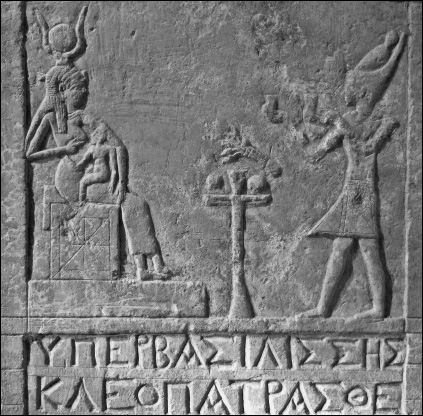

Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (13 page)

Read Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Egypt, #Biography & Autobiography, #Presidents & Heads of State

From this regrettably vague description we may develop a tentative plan of Ptolemaic Alexandria. ‘The Palaces’ (Bruchion), effectively an extensive elite town within the city, occupied the north-east sector, and included the now sunken peninsula of Lochias and island of Antirrhodos. Here were the spacious villas of the Greek upper classes, interspersed by temples and public gardens, and here too were the ‘Inner Palaces’, an even more exclusive area incorporating the Museion (or Museum: a research centre inspired by Aristotle’s Athenian Lyceum and dedicated to the nine Muses), the Soma, and the private residences and harbour of the kings. If Strabo is correct in his assertion that each Ptolemy built a new palace, creating a larger and more luxurious residence than those of his predecessors, this area must have been a warren of under-used royal buildings, colonnades and gardens. Alexandria suffered a devastating series of earthquakes in

AD

365, 447 and 535. At roughly the same time – no one is quite sure when it occurred – subsidence estimated at between thirteen and twenty-three feet removed the ancient coastline and submerged much of the ancient city. Today all the palaces and Ptolemaic royal tombs, Cleopatra’s included, lie under the waters of the harbour.

Strabo’s description of Alexandria outside the Palaces is even less precise, but we can deduce that the public facilities – the gymnasium, law courts and agora or marketplace – lay in the centre of the city, while the main theatre lay between the agora and the Palaces, with the hippodrome just outside the city walls. Alexandria’s working and middle classes lived in suburbs in the south and west of the city, and on the island of Pharos. Beyond the city walls there were cemeteries to the east and west. Here too was the Nemeseion, a temple dedicated to Nemesis, the Greek goddess of divine retribution, built by Julius Caesar to honour Pompey’s severed head.

The Heptastadion, a man-made causeway seven stades long (a stade was approximately 600 feet in length), ran from the city to Pharos Island, dividing the Eastern or Great Harbour (Megas Limen) from the less important Western Harbour (Eunostos or ‘Harbour of Happy Returns’) and the naval dockyard (Kibotos or ‘The Box’). Two arched bridges punctuated the causeway and allowed ships to pass from one harbour to the other. Offshore, on Pharos Island, shone the great white stone lighthouse that was included among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Standing over 330 feet tall, the lighthouse tower was ‘dedicated’ – either designed or financed – by Sostratos of Knidos, working initially for Ptolemy I and then for his son. Strabo tells us that the tower was made of marble and had many tiers, although the shortage of local marble suggests that it is more likely to have been made from polished limestone, while contemporary illustrations suggest that it had just three tiers: a rectangular tower, topped by an octagonal tower, topped by a cylindrical tower. On the uppermost tower stood a statue of Zeus Soter (Zeus the Saviour) and a beacon whose ever-blazing light was focused by gigantic polished bronze mirrors. However, although we have several descriptions of the lighthouse, the precise arrangement of the top tower, the all-important beacon, the statue(s) and the mirrors or lenses is not yet understood. We do know that the lighthouse was completed in

c

. 280 and stood firm until the Middle Ages. In

AD

796 the ruined uppermost tower collapsed; a century later a mosque was built on top of the second tower. In

AD

1303 Alexandria was hit by another series of major earthquakes that inflicted further damage on the lighthouse. In

AD

1326 the traveller and scholar Ibn Battuta visited Pharos and noted that the lighthouse was damaged but more or less intact. Returning twenty-three years later: ‘I visited the lighthouse again, and found that it had fallen into so ruinous a condition that it was not possible to enter it or climb up to the door’.

12

Today the fort of Sultan Qait Bey, built in

AD

1477, stands in its place.

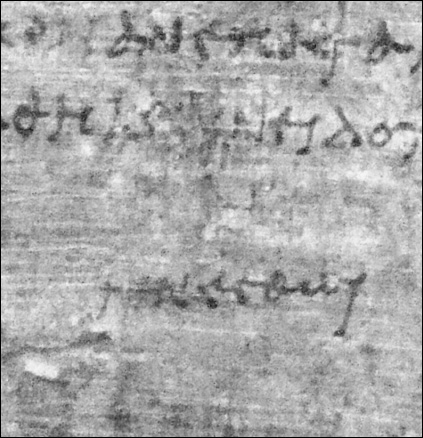

Strabo makes it clear that the Museion was a part of the wider Palaces complex. Included within the Museion was the world-famous library: an institution that could boast every book ever written in Greek, plus many foreign books in translation. The library even included a unique Greek version of the Jewish Torah, which was known as the Septuagint after the seventy Jewish scholars who had been summoned to Alexandria to work on the translation. To ensure that the library kept up to date, all visitors to Alexandria were required to hand over their own scrolls to the library copyists; the library then kept the original scroll, while its owner was presented with a hasty copy. This relentless collecting explains how, in its heyday, the library came to house upwards of half a million papyrus scrolls.

Within the precincts of the Museion the Hellenistic world’s finest scholars, many of them in receipt of government salaries, slept in dormitories, ate in dining halls and strolled through communal pleasure gardens. Relieved of the tiresome obligation to earn a crust, they were free to concentrate on the work that brought glory to Alexandria and the Ptolemies. This freedom came at a price – the scholars were expected to offer their services as and when required to the royal family, and Timon of Phleius perhaps spoke for many when he described them as ‘cloistered bookworms, endlessly arguing in the bird cage of the Muses’ – but many thought this the price worth paying. The writers of the Museion made important advances in Greek literature and language: from Alexandria came the pastoral mode (Theocritus:

Idylls

); a reinvention of the epic (Appollonius:

Argonautica

); and the development of literary theory and criticism (Callimachos, Zenodotus and Aristarchus). The Alexandrian doctors Herophilus and Erasistratus dissected and even, so it was whispered, vivisected condemned prisoners supplied by the Ptolemies, and in so doing developed a new understanding of anatomy and the workings of the brain and the pulse. Euclid wrote his thirteen-volume

Elements

, Eratosthenes drew maps and calculated the circumference of the earth, Aristarchus tentatively suggested that the earth might revolve around the sun, and Ctesibius developed the art of ballistics. And so it continued, with just one major hiccup. In

c

. 145–44, during the turbulent reign of Ptolemy VIII, the scholars were unceremoniously expelled from Alexandria, and Alexandria’s reputation as a centre of learning plummeted.