Christmas Tales of Alabama (10 page)

Read Christmas Tales of Alabama Online

Authors: Kelly Kazek

It was the week before Christmas 1938, and Hodges, thirty-five, a convicted rapist, was being released for a two-week Christmas furlough. He gave his word that he would turn himself back into authorities in January, which he did. Not everyone was as honest.

The practice was begun by Governor Bibb Graves in 1927 after inmates rioted over conditions. He would later tell the Associated Press, “The way to redeem an erring man is to show him a little kindness.” Graves also said the release allowed the men to help their wives and children financially.

The practice began not long after the end of the controversial practice of leasing convict labor for work in coal mines, farms and lumberyards. The convict lease system was begun in 1875, and by the 1880s, most of the state's prisoners served their time working in mines. The companies paid the state a fee per prisoner per month, and the state turned a profit. Rumblings had begun about the horrific conditions in which the prisoners, mostly African American, worked, but the 1911 explosion in the Banner Coal Mine that killed 123 black inmates started protests in earnest. It would take until 1928 for the system to finally come to an end.

The

New York Times

reported on June 30, 1928: “Strains of âSwing Low, Sweet Chariot,' and âAll My Troubles Are Over' wafted from shafts of coal mines here today as 800 negro convicts completed their last âtask' under the Alabama convict lease system.” On the heels of the demise of that system, Governor Graves's Christmas parole practice was a feel-good measure that was a dichotomy. It painted the prison system in a good light, but officials were forced to defend it each year in the press.

The 1939

LIFE

story touted the practice as a successâonly 63 inmates of 3,023 had not returned over the yearsâbut in another year, the tradition would end. Graves was governor from 1927 to 1931 and again from 1935 to 1939, with Benjamin Miller serving the term in between. Over the course of twelve years, fewer inmates were winning the privilege, and fewer of those were returning to prison in January.

In 1938, only 149 of 1,638 inmates at Kilby were released for Christmas. The perk was given only to the most well-behaved prisoners, and they left the prison with a promise to return on a designated day in January. In 1937, the Associated Press reported that only 16 of 554 inmates paroled for the two-week period did not return. The January 5, 1938 edition of the

Spartanburg Herald-Journal

in South Carolina ran the story, reporting:

Missing Christmas parolees became parole violators on Alabama prison records tonight, and authorities admitted at least 16 of 554 who won two-week vacation were still outâ48 hours after the reporting deadline. As parole violators they are subject to immediate arrest, and when brought back, as they usually are, they face prison punishment that could include a lashing and solitary confinement

.

After Christmas 1936, 15 of 454 prisoners did not return, leaving Governor Graves to defend the practice to the Associated Press: “Even among the 12 disciples, there was a Judas,” Governor Graves said, “and these are but sinnersâ¦I don't see why those who kept the faith should be penalized for that 3 percent.”

By 1935, several states were offering Christmas clemency, including Colorado, Florida, Maine, Massachusetts, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

In some states, even violent criminals were freed. The

Pittsburgh Post Gazette

reported on December 25, 1935, that seven convicted murderers were released for the holidaysâtwo in Massachusetts and five in Chicago.

In the fall of 1939, the Alabama legislature voted to create a board of pardons and paroles. One of the first acts of the three-member board was abolishing Christmas paroles. Instead, the board almost immediately permanently paroled 150 prisoners.

Graves would always consider the practice a success, as he told the Associated Press: “I believe a man who has sinned is entitled to a second chanceâ¦I believe it is better for these men to be free and in position to assist their wives and children than to keep them locked up in prisonâ¦I have faith in human nature.”

F

RED

,

THE

T

OWN

D

OG

It was two days before Christmas 2002 when Fred, beloved by his community, drew his last breath. Hundreds went into mourning. The Reverend John W. Cruse gave the eulogy, saying, in part, “Fred made our lives more enjoyable and gave us cause to laugh and find joy in his companyâ¦from him we learned many lessons, such as the quality of naturalness and the unembarrassed request for affection.”

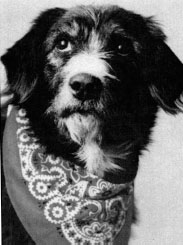

At his death, Fred was about thirteen years old. For the last nine of those years, he had been known as “Fred the Town Dog,” an Airedale mix that wandered into Rockford, Alabamaâpopulation 428âand stole the hearts of residents. When Fred's owner couldn't be located, several people, including Inez Warren, tried to give the dirt-caked mutt a permanent home. Fred was determined to be a free spirit. Caring townspeople took him to be groomed and for medical treatment. The veterinarian said Fred had been shot at some point during his wanderings, but he seemed none the worse for wear.

The dog had a “home base” at Ken Shaw's convenience store, but he wandered the streets each day, greeting friends and welcoming visitors with a wag and welcoming visitors. Of course, Fred wasn't averse to taking a handout and often ate dinner “out.” He sometimes even wandered inside and slept in people's homes. Fred would nap wherever the mood struck him, whether on the cool concrete at the service station or in the middle of the road, where patient residents would get out of their cars and move him to safety.

Fred, the Town Dog of Rockford, died on December 23, 2002.

Courtesy of Kenneth Shaw

.

Though he had few talents beyond napping, licking his nether regions and wagging a friendly tail, Fred soon would become a celebrity. The signs at the town limits were changed to say “Rockford, Alabama, Home of Fred the Town Dog.” Shaw sold Fred the Town Dog souvenirs, such as T-shirts, coffee mugs and caps, and proceeds paid for Fred's food and medical expenses. The dog had its own account at the local bank.

Fred also began “writing” a columnâwith the help of a few human friendsâfor the local weekly newspaper, the Coosa County News.

An Associated Press reporter wrote about the tiny town with the dog mascot, and the story was published nationwide. Then the TV network Animal Planet featured Fred on one of its shows. People came from other states to visit Fred, and many brought their dogs to meet the famous mutt. Although a few disgruntled residents did not want their hometown to become famous because of a stray dog, the majority of people were amused by Fred's antics and musings in the column.

Fred also gave back to the community. He appeared at fundraisers for the American Cancer Society, and he loved helping the Easter Bunny during the town Easter egg hunt. Christmas, though, was his favorite time of year. In one undated Christmas column, Fred “told” residents of the upcoming parade and described how Ken Shaw and friends decorated his float. “With that Wal-Mart special light sale on we found some neat thangs to put on it so's everyone can judge my float the best.”

For several years, the Rockford Christmas parade featured a float carrying Fred, usually bedecked in holiday attire, including a red cape with holly and often a pair of plush reindeer antlers. A few years before he died, Fred was struck by a car while crossing the street. No one thought he would survive. But Fred, who had taken a bullet and lived by his wits all his life, wasn't ready to go. Dr. John Christianson at Birmingham's Montclair Animal Hospital was able to set his broken leg, and his internal injuries miraculously healed.

Then, on Halloween 2002, Fred was the victim of a cruel twist of fate. He was bitten by what doctors believe was a spider or snake. For weeks, his valiant veterinarians fought to remove the poisons from his aging body to no avail. A few weeks before Christmas, Ken mailed three hundred Christmas cards featuring a photo of Fred to people across the country who had visited or written about the dog.

A column by Fred published on December 20 gave a brave report and thanked people for their concern: “For those of y'all who don't know I have decided to take a two-week hiatus up at Doc Christiansen's place in Birmingham for a little R&R while I get pampered with lots of attention, lots of biscuits and gravy, and lots of Christmas and New Year Get Well cards.”

Before Ken had to agonize over whether to euthanize the beloved dog, Fred died peacefully in his sleep. While that was a blessing, his death created a mournful Christmas for his Rockford family. Those who had known him wept.

Fred would be buried in a specially made casket. Local schoolchildren wrote notes of farewell in colorful crayon.

Fred's body was taken to a spot behind the historic Old Rock Jail near downtown and laid to rest with Ken Shaw, Judge Robert Teel Jr., Police Officer Jimmy Hale, local artist Charlie Simpson and another caregiver, Katurah Stewart, in attendance. A father and his children who had seen Fred on Animal Planet made a rest stop in town, heard about the service and decided to pay their respects.

The Reverend Cruse read from Psalms and then the eulogy he'd written himself. With proceeds from the sale of “Fred” souvenirs, the dog's human friends erected a monument featuring a photo of Fred wearing his familiar red bandana. “FRED” is etched in large letters and beneath them, “The Town Dog, Rockford, AL, Dec. 23, 2002, Rockford's Beloved Companion.”

In 2004, Fred was inducted into the Alabama Animal Hall of Fame. He was nominated by Dr. Christian. The site at

alvma.com

states, “Fred was voted into the Hall of Fame because of his unusual dedication to this town and the respect citizens of the town had for him.”

As the Reverend Cruse said at Fred's funeral,

To those who have never had a pet this prayer will sound strange, but to You, Lord of All Life and Creator of all Creatures, it will be understandable. Our heart is heavy as we face the loss in death of our beloved Fred the Town Dogâ¦He wandered up and into the lives of Rockford and all those who came through and stopped to pet him and be a part of his worldâ¦May Fred sleep in an eternal slumber in Godly care

.

Today, the signs naming Rockford “Home of Fred the Town Dog” have been removed, but people haven't forgotten the lovable mutt that stole their hearts. They may pass his grave site, the elementary school or the courthouse steps and smile at the thought of Fred, the dog that, with a wag of his tail and tongue, reminded them of the immeasurable gift of unconditional love.

T

HE

G

IRL

W

HO

S

AW

A

NOTHER

S

UNRISE

The scene at Piedmont Hospital was like a wake. Friends and family of little Donna McDowell came and went from her hospital room, saying their goodbyes. It was December 21, 1959, and eleven-year-old Donna was not expected to celebrate another Christmas or even see another sunrise. She was not in painânot yet. The explosion and fire earlier in the day that had burned 87 percent of her body had damaged her nerve endings. Doctors cut the clothing from her body and made her comfortable, then relayed the news that there was no way anyone could survive such severe injuries. No one ever had.

Donna would prove the doctors wrong. Miraculously, she was still alive on December 22. At the time, though, Donna could not know the long and painful recovery that lay ahead.

What had begun as a fun afternoon with her beloved father had turned into a family's worst nightmare. On the afternoon of December 21, Donna and her father, John Charles “J.C.” McDowell, the prominent owner of several local textile mills and a friend of Governor John Patterson, went to a fireworks stand to buy sparklers to celebrate Christmas Day. J.C., a dropout and World War II veteran who drove a bread truck, had talked his way into a job running a local mill, gone back for his diploma and then his bachelor's and master's degrees and worked hard until he became the owner of five mills. He married Mary Upton, and they had two children, Donna and Larry.

Donna adored her father.

Father and daughter arrived at a fireworks stand owned by the husband of a worker in one of J.C.'s mills. It was housed in an abandoned cotton mill warehouse. After entering, little Donna wandered to the bathroom in the back of the building. Suddenly, she heard her father cry out; a massive explosion followed. Windows shattered, firecrackers popped and boomed, like a series of bombs. Flames licked at the walls of the old building. There were no regulations about smoking around explosives, and a cigarette carelessly tossed by the stand's owner had ignited an inferno.

Though her father and the owner were near the entrance and were able to exit safely, Donna was trapped. When she heard her father calling her name, the frightened girl walked toward him, not realizing there was any other way to get to him than walking through fire. She made her way through the blaze, feeling as if she were wrapped in God's arms. As the building became engulfed, an off-duty state trooper saw the fire and stopped to help. A local resident, Johnny Floyd, also arrived at the parking lot. When the men saw the burning child exit the building, Johnny threw his coat over the flames, extinguishing them. The trooper, Captain Southerland, carried Donna to his car, where her father knelt in the back seat and, for the entire ride to Piedmont Hospital, held Donna under her arms so she would not touch the seat. If she had, her blackened skin would have been ripped away.