown‐ups, each was distinct and unique to us children. I was pleased to note that PLT had grown quite big and strong and was holding her own against the rest. The ducklings of Little Sister and Second Brother were aggressively jostling PLT. I tried gently to shoo them away so PLT could eat her worm in peace. I felt quite guilty about my favouritism and couldn’t help blaming myself for not having procured more worms so each duckling could have its own.

Suddenly, I felt a painful blow against the back of my head. It was so hard I was knocked sideways to the ground. The ducklings scurried off in fright. I looked up to see Second Brother scowling down, arms akimbo. Apparently, he had been watching me stealthily from the landing for some time. ‘This will teach you to favour

your

duck over

mine

!’ he shouted. He hit me again, picked up the food bowl and ordered me to ‘

get lost!

’ as he fed my worm to his own duckling.

I got up and turned to go. It was then that I noticed PLT. Unlike the rest, my pet had not run away but was standing faithfully by my side. Despite the pain and commotion caused by my brother’s blows I found immense consolation in the knowledge that PLT was staying right by me. I picked up my bird lovingly and for a moment seemed to see my grief reflected in her round dark eyes.

Back in my room I busied myself getting some grains of rice and water for PLT. It was still early and Aunt Baba hadn’t come home from the bank. PLT waddled about, busily pecking the floor, now and then coming over to look at me. ‘Apart from Aunt Baba, you’re the only one who’s always here for me; the only one who understands. Are you reminding me that I promised you a tasty worm yesterday?’ I asked in the coaxing tone I reserved for my pet. PLT looked back wistfully with her round eyes, which resembled two black gum‐drops. I felt sure she understood every word. ‘I bet you wish you could talk and tell me all sorts of things,’ I said to my pet. ‘Though Second Brother robbed you of your worm, it’s not the end of the world. I’ll just have to go downstairs and get you another. Wait here!’

I returned to the garden. Jackie was now wide awake and pacing the ground aggressively. Back and forth. Back and forth. He had awakened from his nap in a bad mood and was growling at me. With his long, pointed ears, triangular eyes, prominent jaws and sharp teeth, he resembled a ferocious wolf more than ever. I was quite fearful as I started to dig up a patch of earth at the foot of the magnolia tree.

Jackie fidgeted, pawed the ground, and started to bark at me. I could see the tail end of a worm burrowing rapidly beneath a clump of roots. Though I knew I had incurred Jackie’s displeasure in some way, I was reluctant to leave empty‐handed. Keeping one eye on the worm, I half turned towards Jackie, who was baring his teeth in a most menacing manner. Tentatively, I stretched out my left hand to calm him while clutching the spoon in my right. Suddenly, Jackie lunged at me and sank his teeth into my outstretched left wrist.

Abandoning my spoon, I hurried away. PLT greeted me expectantly at the door but I rushed past into the bathroom to wash away the blood trickling down my left arm. Footsteps sounded from the landing. Aunt Baba had finally come home from the bank.

‘What happened to you?’ she asked in alarm, and something in her voice made the tears well up in my eyes. Baba hurried over and held out her arms, rocked me back and forth, dried my tears and asked, ‘Are you hurt? Is it bad?’ She wiped away the blood, washed my wrist, dressed the wound with mercurochrome, cotton‐wool and a small bandage. She then walked over and locked our bedroom door, followed and watched by PLT every step of the way. She seated me on my bed and smoothed my hair. ‘It’s better not to mention any of this at dinner tonight unless you are asked directly,’ she advised. ‘Jackie is

their

pet. Don’t make any waves. I tell you what. Let’s open my safe‐deposit box and take a look. That’ll make us both feel much better.’

Aunt Baba rummaged through a pile of folded towels in her cupboard, underneath which she had hidden her safe‐deposit box. She unlocked it with the key on the gold chain she wore around her neck. This was where she kept her scanty collection of precious jewels, some American dollar bills, a sheaf of yellowed letters, and all my report cards, from kindergarten to the most recent.

We gazed first at those reports written in French from St Joseph’s kindergarten in Tianjin; then the ones for the first and second grades written in Chinese from Sheng Xin Primary School in Shanghai. Even PLT stopped her wandering to sit contentedly at our feet, looking up occasionally as if wishing to participate.

‘See this one?’ Aunt Baba exclaimed with pride. ‘Six years old, all of first grade and already tops in Chinese, English and arithmetic. At this rate nobody going to university can have a better foundation. When you get to be twelve you should sit for the examination to enter McTyeire where your Grand Aunt went. Then go on to university. You can be anything you set your mind to be. Why, you might even become the president of your own bank one day!’

‘Will you come and live with me if I’m president?’ I asked wistfully. ‘I wouldn’t want to own a bank without you.’

‘Of course I will! We’ll set up house on our own and take PLT with us. We’ll work together in our own bank, side by side. Mark my words, if you study hard, anything is possible!’

‘I will study hard! I promise!’

The truth was that as soon as I heard Aunt Baba’s footsteps, I started feeling better immediately. Knowing there was someone who cared for and believed in me had revived my spirit. So we chattered happily about this and that until dinner‐time.

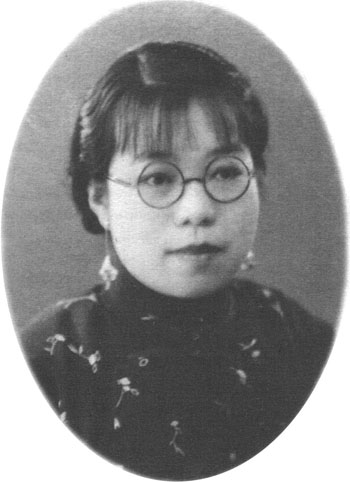

G

RAND

A

UNT

She was also known as Grand Uncle: Gong Gong because of the respect granted her as president of the Shanghai Women’s Bank, which she founded in 1924.

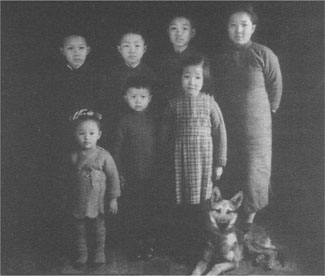

T

HE SEVEN OF US WITH

J

ACKIE

This picture was taken in 1946, about the time that we were given a little duckling as a pet. I was eight years old.

N

IANG

, Y

E

Y

E AND

F

ATHER

Ye Ye was a devout Buddhist. He always shaved his head, wore a skullcap in winter, and dressed in Chinese robes.

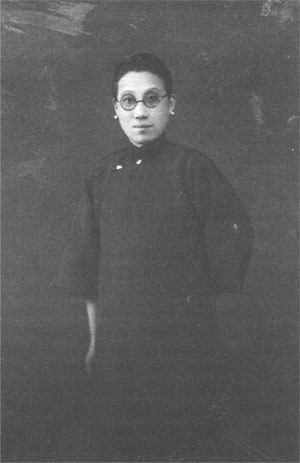

A

UNT

B

ABA

This photograph was taken in the 1930s. Aunt Baba never married and was financially dependent on my father and stepmother all her life. I loved her very much.

The breeze died down and it became very warm as the evening meal progressed. As usual, all the dishes were served at once: cold cucumber chunks marinated in vinegar and sugar; tofu with minced pork and chopped peanuts; sautéed shrimp with fresh green peas; steamed stuffed winter melon; sweet‐and‐sour pork with pineapple slices; stewed duck with leeks. After the grown‐ups were served, we children were each handed a bowl of steamed rice and an assortment of the day’s dishes. We were expected to consume every morsel of food on our plates. It was frowned upon to leave any scraps behind, even one grain of rice.

Ever since the arrival of PLT, I had started to hate eating duck in any form or shape. It seemed wrong to eat an animal of the same species as my darling pet. Aside from duck, Third Brother and I shared an aversion to fatty meat, taking great pains to hide or discard any fat on our plates. I now looked with revulsion at my portion of duck meat with its underlying layer of soft yellow fat. Apparently Third Brother felt the same because I saw him extract his piece of duck when no one was looking and slip it into his trouser pocket.

I had eaten everything except my duck. Slowly, I lifted the duck with my chopsticks and let it drop to the table as if by accident. Father was complaining of the heat. I watched the beads of sweat glistening on his forehead and wondered why he didn’t remove his jacket and tie. Every night he and Niang came down to dinner dressed to the nines: he in a stiff white shirt, knotted black tie, long pants and matching jacket; she in a stylish dress with all her make‐up and not a hair out of place. Wouldn’t he be more comfortable in a tennis shirt and shorts and she in a loose house dress?

I was thinking of sticking the piece of duck to the bottom of the dining‐table when I saw Niang glancing at me suspiciously. Quickly, I popped the revolting morsel into my mouth and held it there without chewing or swallowing. Niang was instructing the maid to bring in a fan.

Muttering about having to go to the bathroom, I rushed out, spat my mouthful into the toilet and flushed it down.

When I returned, Niang was describing the dog‐obedience lesson she had received with Jackie from Hans Herzog that morning. Mr Herzog was a renowned German dog‐trainer. His lessons were highly selective because Jackie was being taught to obey only Father, Niang and Fourth Brother, who took turns attending Mr Herzog’s sessions with Jackie.