Climbing Up to Glory (30 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

“WE INTEND TO HAVE OUR RIGHTS”

Political and Social Activists

in Post-Civil War America

Â

Â

Â

Â

IN THE RECONSTRUCTION ACT of March 2, 1867, Congress unfolded its design for establishing loyal governments in the South. The former Confederate states, except Tennessee, were to be divided into five military districts administered by a major general who would be charged with the task of preparing his district for readmission to the Union. The process of readmission entailed a series of steps. Loyal voters, defined as all citizens excluding former Confederate leaders, were to be registered. They would then elect delegates to a state constitutional convention. When the new constitution had been approved by the voters and by Congress, the state would have to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. And only after the Fourteenth Amendment had been ratified by three-quarters of the states and added to the Constitution could the former Confederate states send representatives and senators to the U.S. Congress. A key component of the Reconstruction Act was its requirement that blacks be given the vote, which meant that the electorate who chose delegates to the state constitutional conventions had to include blacks. Furthermore, the new state constitutions were required to codify the same rule of suffrage for the black man. Thus, the former slaves were assured of the right to take part in the reconstructed governments of the Southern states.

Under the new state constitutions, blacks were elected to public office in all Southern states, but although they held some political power and had influence, they were never in complete control. Even in states such as South Carolina, where they constituted a majority of the population, black legislators were still disproportionately underrepresented. Whites always had the majority in the state senate, and a white man always occupied the governor's mansion. But, out of a total of 127 members in the first legislature, eighty-seven were blacks. Two blacks served as lieutenant governor in South Carolina, Alonzo J. Ransier in 1870 and Richard Gleaves in 1872. And two blacks served as speaker of the house there, Samuel J. Lee in 1872 and Robert B. Elliott in 1874. Prominent educator Francis Cardozo was secretary of state from 1868 to 1872 and state treasurer from 1872 to 1876.

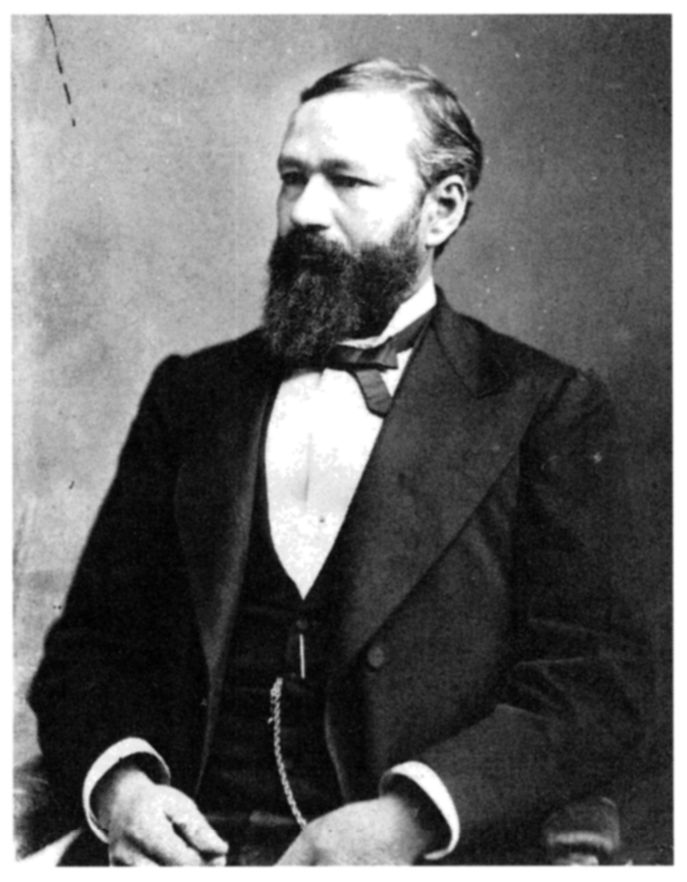

In Louisiana there were 133 black members of the legislature, made up of thirty-eight senators and ninety-five representatives, between 1868 and 1896. Most of them in office between 1868 and 1877 were veterans of the Union army and free men of color before the war. Some, however, were former slaves, including John W. Menard, who was elected to Congress but denied a seat. Three blacks, and also former slavesâOscar Dunn, P. B. S. Pinchback, and C. C. Antonineâheld the position of lieutenant governor in Louisiana. Pinchback even served as acting governor of the state for forty-three days in 1873 when Governor Henry C. Warmoth was impeached. Pinchback was the only black to serve in that capacity until Douglas Wilder was elected governor of Virginia in 1990.

P. B. S. PINCHBACK, LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR AND GOVERNOR OF LOUISIANA.

Library of Congress

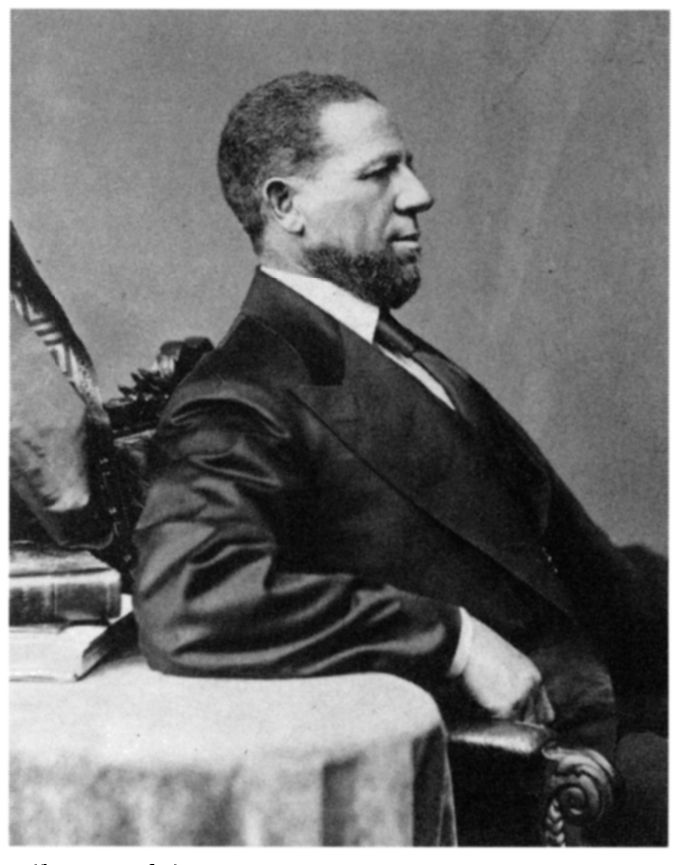

From 1869 to 1901, twenty-two blacks were active in national politics: two in the U.S. Senate and twenty in the U.S. House of Representatives. The two senators, Hiram Revels, born free in North Carolina, and Blanch K. Bruce, born a slave in Virginia, were elected from Mississippi. Bruce, who was elected in 1874, was the only black who served a full term in the Senate until the election of Edward Brooke from Massachusetts in 1966. The first of the twenty blacks to serve in the House were seated in 1869; eight were from South Carolina, four from North Carolina, three from Alabama, and one each from Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Louisiana, and Virginia. Two from South Carolina, Joseph H. Rainey and Robert Smalls, each served five consecutive terms, and J. T. Walls of Florida and John R. Lynch of Mississippi each served three terms. Like most other congressmen, many of these men had been in politics at the state level before being elected to the House. Of the twenty-two blacks who served in Congress between 1869 and 1900, ten were members of the old free black elite.

Nevertheless, at both the state and national level, the majority of the black politicians during Reconstruction had been slaves. From among this group the most influential had lived as slaves in cities, working as clerks, carpenters, blacksmiths, or waiters in hotels and boarding houses. A few had been the privileged body servants of aristocratic and powerful whites. Robert Smalls of South Carolina, for example, became the most influential and successful Reconstruction politician in the state, and Louisiana's Oscar Dunn and P. B. S. Pinchback had illustrious political careers.

1

HIRAM REVELS, U.S. SENATOR FROM MISSISSIPPI.

Library of Congress

While most black politicians held political bases in the South, at least one, George Washington Williams, served in the Ohio House of Representatives; others sat in both the Massachusetts and Illinois state legislatures. Some held various Federal and state positions, such as former Union army lieutenant James M. Trotter, who was appointed to the lucrative post of recorder of deeds in Washington, DC. Since less than 2 percent of the black population lived in the North, however, their influence was considerably less than that of their Southern counterparts.

2

Most black politicians supported civil and political rights, public education, jury reform, voting rights, and the expansion of social services, but, like the black minister-politicians, they refused to press for the kind of real economic reform that would allow unionization and give freedmen the land that they needed to build a secure economic foundation. On the issues of land reform and unionization, black politicians let down their constituencies. Far too many of the black politicians, like their white Republican allies, had narrow class-based interests supported by their own wealth. As landowners, they believed in the sanctity of private property and could not bring themselves to support the confiscation of planters' land for redistribution to freedmen. Furthermore, those among them who were employers were reluctant to support unionization, and some of them had even owned slaves. In truth, their activities in Congressâfighting, for example, for such local issues as river and harbor legislationâdid not differ substantially from those of white congressmen.

3

Robert C. DeLarge, state representative and congressman from South Carolina.

Library of Congress

On the whole, however, black officeholders were able and conscientious public servants. Extensive studies of states such as Mississippi reveal that even at the local level, where politicians tended to be ill prepared, there was little difference in the degree of competence and integrity displayed by white and black officeholders. T. W. Cardozo, the black superintendent of education in Mississippi, was convicted of embezzling funds that had been allotted to Tougaloo College, but other black politicians, such as Dunn and Lynch, had impeccable reputations.

4

Furthermore, any political corruption in the decade after the Civil War, at every level of government and in every section of the country, must be seen in perspective. The big thieves were nearly always white; blacks got mostly crumbs.

5

Most black citizens were unwilling to leave the solutions to their problems to the politicians. Now that they were free, they were determined to eliminate all forms of discrimination. They took particular aim at gaining access to streetcars and horsecars. In 1866, shortly after a group of freedmen in New Orleans blocked the passage of streetcars in the streets, local military authorities ordered the provisional governor to outlaw the separate streetcars, which had meant that the service to blacks was inferior to that provided to whites. The next year saw protests by freedmen in Charleston and Richmond against streetcar segregation. The military commander in Charleston responded by ordering an end to the discrimination; and in Richmond, where the protests had led to violence, the streetcar company gave in and announced that segregation was ended. In Louisville, freedmen embarked on a successful campaign in 1871 to ride the horsecars without discrimination, and in 1872 blacks in Savannah conducted a successful two-month boycott against the local horsecar company.

6

Black women often played key roles in combating segregation and racism, especially in the area of public transportation. Despite Sojourner Truth's notoriety, she encountered discrimination in Washington, DC, where she worked at Freedmen's Hospital after the war. While in the company of her friend, Josephine Griffing, a white woman, the conductor of a streetcar refused to stop for them. Truth grabbed the iron railing but was dragged for several yards before the streetcar came to a halt. Shortly thereafter, she reported the conductor to the president of the City Railway, who dismissed him at once. The president also told her to notify him if she were ever mistreated again by a conductor or driver.

7

In Charleston in 1867 the captain of a steamboat also picked the wrong black person to offend. He refused to grant a first-class passage to Frances Ann Rollin, one of five sisters who reputedly were among the most influential lobbyists and power brokers in South Carolina during Reconstruction. Frances took the captain to court, and he was found guilty of violating section 8 of General Orders No. 32, issued on May 30, 1867, which prohibited any discrimination “because of color or caste” in public conveyances on all “railroads, highways, streets and navigable waters.” As a result of his conviction, the captain had to pay a $250 fine.

8

Another well-known personalityâno other than Ida B. Wells, the famous settlement house worker and anti-lynching advocateâexperienced discrimination when she was forcefully removed from a whites-only rail coach in Memphis in 1883. She sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad seeking redress. Although the lower court ruled in Wells's favor, the Tennessee supreme court overturned the decision and questioned her motives in bringing the suit. In its opinion, “her persistence was not in good faith to obtain a comfortable seat for the short ride.” Instead, the court explained that “it is evident that the purpose of the defendant in error was to harass with a view to this suit.”

9

Notwithstanding the fact that Wells ultimately lost the case, it is important because she and other blacks refused to endure segregation and racism without challenging those twin evils headon.

Lesser known black women willingly stepped up to the fight. For instance, Milly Anderson won a suit in the U.S. District Court, Western District of Texas, on April 26,1875, against the Houston & Texas Central Railroad for not allowing her to board a railroad car. The judge ruled that it was illegal to deny a female passenger access to the ladies' car solely because she was of African descent. He rendered his decision on the basis of the Civil Rights Law of March 1, 1875, for which a number of black men and women had openly campaigned.

10

In another example, a Memphis teacher, Sarah Thompson, wrote to Senator Charles Sumner, who was sponsoring the act, as early as February 1872 in an attempt to convey to him the urgency for such a bill. She noted several instances in which blacks were discriminated against on public transportation. Thompson concluded her letter by thanking Senator Sumner: “the Colored people owe you a debt of gratitude which they can never repay. Long may the name of Charles Sumner live in the hearts of the Colored people of America.”

11

In some cities, groups of black citizens purchased their own means of transportation to avoid the discriminatory practices of whites. In 1866 operators of boats that ran from Savannah to Darien, Georgia, refused to take freedmen unless they remained apart from the whites. In response, several blacks, including former soldiers, formed a cooperative and bought a large boat of their own from a company in New York. The boat made two successful trips to Darien and Beaufort, South Carolina, but on its next trip, to Florida, it struck St. John's bar and was torn to pieces. It was later learned that the company had swindled the freedmen by selling them a defective boat. Since it was uninsured, the cooperative lost their whole investment.

12

Black women protested their treatment at public theaters. In response to being ejected from her seat in the parquet “white ladies' circle” of the Freement Opera House in Galveston, Texas, Mary Miller sued for damages in Federal court, which ruled that the owner, Henry Greenwall, was guilty of depriving her of her civil rights and fined him $500. In the opinion of the racist judge, the fine ought to have been just one cent, and he later dismissed the fine altogether. The black community of Galveston responded swiftly to the judge's decision. A mass meeting of outraged blacks was held to vent their anger. A larger number of the audience were of women “who were doubtless drawn out from sympathy with one of their race.”

13

That black women were active in Reconstruction politics ought not to be surprising. Although they could not vote, they could exercise influence through the secret societies that were often formed as auxiliaries to men's political groups. For example, in Richmond the Rising Daughters of Liberty was affiliated with the Rising Sons of Liberty. These groups were particularly important in generating enthusiasm among blacks during political campaigns, leading fund-raising drives, and getting black men out to vote. The wives of black coal miners from Manchester, Virginia, organized as the politically active United Daughters of Liberty and cooperated with similar groups in the area.

14

Black women in Houston in August 1868 formed two clubs: a Grant and Colfax Club, and a Thaddeus Stevens Republican club. Apparently, black women in Houston also attended black political meetings in considerable numbers. The Houston press reported in June 1869 that “80 negro women and 150 negro men were present at a meeting of Radical Republicans.”

15