Christmas Tales of Alabama (6 page)

Read Christmas Tales of Alabama Online

Authors: Kelly Kazek

Del recalled that in the early days as bookkeeper at Loveman's, female employees and “sales ladies” had to uphold strict standards. “Back then we could wear black, blue, navy or brown, or a print no larger than a dime,” she told the

Birmingham News

in 1980, adding that women were sent home for wearing “loud prints.” Her love of Christmas and children led the woman who would remain childless to don her Twinkles costume each Christmas, complete with a jingle-belled hat and booties. It was while in character as Twinkles that she became friends with Cousin Cliff.

As a teen, Clifton Holman began performing magic tricks and comedy acts around Birmingham in the late 1940s. When he was twenty, he was working in Loveman's credit department when supervisors asked him to be the voice of Mr. Bingle, the snowman marionette character of its parent company, City Stores of New York. Loveman's presented a Christmas show from the store that aired on Birmingham's Channel 13.

For several years, the show would air from Thanksgiving through Christmas and promote Loveman's. Cousin Cliff would repeat the rhyme that began: “My name is Mr. Bingle, I work with Kris Kringle⦔

After returning to Birmingham from fighting in the Korean War, Holman would go on to have a successful television career with his

Cousin Cliff's Clubhouse

children's show on Channel 13. His career spanned five decades. Flagg recalls seeing Holman's show at Loveman's and on television. “He was our local Howdy Doody,” she said.

It was her fond memories of Twinkles, a woman who was part of the fabric of her life but whom she never met, that helped Flagg create the character of Hazel, an unstoppable force who never had a bad day. Twinkles has said that no one at Loveman's or in the community ever “let on” that she was smaller than most people.

The tiny, ninety-year-old woman, whom caregivers and nurses call “Twinkles” to this day, told a reporter with the

Birmingham News

in 1995, “My parents taught me there was a big world out there, but it would be up to me to go out and make something of it.”

P

EARSONS

M

ADE

S

URE

O

THERS

H

AD

C

HRISTMAS

Christmas of 1930 was a sad one in Autaugaville.

It had been just over a year since the stock market crash officially started the Great Depression, but it began months before for farmers in this small central Alabama town, where the boll weevil was wreaking havoc on crops. The hardships were evident to Edward and Ercille Pearson, who owned a local general store. Each day, the Pearsons saw the wistful eyes of children as they roamed the shelves of dolls and train sets and jars of penny candy as their parents bought stocks of flour and bacon.

On Christmas Eve, Edward Pearson looked at the still-filled shelves of his store and knew that this year few toys would make their way under Christmas trees or into stockings in Autaugaville. This Christmas would be just another day for most local children. The supply of juicy oranges, ripe apples and tasty candies in Edward's store would likely go to waste. Soon he formulated a plan: he would give the items to children for Christmas.

On December 26, Edward and Ercille, with two-year-old Frances in tow, placed the unsold items into their Chevrolet sedan and drove through town, distributing them wherever they found children.

That first Christmas of the Depression turned happy in Autaugaville.

Edward and Ercille had been married eight years by then and had made a decent living with the store, at which they sold everything from groceries to plows to furniture. The store was, for a general mercantile of the day, considered fancy. Its floors were concrete rather than plank, and an Artesian well in the center of the store served as a drinking fountain.

Edward was ahead of his time in another way: he served everyone in town, black or white, and all were welcome to drink from the same fountain.

Edwardâborn on October 22, 1896, to Albert Augustus and Mary Catherine Hick Pearson in Montgomeryâsaw no reason not to share his good fortune with his neighbors, who consisted largely of sharecroppers. For each year after that first giveaway, Edward would make the same promise: whatever was left over in the store the day after Christmas would be distributed to any child who came.

As the tradition grew, the distribution changed. The Pearsons would erect signs around town and tell local folks where he would be on December 26. All children were welcome.

Ercille gave birth to little James in 1931 and Rufus in 1933, and before long, the three children were accompanying their parents on the annual Christmas giveaway. Edward eventually began giving gifts to children outside Autaugaville. But he couldn't afford to give all the merchandise from his store, so he would spend weeks before Christmas driving around the state, picking up donations so that kids would have fruit, nuts, candy and some type of toy, perhaps a small doll, a wooden truck or a stick gun, for Christmas.

Edward began to ask friends to play Santa Claus, and he would make stops at several distribution points throughout the day. At some stops, he would find five or ten children waiting for toys, fruits and candy. At others, as many as thirty children would gather around.

Although there were times when Ercille wanted her family home for Christmas, Edward would not disappoint the children. He continued the tradition until 1961. Edward died on February 21, 1962.

That Christmas, Rufus and James, who had always told their father that they would carry on his good works, organized Christmas for Autaguaville's families in need. They realized, though, that it wasn't the same.

Not only did they miss their father, who was at the heart of the effort, but also times had changed. People were more affluent, and fewer families came for free gifts. It would be the last Christmas for the Pearson giveaway.

Ercille, who was born in 1904, lived two more decades before her death in September 1982. She was buried beside her husband, Autaugaville's Santa Claus, in Rocky Hill Cemetery. Many of the children who wouldn't have had a toy at Christmas without the Pearsons have not forgotten.

Rufus and James said people approach them often to tell them what their father meant to them. “Nobody had much then, and a lot of them, that's all they got,” Rufus said.

G

LENN

M

ILLER

'

S

L

EGACY

C

ONTINUES IN

A

LABAMA

On Christmas Day 1944, the world received shocking news: Glenn Miller, America's best-known big band leader, was missing.

The

New York Times

reported on December 25: “Major Glenn Miller, director of the U.S. Air Force Band, is missing on a flight from England to Paris. No trace of the plane has been found.”

Ten days earlier, Miller had been aboard a single-engine UC-64 Norseman that was flying from Bedfordshire to Paris to make arrangements for his Army Air Force Band to perform a Christmas Day concert when the plane disappeared over the English Channel. The body of the iconic bandleader was never found. Sixty-seven years later, he is still listed as missing in action.

He left behind his wife, Helen; son Stevie, born in 1942; and daughter Jonnie, who was adopted as an infant a few weeks before the plane went down and whom Miller never saw. Helen spent the rest of her life awaiting her beloved husband's return, refusing to believe he had died. Many members of his Army Air Force Band were quoted in newspapers over the next two years repeating the sentiment that they, too, felt their leader would one day return.

Among those who mourned the loss were Miller's fellow soldiers at the Army Air Force Southeast Training Center at Maxwell Field, now Maxwell Air Force Base, in Montgomery, Alabama. After volunteering for and being turned down by the navy, the then thirty-eight-year-old Miller entered the army in 1942, later to be transferred to the U.S. Army Air Force. His assignment was to form a band and entertain troops. He was determined to play for those on the front lines.

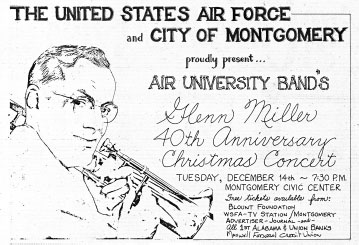

Glenn Miller played a Christmas concert when he was stationed at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery in 1942. He disappeared over the English Channel. This advertisement for the first commemorative concert appeared in the air force base newsletter in 1982.

Courtesy of Dr. Robert Kane

.

His training began at Maxwell in November 1942 as an assistant special services officer. Before long, Miller had formed a fifteen-piece band called the Rhythmaires. In addition to leading, Miller also played trombone. The band performed both at civilian clubs and for troops.

Accustomed to playing for a crowd, Miller set out to hold a holiday concert for the men and women on base. The event was planned for Christmas Eve 1942 in a hangar on the base. Featuring Glenn Miller standards such as “In the Mood” and “Pennsylvania 6-5000,” the concert was a hit. It also was broadcast live on radio stations in Birmingham and Montgomery.

For several more months, Miller trained at the base. He then spent some time trying to modernize military marches, which met with some resistance. He combined blues and jazz with traditional marches to create the arrangement called “St. Louis Blues March.”

In the summer of 1944, Miller left for England to perform with his much larger Army Air Force Band, which gave eight hundred performances through early December. After the D-Day invasion in 1944, Miller was ordered to France. He flew ahead of his band to make arrangements and was never seen again. No part of the plane or its passengers has been discovered.

Although some historians believe bad weather led to the crash, some documents suggest that the Norseman may have been struck by bombs jettisoned by Allied bombers returning from an aborted mission. A memorial to Miller was erected in Arlington Cemetery in 1992.

Glenn Miller was born on March 1, 1904, in Clarinda, Iowa, to Lewis Elmer Miller and Mattie Lou Cavender Miller. He got his first trombone in 1916 before his family moved to Colorado, where he attended college. He became a success using the philosophy that a band should have “personality.” In the 1930s, Miller, then living with Helen in New York, also appeared in three feature films.

When

The Glenn Miller Story

was released in 1954, Miller was portrayed by Jimmy Stewart and Helen Miller was portrayed by June Allyson. Helen died in 1966 at age sixty-four.

In 1982, Major Earl Turner, leader of the Maxwell Air University Band, went to Lieutenant General Charles Cleveland, commander of Air University, and suggested giving a concert on the fortieth anniversary of Miller's Alabama concert. Turner wanted band members to wear “pinks and greens,” the nickname for the Army Air Force uniforms worn during World War II, and perform Glenn Miller's biggest hits, along with some jazzed-up versions of traditional Christmas tunes.

Cleveland thought it was a great idea, and soon the city of Montgomery was on board. The concert was held in the civic center on December 14, and eight thousand people attended. Every Christmas since then, the band at Maxwell has been hosting the Glenn Miller Commemorative Christmas Concert. The event pays tribute to a man whose patriotism drove him to serve his country. When the Army Air Force Band returned home after playing its last World War II concert in 1945 without its famed leader, comedian Eddie Cantor gave an emotional speech:

Glenn Miller was a very wonderful manâ¦Glenn could have stayed here. He could have stayed and made himself a lot of money. And then if he wanted to, he could have retired, an independently wealthy man. But he chose not to. He was an extremely patriotic man, and he felt an intense obligation to serve his countryâ¦He took himself and his orchestra overseas, to where he felt he could do the most good for our fighting menâ¦He made the supreme sacrifice for his country. But he will never be forgotten, for always we will have the sound of the great music he created

.

P

RANCER

,

THE

S

OUTHERN

R

EINDEER

Four thousand miles south of the North Pole, Alabama is an unlikely place to find reindeer. It is an even more unlikely spot for a reindeer to become a movie star. In 1987, a reindeer named Boo, who was raised in Huntsville from the age of five, went to a casting call and was chosen for the titular role in the film

Prancer

, the story of a little girl and an injured reindeer, which would become one of the holiday favorites that year.