Climbing Up to Glory (25 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

Often, despite their poverty, black families offered room and board to teachers to supplement their salaries. Fayetteville, North Carolina, blacks provided a house for AMA teacher David Dickson and agreed to pay for his fuel, lights, books, and assistants. When thirteen teachers were requested from the AMA national headquarters in 1866, at almost every location freedmen had agreed to assume the costs of board and fuel. The AMA had to pay only salary and transportation.

81

In addition, Dudley blacks paid Carrie Scott, a teacher, $15 per month in 1872.

82

The black thirst for education existed among the civilized nations as well. Indeed, black Indians collected money from poor but ambitious parents, built their own schools, and hired and paid teachers. A government report on black Creeks in 1866 confirmed that “they are anxious that their children shall be educated” and are “determined to profit” from “the school formed at their own advance.”

83

Throughout the South, blacks formed societies to promote education, raising money among themselves to purchase land, build schoolhouses, and pay teachers' salaries. One such society in Georgetown, South Carolina, collected $800 to purchase a lot.

84

In 1866 the Louisiana Educational Relief Association was organized to pay for the education of poor black children. Its board of trustees had the authority to lease or buy school property as they saw fit and to examine and employ teachers.

85

In 1865 black leaders established the Georgia Educational Association to set school policies, raise funds to help finance the cost of education, and supervise schools in districts throughout the state. It was established on the principle that freedmen should organize schools in their own counties and neighborhoods and finance and maintain them as well. By the fall of 1866 the association had helped finance entirely or in part ninety-six of the 123 day and evening schools for freedmen in that state and owned fifty-seven buildings. In Savannah in 1866, sixteen of twenty-eight schools were under the control of an all-black board and had only black teachers.

86

Blacks in Maryland similarly established the Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People to advance the cause of black education. It, too, was a smashing success. In 1867 it was able to build sixty schoolhouses and raise over $23,000 for freedmen's education.

87

Having established a long tradition of self-help, black churches were at the vanguard of the freedmen's educational campaign. In Texas both before and after the Freedmen's Bureau left the state, churches offered their facilities for classrooms. One of the first Bureau schools to open in Galveston, in September 1865, was held in the black Methodist church, and two other black schools that opened in the city by 1867 also utilized church facilities. African Methodists in Houston allowed schools in their churches. And as a consequence of the black community's failure to raise enough money to build a schoolhouse, freedmen in Corpus Christi in 1869 still used one of their churches for regular classes.

88

Also, in Kentucky the black First Baptist Church of Lexington, pastored by the Reverend James Monroe, opened a school in the fall of 1865, and other churches in the city such as Pleasant Green Baptist, Main Street Baptist, Asbury AME, and the Christian Church followed suit.

89

In these church-based schools, preachers often served as schoolteachers. For instance, D. C. Lacy, an African Methodist minister, taught at one of the three freedmen's schools in Limestone County, Texas, and a black Baptist pastor in Austin, Texas, taught at one of the Travis County schools.

90

Although many churches that were used as schools were poorly lit and ventilated and furnished with benches rather than desks, they were often the only public buildings owned by the freedmen that could be put to use as schools. Most people were poor, and congregations throughout the South in rural areas and small towns could afford only small, simple buildings that were sparsely furnished. A Northern teacher, G. Thurston Chase, conducted classes in North Carolina in a church that was “made of staves split out by hand.”

91

The building was totally inadequate for the large number of students, thus forcing the teacher to cram as many as seventy-five to one hundred children in a room built to accommodate about twenty-five. To make matters worse, rough pine benches served as seats.

92

Nevertheless, some places were even worse. In Marietta, Georgia, a church school was large enough, but soldiers had torn out the pews and broken the windows. As a result, the students had no place to sit, and icy winds and heavy rains blew through the room.

93

The situation did not substantially improve in towns or cities with larger congregations and sturdier buildings. Conditions were still extremely difficult, with classes typically conducted in basements that were dark, damp, and dingy.

94

Church leaders were meeting their ecclesiastical responsibilities when aiding in the establishment of schools. An important part of the moral training and religious upbringing of children pertained to their learning how to read the Bible. Operating schools would help bring about this goal as well as enable the preachers to care for the spiritual welfare of the members of their communities.

95

As a consequence of their firm commitment to education, their churches would continue to play a leading role in bringing literacy to thousands of blacks throughout the post-Civil War period, in spite of inadequate funds and facilities. By 1880, for example, the AME General Conference reported that it was operating 2,345 Sunday schools, employing 15,454 teachers and other officers, and serving 154,549. It also owned eighty-eight schoolhouses, with 1,983,358 books and pamphlets in libraries. Moreover, the other Methodist organizations and the Baptists also operated regular schools and Sunday schools. Perhaps the following comments of a journalist best express the sentiments held by church members in regard to their commitment to promote education without the help of sometimes paternalistic whites: “The Church and its schools were supported entirely by its members. It was not a âpampered favorite' of white philanthropists but âleaned upon itself for brains, money, and Christian sympathy.' White philanthropy was meddlesome and intrusive, and it provided largesse only âwhen white men stood at the helm.' ”

96

Given the limited resources of most freedmen, many of whom were homeless and barely clothed, the number of schools built and maintained and the number of teachers supported throughout the South are truly remarkable. Despite their grinding poverty, which was aggravated by the devastation of the whole Southern agricultural economy and by the frequent refusal of planters to pay black workers their wages, freedmen somehow found in excess of $1 million for schools by 1870.

97

Their actions should provide a valuable lesson for present-day blacks. If freedmen of the Reconstruction period accomplished this feat against nearly insurmountable odds, then today's blacks should be willing to help promote the education of their children by becoming actively involved in the processâassist children with homework, attend PTA meetings regularly, and volunteer a few hours each week at school. These efforts to a small extent would pay homage to the great sacrifices made by their ancestors in their struggle to obtain literacy.

The opposition of Southern whites to black education was a serious threat to the survival of freedmen's schools. Whites feared that education would give blacks the notion that they were equal to whitesâan idea that could not be tolerated in a society built on the myth of white superiority and black inferiority. Some whites regarded the teaching of blacks as a treasonous act, and others were afraid that education would prompt blacks to become more aggressive in their dealings with whites. Perhaps the comments made by an elderly white man whom Whitelaw Reid came upon capture the feelings of most Southern whites toward black education. He thought “that education for blacks was positively indecent,” and informed Reid: “Sir, we accept the death of slavery, but sir, surely there are some things that are not tolerable.”

98

This Southern white opposition to black education could manifest itself in dangerous ways. For instance, a Virginia freedman testified before a congressional committee that anyone starting a school in his county would be killed and that blacks there were “afraid to be caught with a book.”

99

Elvira Lee recalled that former slaves from Captain Hall's plantation were given an acre of land on which to build a school, but “prejudice ran so high against the negro school that this was burned after a few weeks.”

100

Thirty-seven black schools were destroyed by fire in 1869 in Tennessee alone.

101

Indeed, so many of these schoolhouses were burned down by Southern whites that former slave Pierce Harper told his interviewer that “de govâment built de colored people schoolhouses an' de Klu Klux went to work anâ burn 'em down.”

102

Frequently, freedmen would rebuild because they refused to let anything stand in their way. Education was far too important to allow it to escape their grasp.

White Southerners often attacked the freedmen's teachers, regardless of their skin color, but most of their anger was aimed particularly at black teachers. For example, a mob broke into the home of a black teacher in Delaware and frightened her so badly that she resigned from her position and left the area. White students continually harassed Martha Hoy, a black teacher in Maryland, by tripping her, pushing her off the walk, and throwing dirt and stones at her. Six whites beat a black teacher in Centerville, Maryland, and shot at him as he struggled to free himself. In Savannah, a black teacher known as Mr. Whittfield was murdered in 1866. Another black teacher, in Mississippi, watched his school burn to the ground and later was beaten nearly to death by the Ku Klux Klan. One black teacher was killed in Alabama in 1868, and there were attempts on the lives of two others. Two black teachers at Fisk University were stripped and savagely beaten by a dozen men who forced them to run through the woods as if they were animals while several whites shot at them.

103

But all of this violence would not go unanswered. Sarah Jane Foster, a white AMA teacher, for example, remembered a school meeting that was disturbed by a group of whites. However, “some of the colored people fired a pistol after the intruders, and gave chase and caught two.”

104

They discovered the names of two more, who were eventually arrested and taken to jail.

105

Southern whites ultimately would use whatever means necessary to prevent black literacy. They regularly insulted Southern and Northern white teachers of freedmen, prohibited their communities from boarding or leasing rooms to them, and beat, harassed, and murdered them. Although there was no factual basis, Sarah Foster was accused of having had sexual relations with black men. This charge was used as an excuse by a Mrs. Hoke not to board her.

106

John Trowbridge, a Northern white, noted that “there were combinations formed to prevent the leasing of rooms for schools, and those who would have been willing to let buildings for this purpose were deterred from doing so by threats of vengeance from their neighbors.”

107

John Alvord wrote about a Southern white man in Greens-borough, Georgia, being “taken out of his house at night and whipped unmercifully” for boarding a white teacher of freedmen, who was run out of town.

108

Although the above-mentioned teachers were at least spared their lives, this was not the case for a Mr. Heather, who, according to former slave Evie Herrin, was tied to a log by a group of whites and shot to death. This assault led to the Clinton race riot.

109

With the constant and often violent opposition of whites to the education of blacks and with the chronic shortage of financial support for freedmen's schools in the late 1860s and throughout the Reconstruction era, these schools fell on hard times. The condition of the already weakened economy was worsened by the economic depression of the 1870s, and the Freedmen's Bureau and Northern benevolent societies withdrew their financial aid. As a result, many of the schools organized by freedmen themselves were forced to close. But they persisted in their quest for education. There was much work to be doneâmore qualified teachers had to be hired and retained, school buildings had to be secured and maintained, and supplies had to be found. To these ends, freedmen labored diligently. In so doing, they not only continued the tradition of educational self-help but also became the first Southerners to wage a campaign for universal public education. With the help of the Freedmen's Bureau and Northern benevolent societies, the campaign grew from a meager beginning in 1860 to a school system that was virtually complete in its institutional form by 1870. In other words, the freedmen's schools served as the precursors of the new public schools that were in operation throughout the South by 1870.

110

Indeed, this accomplishment is a fitting tribute to the struggle made by black men and women to become literate.

The issue of higher education was the concern of numerous blacks, the Freedmen's Bureau, and Northern benevolent societies. As was the case in regard to creating and maintaining grade schools, the three groups again united their efforts and established and supported several institutions of higher learning for black men and women during the Reconstruction years. Black churches, too, often played a leading role in founding and supporting black colleges and universities. Although the AME Church did not found Wilberforce University it purchased it in 1863, and Bishop Daniel Payne became the school's president.

111

Northern Methodists founded Claflin College in 1869 in Orangeburg, South Carolina,

112

and Bennett College for black women was opened in 1873 in Greensboro, North Carolina, by Methodists, although the college was the inspiration of newly emancipated slaves who had bought the land on which it now stands.

113

During the post-Civil War period, black Baptists, with the assistance of their white brethren, helped establish and support Spelman College for women in Atlanta, Benedict College in Columbia, Leland University in New Orleans, Shaw University in Raleigh, and Morehouse College in Atlanta.

114

Saint Augustine's College was opened in Raleigh in 1867 by the Episcopal Church, and in the same year in Concord, North Carolina, the Presbyterian Church founded Barber-Scotia College.

115

The Congregational Church, working through the American Missionary Association with the aid of the Freedmen's Bureau, also founded numerous schools for blacks during the Reconstruction era. Among these were Fisk University in Nashville in 1865; Howard University in Washington, DC, in 1867; Atlanta University in Atlanta (now Clark-Atlanta University) (1867); Talladega College in Talladega, Alabama (1867); Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia (1868); and Tougaloo College in Tougaloo, Mississippi (1869).

116

Finally, Fayetteville State College was established in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1867 through the joint efforts of seven blacks and the Freedmen's Bureau. The black citizensâDavid Bryant, Nelson Carter, Matthew N. Leary, A. J. Chestnut, Robert Simmons, George Grainer, and Thomas Lomaxâpaid $140 for a lot on Gillespie Street for the sole purpose of providing education to blacks. In accord with their desire, General Howard of the Bureau erected a building on this site.

117

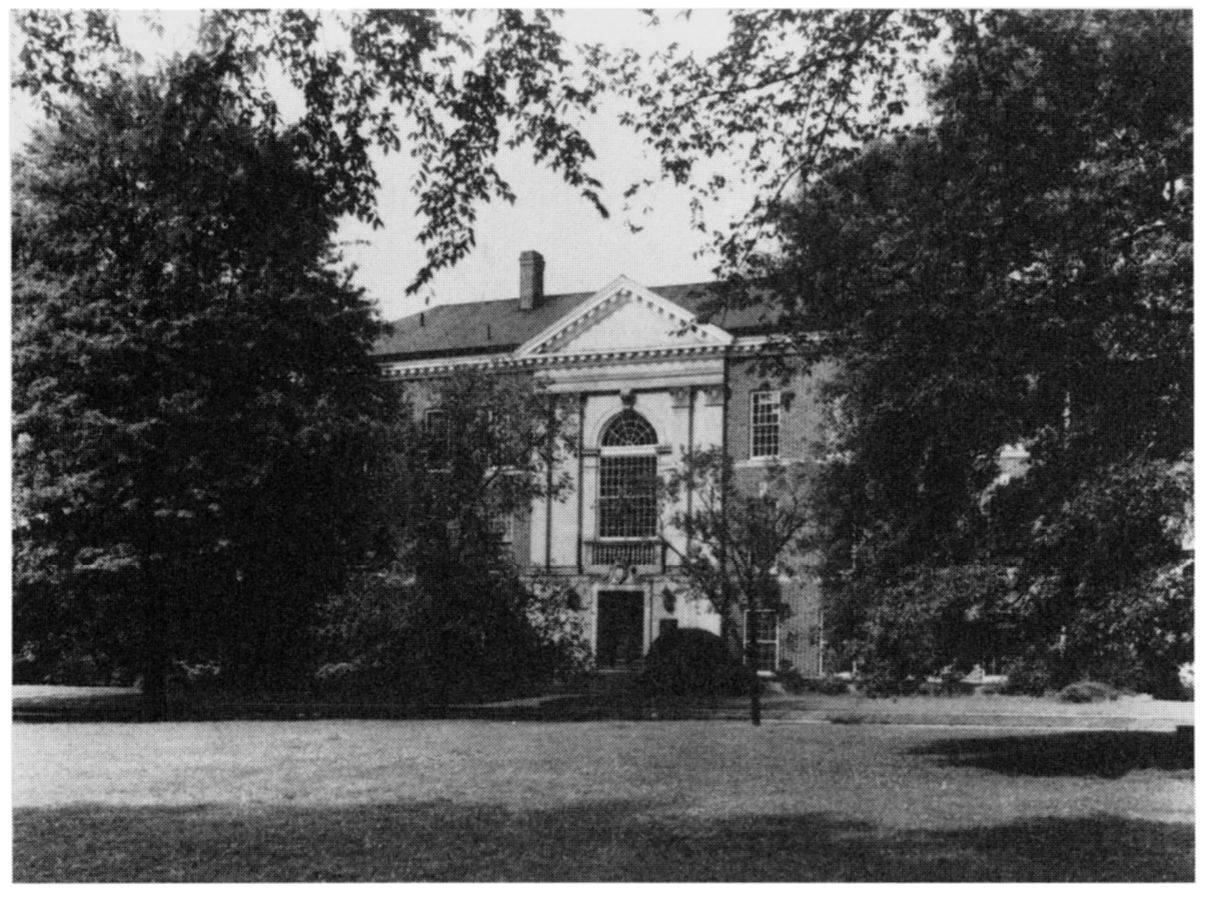

LAURA SPELMAN ROCKEFELLER MEMORIAL BUILDING, SPELMAN COLLEGE.

Courtesy of Archives/Special Collections, Atlanta University Center, Robert W. Woodruff Library

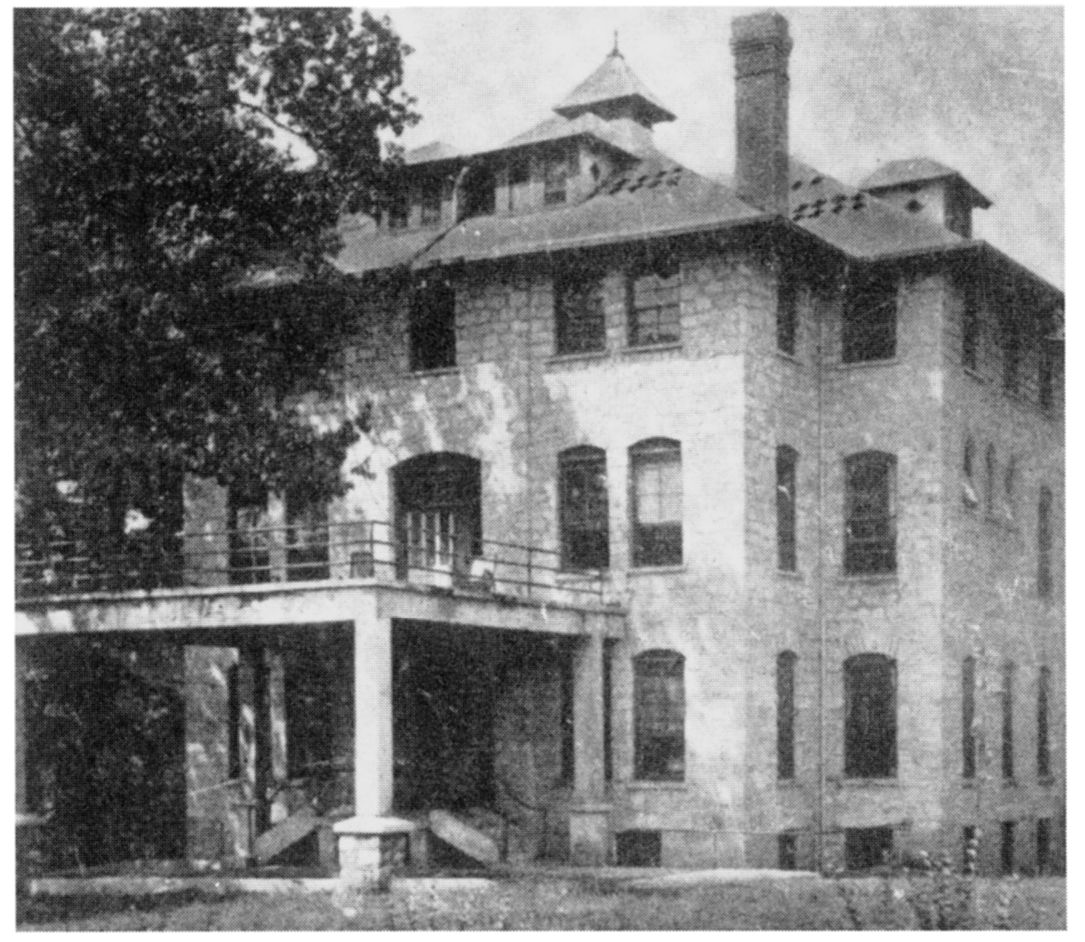

SAINT AUGUSTINE'S COLLEGE

Courtesy of the Archives Division, Saint Augustine's College

HOWARD UNIVERSITY, 1870.

Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, 1934.

Courtesy of Archives/Syecial Collections, Atlanta University Center, Robert W. Woodruff Library

The priorities of these institutions varied to some extent from school to school. The goal at Atlanta University, Tougaloo College, Fayetteville State College, and Wilberforce University was the training of teachers to instruct the growing numbers of black students.

118

And, although Howard University, Saint Augustine's College, Lane College, and Fisk University sought to train religious leaders, they, too, had as their priority the training of teachers.

119

Others such as Shaw University and Livingstone College focused primarily on educating religious leaders for black communities.

120

Some of the private schools also concentrated on teaching morality, discipline, and responsibility as the means toward developing good character. Hampton Institute, in particular, under the leadership of General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, adopted this approach.

121

Moreover, while most of the black schools developed a Liberal Arts curriculum that included Greek, Latin, English, French, Philosophy, Astronomy, Chemistry, Geology, Political Economy, History, International Law, Mathematics, Geometry, Trigonometry, Algebra, and Logic,

122

Hampton's curriculum emphasized industrial education and focused specifically on instructing its students in manual labor. Such courses as brickmasonry, printing, cooking, sewing, basket weaving, broommaking, stock raising, dairying, farming, tinning, tanning, blacksmithing, wagon-making, carpentry, painting, barbering, and steam-power sawing were offered.

123

Most of the black colleges and universities were open to whites, although very few whites were enrolled, and most of them were also coeducational, which fit in with a larger national trend. In 1872, for example, there were ninety-seven coeducational colleges and universities in the United States.

124

The historical record is sparse in terms of how female students were treated in these schools. However, we do know that Mary Ann Shadd Carey withdrew from Howard University's law school because of her gender in 1871. She eventually returned and earned a bachelor of law degree from Howard in 1883.

125

Since teaching was one of only a few professions open to black women, the vast majority of those enrolled sought degrees in education. Most of Atlanta University's female graduates, for example, either taught in Atlanta's public school system or in private schools. Mary Pope McCree, a member of the graduating class of 1880, ran a private school at Big Bethel AME Church until the Reverend Wesley Gaines recruited her to serve as the principal at Morris Brown College. Despite her success, private schools often lacked the funds for current books and teachers aides, and salaries remained meager. Moreover, most public school systems did not hire black men and women as teachers. It was not until 1878, for example, five years after the first Atlanta University teachers graduated, that five of them were hired by Atlanta's Board of Education. They were Indian Clark, Ella Townsley, Julia Turner, Mattie Upshaw, and Elizabeth Easley, all black women.

126

Although the evidence is limited, it is plausible to suggest that a disproportionate number of the earliest black enrollees at these colleges were from the middle class. When Hampton Institute opened its doors in 1868, for example, most of its fifteen students were drawn from the village's black elite, including the family of the prominent William Roscoe Davis.

127

And, given Atlanta University's stiff admission requirements, it is unlikely that many students from the lower class would have been able to meet these standards. We also know that, like Amanda Dickson and Adella Hunt, many of the students from Hancock and the surrounding counties who attended Atlanta University during its first decade or so either had been nominally free before emancipation or at least shared surnames and other connections with prominent white families from their home county. Among this group were Matilda Rogers and Linton Stephens Ingram from Hancock County, Tolbert Bailey from Warren County, John Wesley Marlow from Milledgeville, and Fannie and Quinnie Stephens from Crawfordville. These individuals were so light-complexioned that they were virtually indistinguishable from most whites. Moreover, unlike the vast majority of people of color in Middle Georgia, many families of the Atlanta University students had also accumulated some personal and real property in the years following the war. Certainly, free status prior to the war, association with prominent families in the white community, and ownership of at least a small amount of money and property combined to create an undeniable advantage in gaining access to a better education during Reconstruction.

128

We also know that Howard University's admissions requirements were steep in comparison to other black colleges, and that although Howard was not a true university placed up against most white schools, it reigned supreme among the black ones. No other black college offered as comprehensive a curriculum as did Howard. Furthermore, Howard was also opened to white men and women and expected to enroll some of them as well. It was thus unlikely that many blacks from the lower strata of society would measure up to the Howard standard. Indeed, a quick perusal of the historical record seems to bear out this assumption. A number of Howard's earliest students were from the black middle class, and three prominent families in particularâthe Wormleys, Shadds, and Shippensâfirst were represented by these graduates. Two members of the Wormley and the related Shadd families, who have served Howard University and the Washington community in many important positions, were Anna Wormley, Class of 1870, and Eunice B. Shadd, Class of 1872. The Shippens, prominent especially in the public schools of the District of Columbia, were represented by Fannie Shippen, Class of 1870.

129

Financial support for higher education flowed from various sectors of black communities. It came from religious bodies as well as from the individual and joint efforts of black men and women. Not only did black Baptists support higher education for men and women, but so, too, did the AME Church. Since they viewed women and ministers as important agents of cultural change, their educational status was of great concern to missionaries. Bishop Payne reasoned that since women were mothers, wives, and teachers, they played critical roles in shaping and transmitting the culture of the race. Furthermore, in his opinion, those roles took on even greater significance as African Methodists considered the task of regenerating the freedpeople. Therefore, Payne reached the conclusion that “the future demands educated women, ... who will give unto the race a training entirely and essentially different from the past.” He further clarified the mission of black women as one in which the demands of the new era required them to “descend into the South as educators.” Richard Cain, an AME minister, underscored the sentiments of Payne when he asserted: “We need, and must have schools for girls.”

130

Although there is no record of the AME Church establishing institutions of higher education for black women, there is no concrete reason to doubt its sincerity in terms of educating them, since schools begun by the AME Church such as Allen University, Morris Brown College, Edward Waters College, Paul Quinn College, and Wilberforce University (which the church purchased in 1863) all enrolled black women.