City of Scoundrels: The 12 Days of Disaster That Gave Birth to Modern Chicago (25 page)

Read City of Scoundrels: The 12 Days of Disaster That Gave Birth to Modern Chicago Online

Authors: Gary Krist

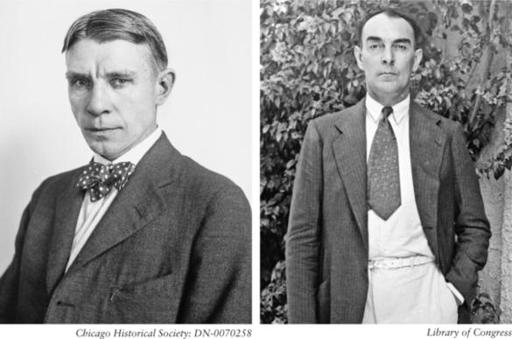

Caught up in the summer crisis were numerous Chicagoans of greater or lesser fame. Carl Sandburg (left) reported on the riot for the

Chicago Daily News.

Ring Lardner (right) was a columnist for the

Tribune.

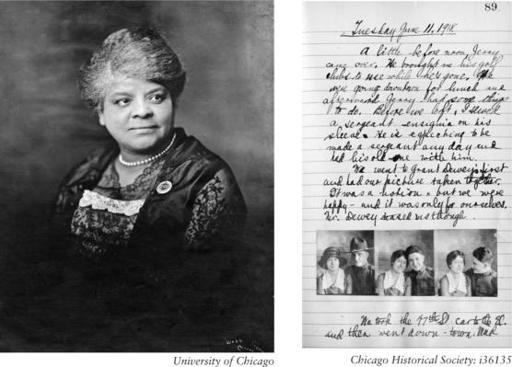

Activist Ida Wells-Barnett (left) worked to help the victims of the rioting in the city’s Black Belt. And young Emily Frankenstein (right), seen here with her fiancé, Jerry Lapiner, recorded the unfolding events in her diary.

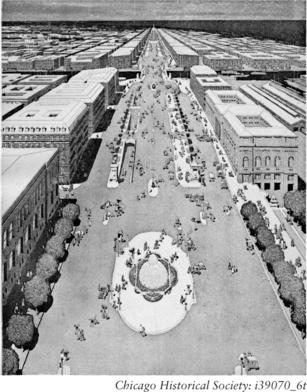

The effect of the 1919 crisis was to leave Chicago a chastened but, in many ways, a stronger city. While dreams of implementing architect Daniel Burnham’s wildly ambitious Chicago Plan were never fully realized, the city did see remarkable urban improvements in the 1920s.

Today, showpieces such as the Magnificent Mile of Michigan Avenue make Chicago perhaps the most architecturally distinguished city in the Americas—in large part thanks to the leadership, however corrupt, of Big Bill Thompson.

I

WAS SITTING

in the window [at home] at 10 minutes after 12 on Tuesday,” Fitzgerald began, “when I saw Janet coming towards the building.”

Howe listened in silence, alone with Fitzgerald in the hot, cramped jail cell. Later, the prisoner’s words would be recorded by an official police stenographer before a roomful of men. But Howe must have known that any sudden call for witnesses might cause the prisoner to balk yet again, and so he let him speak. For now, the lieutenant just needed to hear what had happened.

“When she came up the stairs to the landing,” Fitzgerald continued. “[I was waiting] at my doorway. I said to her, ‘Dolly, would you like some candy?’ ”

The child had paused on the landing then. Apparently, she was tempted. As hackneyed and transparent as the offer might sound to modern ears, it must have seemed enticing to Janet. But the girl would have remembered her parents’ warning not to go near this man.

Fitzgerald, however, didn’t give her time to refuse. “I picked her up in my arms,” he said, “and carried her into my apartment.”

He wasn’t prepared for what came next: “She started to scream. [And] before I knew it or realized what I was doing, I grabbed her by the throat and choked her to death.”

It was over very quickly. When he understood what he had done, Fitzgerald, still in his bathrobe, put the child down on his bed and quickly dressed. Then he picked her up again and carried her to the

door of his apartment. After checking to make sure no other tenant was in the stairwell, he took Janet’s body down the stairs to the basement—“where I buried it under a pile of coal.”

1

This was all Howe needed to hear. Any uncertainty was gone now. The child was dead, and he had the man who did it. He notified the other interrogators, sent word to Deputy Chief Alcock, and brought the prisoner upstairs to dictate his official sworn confession. The statement was written out in longhand and then signed by Fitzgerald and witnessed by Howe, Detective Sergeants Quinn and Powers,

Tribune

city editor Perley H. Boone, and W. C. Howey, managing editor of the

Herald and Examiner

.

At 9:15, Deputy Chief Alcock arrived at the station. He examined the written confession and then he, Lieutenant Howe, and a guard of detectives and reporters took Fitzgerald over to the duplex building on East Superior Street. In the basement, sanitation workers and police were still sifting through the enormous pile of coal stored there. Fitzgerald walked over to one corner of the basement where a rusty iron chimney stuck out of the coal pile near the wall. “She’s over there,” he said, pointing to a narrow, coal-filled space between the chimney and the wall. Somehow, over days of searching, the workers hadn’t looked in this space, perhaps because they regarded it as too small to contain a body.

“Do you want to lift her out?” Detective Sergeant Powers asked him.

Fitzgerald acquiesced, but when he bent over, the pale, exhausted prisoner found he couldn’t do it. Two of the sanitation workers came up behind him. “The head is here,” he said, showing them where to dig. “And the feet are over there.”

The two men started shoveling away the coal, but Deputy Chief Alcock told them to use their hands. Understanding, they threw aside their shovels and began gently pulling away the dusty black lumps. In a few minutes, they had uncovered a small figure wrapped in white cloth. It was wedged so tightly into the narrow space, however,

that they finally had to use a two-by-four to pry the chimney away from the wall, exposing the small, blackened corpse of Janet Wilkinson.

“I can’t stand it,” Fitzgerald said, turning away.

They lifted the body from the coal pile and placed it on a stretcher they had brought over from the police station. Then they carried it up the stairs and out to the street, where a police ambulance was waiting to take it away.

2

An angry crowd was already gathering around the entrance to the building. The newspaper reporters assigned to the case—who had been given a level of access to the investigation unimaginable today—had sent word of the confession to their city desks the moment it was made, and the

Tribune

had managed to put an extra on the streets by 9:15. Now, at 10:05, most of Fitzgerald’s neighbors had already heard about his confession, and they were apparently ready to take action. When Fitzgerald was brought to the front vestibule, the crowd grew restive. “Lynch him!” a few men shouted. “String him up!”

3

Fitzgerald recoiled and cowered in the doorway. It seemed possible that members of the crowd might indeed take the law into their own hands. Because of some confusion in arrangements, no police vehicle was waiting to take Fitzgerald back to the police station. “The crowd seemed to sense this fact,” one reporter from the

Herald and Examiner

later wrote, describing the scene. “It surged toward the building’s entrance.… A dozen uniformed policemen appeared powerless to stem the tide of enraged humanity.”

Fortunately, a number of plainclothes police arrived at that moment. “They elbowed their way through the crowd, knocking men, women, and even children right and left. With the reinforced guard now before the doorway, clubs and revolvers brandished menacingly, the crowd withdrew to the street.”

One policeman had commandeered a taxicab and brought it around to the duplex apartment. When it got to within ten feet of the

curb, Fitzgerald, surrounded by thirty policeman and detectives, was led from the entrance of the building.

“The howls of the multitude burst forth anew as the slayer came down the two steps from the front doorway to the sidewalk,” the paper reported. “Fitzgerald made no attempt to conceal his fear. His body shook visibly. His eyes were shut tight, as though he feared being struck down by missiles. He held a handkerchief tightly against his mouth and nose.”

What followed was a near riot. Fitzgerald was pushed into the back of the cab, but then the crowd swarmed the vehicle. Some reached in through the open windows on the opposite side to grab at the prisoner, who was now sprawled across the backseat. Detectives climbed over him and tried to beat away the arms and fists. One of the detectives barked an order to drive away. The cabbie sounded the horn. The crowd in front scattered as the taxi shot forward. “Amid parting hoots, shouts of dismay, and shrieks of women and children, Fitzgerald was borne away back to his cell.”

4

Another mob was waiting at the Chicago Avenue station when they arrived, but Fitzgerald’s police guard whisked him into the building before any spontaneous outbreak of violence could develop. Even so, Captain Mueller called for a hundred reserves from the city’s corps of traffic policemen. Some members of the mob were carrying “ill-concealed weapons,” so Mueller had police cordon off the area around the station. When the time came for Fitzgerald to make his official statement to the state’s attorney, he was spirited through a rear entrance and rushed in a waiting automobile to the Criminal Court Building. There, Assistant State’s Attorney M. F. Sullivan questioned him at length. Little new information emerged in this interrogation, though a few inconsistencies in the evidence were cleared up. Fitzgerald was described as “cool” and “a picture of control” throughout the process, though he was apparently more nervous than he let on. “Don’t let them hang me, will you, Mr. Howe?” he asked nervously

at the end of the interrogation. “Have them send me to some insane asylum?” The lieutenant didn’t answer.

But State’s Attorney Hoyne had other plans for Fitzgerald. He promptly turned over principal responsibility for the case to prosecutor James O’Brien—a man known around the Criminal Court Building as “Ropes” O’Brien, for his enthusiastic (and usually successful) pursuit of the death penalty in homicide cases. Hoyne promised that once Coroner Hoffman had completed his inquest in the case, expected to happen tomorrow, the pace of justice would be swift.

5