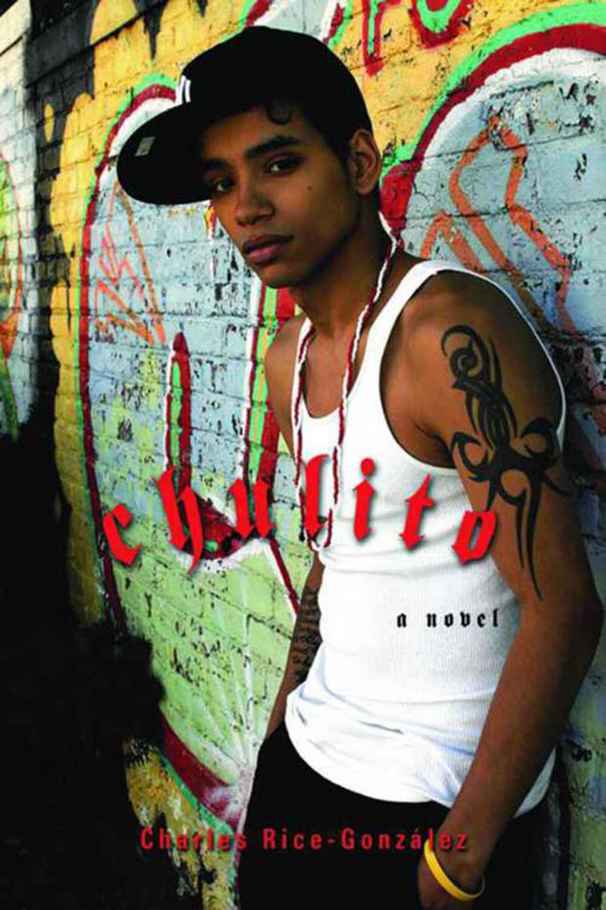

Chulito

Authors: Charles Rice-Gonzalez

Copyright © 2011 by Charles Rice-González

Magnus Books

An Imprint of Riverdale Avenue Books

5676 Riverside Drive, Suite 101

Riverdale, NY 10471

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Magnus Books edition 2011

Cover by: Scott Idleman/Blink Design

ISBN: 978-1-936833-98-6

www.riverdaleavebooks.com

Dedicated to

The one and only Freda Rosen, who said,

“Charles, if anyone can write this particular story and get it published, it’s you.”

And to my Troika of Support

Cassandra

Arthur Aviles

My mom, Maria Narvaez

Chulito awoke with a hard-on as usual. He looked down his smooth, brown chest past the black strands sprouting around his navel to see the head of his dick poking up at him through his bed sheet. He greeted it with a firm gentle squeeze. “Hola, papito.”

The old window shade in his tiny room cast a Creamsicle glow from the sun rays that shot off a big metallic sign from one of the many auto glass shops that lined the street across from his building.

The sounds of trucks revving and barreling along Garrison Avenue mixed with the cries of “auto glass! auto glass! auto glass!” from the guys who competed with each other to lure cars with broken windshields, cracked mirrors or busted headlights into their respective shops.

Chulito stood naked in front of the full length mirror on the back of his door. That spring, with just some push-ups and sit-ups, smooth hard muscles came out of nowhere and he looked like a Latino, hip hop version of Michaelangelo’s David. He crossed his arms over his chest, fingers underneath each armpit and thumbs pointing up to the ceiling. He shifted his weight onto his right hip, tilted his head, tucked his chin into his neck, and contorted his pretty boy face into a mean gangsta snarl.

He then popped a CD into his system and mouthed out the words along with Big Pun. When the percussion popped into the song, he bopped his head and challenged his own image in the mirror.

As Chulito slipped into the bathroom across the hall from his room, his nostrils filled with the comforting smell of freshly brewed Café Bustelo. He heard his mother, Carmen, talking in the kitchen with Maria from upstairs about her son Carlos, who was coming home from his first year at college. All week he’d heard Maria’s slippers make sounds like sandpaper scratching on the bare wood floor as she prepared Carlos’ room, which was right above his.

Chulito was excited, too. Carlos used to be his boy. They were real tight from the day Carlos and Maria moved into the building. Carlos was five, almost a year older than Chulito, and would come home from kindergarten and teach Chulito the songs he’d learned. Growing up, they played together all the time—snowball fights, trick-or-treating on Halloween, going to Joe’s for ices, or sneaking into El Coche Strip Club and laughing real hard when they got chased out by the old Irish owner.

But that was before all the shit came down.

It started when they went to different schools. Chulito went to Stevenson High School, the local school that everyone in Hunts Point attended, but Carlos got accepted into the Bronx High School of Science in the North Bronx, a school for the gifted and intelligent. Maria threw him a party when he got accepted and took a second job to buy him a new laptop. Then Carlos started dressing differently, like one of those white boys in the J. Crew catalogs. Chulito didn’t care, at first; he thought Carlos looked cool and sophisticated. They still spent time together. Carlos helped him with homework and they rode the number six train to Parkchester to see movies on the weekends. They were always together. Then people in the neighborhood started calling Carlos a pato.

“We should kick his faggot ass to show him a lesson,” said Looney Tunes, one of the fellas who hung out on the corner and lived in Chulito’s building. Looney Tunes earned his name because as a kid he ran home from school to watch cartoons. He even watched them on videotape, sang the songs and imitated the noises and sound effects. He grew out of it, but the name stuck.

Chulito stared Looney Tunes down. “Yo, Carlos is my boy and he from the ’hood, so cut that shit.”

“Protecting your boyfriend?” Looney Tunes teased. Chulito responded with a punch that knocked Looney Tunes on his ass and required three stitches on the inside of his mouth. So everybody left Carlos alone—including Chulito. It was just what he had to do to be correct with the fellas. Carlos tried to stay connected, but he was placed in pato exile—no one looked at him or talked to him.

Chulito hated treating Carlos as if he were invisible whenever he ran into him in the Bella Vista Pizza Shop or saw him walking up the block. Chulito got heated when the fellas made “faggot this” and “faggot that” comments when Carlos passed the corner, but he kept it in check. He’d successfully avoided Carlos until one day, while coming out of the bodega, he collided with him. The fellas were on the corner right outside the door watching. Carlos looked surprised at first, then the corners of his mouth curled into a smile. Chulito wanted to say “sorry” or “excuse me” but instead said, “Watch where you’re fucking walking.” The fellas laughed. The hurt in Carlos’ eyes haunted him for the next week.

He finally went to meet Carlos at his school, which was safely a world away from Hunts Point. He was worried that things with the fellas could get out of hand. He wanted to protect Carlos, so he told him to get correct and stop fagging out.

Carlos looked down at his fitted yellow Polo shirt, straight-legged jeans and red Adidas sneakers with the white stripes and held out his slim arms. “There’s nothing wrong with me, Chulito. There’s nothing wrong with not wearing drooping pants and Timberlands all the time. Look around, people dress all different kinds of ways. And I’m still the same Carlos. It’s the neighborhood that’s fucked up.”

Chulito checked out Carlos’ friends waiting nearby with their mohawks, dread locks and fuschia dyed hair. He looked back at Carlos. He wanted to confess that he missed him, he missed the movies and the walks near the empty industrial streets of the Hunts Point Food Market, the laughs, and the long telephone conversations where Carlos told him the storylines of the books he was reading, but instead said, “I’m just trying to look out, ‘cause the fellas be getting worked up.” Chulito shoved his hands deeper into his pockets and looked at the ground.

“Thanks for looking out for me, Chulito. I know you’re not like the rest of those assholes.” Carlos touched his shoulder. Chulito’s heart quickened.

On Carlos’ graduation night, Chulito was hanging out on the corner with the fellas when Looney Tunes said, “Oh shit! Look, Carlos is holding hands with a dude.” One of the auto glass guys sarcastically called out, “Oh, qué cute,” which opened a flood gate of catcalls. When Chulito saw Carlos holding hands with his date a rush of anger swept over him. Is he messing with that dude? It was the same guy with the long blond dreads from his visit to Carlos’ school. As the pair crossed the street, the auto glass guys and some of the fellas on the corner blew kisses at them. Looney Tunes walked around with a limp wrist and called out Carlos’ name in falsetto.

“That’s right.” Papo, one of the other fellas on the corner shouted, “You better walk fast before we fuck ya ass up, Carlos.”

Carlos looked over his shoulder at Chulito, then kissed his date on the cheek. Chulito had trouble breathing and the neighborhood became a blur.

“Who the fuck does he think he is doing that shit over here?” Papo asked. “This ain’t the Village.” He picked up a bottle and hurled it. Carlos and the blond guy jumped as it shattered a few feet behind them. The auto glass guys and the fellas laughed. “You see that, Chulito? You stick your neck out for him and this is what he does. He’s a fucking faggot. A dirty pato.” Then Papo handed Chulito a bottle and gestured with his head to throw it. “Throw it!” one of the auto glass guys yelled. Then someone else said, “Throw it, Chulito.” From all around Chulito the “throw its” shot like arrows. Carlos turned to see what was happening and noticed Chulito holding the bottle. They made eye contact. “Throw it, Chulito!” Papo urged. Chulito wished Carlos had done this when he wasn’t around, then ran three steps forward and hurled the bottle into the lavender sky. As the bottle left his hands he wanted to fly with it and stop it mid-air. The bottle hit the blond guy on the shoulder, bounced off and crashed on the ground. The hecklers erupted into laughter, hissed and doubled over. “Bull’s eye.” Papo winked at Chulito.

The guy turned to confront the crowd. “What? Looks like that faggot wants a showdown. Let’s get ‘im fellas.” Papo charged into the street. Chulito followed. He wanted to hurt that guy. He wanted to show him who’s top dawg. Carlos tugged his date’s arm and the two ran down Hunts Point Avenue. Papo laughed and stopped, along with the other fellas, in the middle of the street. “You betta run, faggots.”

Chulito continued to sprint after Carlos and his date as they crossed under the Bruckner Expressway and dashed down the steps to the train station. The honking from the oncoming traffic under the highway made him stop. He stood on the median gasping and coughing. His lungs burned and his body tingled, then he pressed his eyes to keep back the tears. He thought, How could Carlos disrespect the neighborhood like that? But he felt personally betrayed.

Chulito didn’t talk to him again, and later that summer Carlos left for school on Long Island.

A year later and about a month before Carlos came home from his first year at Adelphi, his mother got sick. She thought she was having a heart attack, but it turned out to be some bad pork in the mofongo she ate from the 97 Café. That night they learned how popular that mofongo was when three people in their building also got sick and ended up in the emergency room. Chulito’s mother took Maria to the hospital and asked Chulito to call Carlos because they hadn’t reached him.

Chulito sat in his room and stared at his phone. Carlos’ number was still his first number on his speed dial. He pressed it, but before the phone finished dialing, he closed it. Would he just keep it business and say “Your mom got sick but she O.K.?” What else would he say? He felt like Carlos had dissed him and owed him an apology. He pressed number one again. When Carlos came on, Chulito’s thoughts became a tangle of apologies and questions.

“Hello?” Carlos repeated. “Chulito?”

Chulito must have still been in Carlos’ phone. Chulito closed his eyes and took a deep breath. “My moms asked me to call you, ‘cause your moms got sick from some food, but she O.K.” Chulito slipped off his loosely tied Timberland boots, laid back on his bed and looked up at the ceiling that had the original light fixture which looked like a lotus flower covered in quarter inch of thick white paint. He pretended that Carlos was right beyond that light fixture, in his room, resting on his bed.

“I saw there was a missed call from my mom and called her back but there was no answer. Are you sure she’s O.K.?”

“Yeah, she didn’t want to worry you ‘cause it ain’t serious. They should be on their way back from the hospital.”

Chulito liked hearing Carlos’ voice. He wanted to say so, but held back. He could still see Carlos holding that blond guy’s hand, kissing his cheek.

“Well, thanks for calling.” Carlos sounded distant and cold.

Neither spoke.

Then, as if someone had hijacked Chulito’s brain, he started speaking. “Yo, sorry I haven’t called you.” His throat dried up.

“You’ve got something to say?”

“Nah.”

“Well, why were you going to call me?”