Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (37 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

As I sweep, I realise that this is the first time for a year I’ve felt motivated to do anything that’s not absolutely necessary, and I know that a little shift has occurred. It gives me hope that maybe, if more little shifts start to happen, I might get better.

From that day, when I realised I’d got up off the sofa and was sweeping the kitchen, it took ten years until I could honestly say: ‘I am well.’

I think I’ll go back to the gym. I sit on the exercise bike and picture a phoenix rising out of the ashes to give myself a boost. I set the resistance level to 1 – the easiest setting – I used to be on 10 but I need to give myself time. The bike doesn’t bloody work. The pedals won’t go round. I flap my hand at an instructor as he wanders past. ‘Excuse me, excuse me.’ He comes over, has a fiddle with the controls, says it seems to be all right. I slide off and he hops onto the bike to test it. The pedals go round. I climb back on, the pedals don’t go round. I’ve got nothing. Nothing in my legs.

London is full of bad memories; Hubby and I think it might help me get better if we move to the coast – the fresh air, slower pace of life – and it will be good for our daughter too. I sell my guitars – it surprises me how pleased Hubby is that I’m selling them – but I don’t throw away my picks. I keep them in my ladylike purse. I like seeing them every time I get money out; a gold one with a serrated grip and a heavy-gauge pale grey one.

Hubby and I view a house by the sea. To get to it we have to walk up a narrow dirt track, across a wooden bridge – where we pause and look down into the stream as two swans sail underneath us – past lilac bushes and an apple orchard, a row of flint fishermen’s cottages, until we come to a white clapboard A-frame beach house, like an American holiday home from the fifties, perched on top of a slab of rock that drops away to the English Channel. The white shingle path to the front door winds around enormous sword plants and yuccas – just walking up the path is an adventure – but as we round the last bend, we come across a rabbit splayed out on the doorstep, its throat and stomach ripped open. The estate agent scoops the limp carcass into a plastic bag in one deft movement. I step over the entrails and joke that maybe this is a sign we shouldn’t buy the house. We enter the large white open-plan living room and straight ahead, as if there’s no wall, is sea sea sea. We decide to buy the house, sign or no sign.

13 HASTINGS HOUSEWIFE REBELS

2007

I promise myself I will do two things when we move to the coast:

1. I will do a class at art college.

2. I will get fit.

I sign up for a ceramics course one afternoon a week at Hastings Art School. My husband is annoyed, I don’t understand why. Perhaps he’s jealous. I register him for a life drawing class, so I’m not the only one having fun. I choose ceramics because it fits in with my daughter’s school timetable and, since the cancer treatment, my hands are so shaky I probably can’t draw or paint any more. This is the first time I haven’t agonised over a decision. The other people on the course are a mixture of old and young, un employed, part-timers and loners, like me. I love them. They’re clever and interesting. I love their conversations. They discuss hearing aids and the war. ‘Women used to put a box of Omo washing powder in the window to signal to the American GIs, “Old Man Out”.’ They make me laugh. Coming to this class once a week is healing. I feel relaxed and comfortable for the first time in a decade. Best of all is the teacher, Tony Bennett –

When the student is ready, the teacher appears

. A good teacher is a gift, they bring a subject alive and that’s what Tony does for me. He watches me for a couple of months, like I’m a nervous animal. He doesn’t get too close. Occasionally he appears behind me – the way art teachers do – and makes a comment about my interpretation of a subject; he never criticises, never picks at my technique, always talks about the emotion in the work, until one day, when we’ve become relaxed with each other, he says gently, ‘Viv, why don’t you try expressing

yourself

in your work?’

I’m horrified. I’m surprised at the vehemence of my response. ‘I don’t want to express myself! I’m sick of expressing myself! I’ve expressed myself to death! I just want to make nice brown pots to put in the living room.’

He lets me blow off steam and leaves it at that. Next week he comes up to me and says, ‘I know why you said that, I heard you on Radio 4 last night, it was a different surname but I recognised your voice, you’re Viv from the Slits.’ (It was a rerun of an old interview.) We talk about the Slits and how hard it was being a girl who forged the way, who took the knocks every day on the street and in the industry and that now I just want to be invisible.

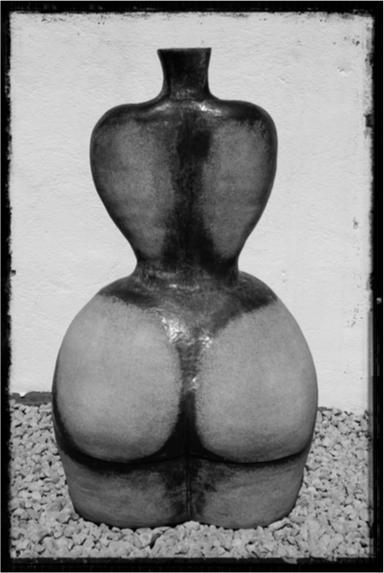

But he’s sown a seed, something in me changes and I let go. I create my first piece of real work. It’s like the work I used to make at art school when I was seventeen; erotic and a bit funny, combining ancient and modern, fertility symbol and fetish. I take it home. Husband doesn’t like it. He sneers at it, says he won’t have it in the house, ‘Put it in the garden.’ He also says our daughter mustn’t see it because it’s sexual. It’s not sexual, it’s a representation of a naked female. I think children can make the distinction between entertainment, art, humour and real life from a pretty young age. Do all artists who draw life models have to hide them from their children? Of course they don’t. What about artists like Yoko Ono and Louise Bourgeois? They make extreme work and both have children. Not that I would ever call myself an artist. I wouldn’t dare. But I’m not going to hide my real self from my daughter any more. This is what her mother is doing. If she’s got any questions or worries about it, she can come and talk to me. I put the ceramic on the sideboard.

Husband works all day in the open-plan kitchen/living room, the one room we have apart from the shared bedroom. He still has a studio in London, but won’t ever go to it. He’s becoming very insular and curmudgeonly out here in the country. I’m beginning to wonder if moving was such a good idea.

My first ceramic, 2007

I’m craving my own space, so I rent a studio (which I offer to Husband, but he’d rather work at home) in Hastings with a fellow student called Robin, and I go there every day for a couple of hours – after dropping my daughter off at school – to work on my ceramics. I don’t like touching the clay at first. It’s too squelchy, gets under my fingernails and messes up my clothes. It takes a couple of weeks before I can plunge my arms deep into the big clay bins, right up to my elbows, and grab fistfuls of the stuff and slam it onto a bench. I find kneading and pummelling therapeutic – I never would have chosen this medium if it hadn’t been for my circumstances, but now I’ve found it, it’s just what I need. The shaping and moulding, scraping and smoothing are very natural, organic actions, you only have to half concentrate, so a little bit of your brain is unaware of what you’re doing, letting the instinctive, intuitive part come forward. This is good for me, it gives the hamster on the wheel inside my head a rest.

My daughter comes home from her new school in tears. She came last in the cross-country race. She says she doesn’t mind not coming first, but she can’t bear coming last. I say it’s because you haven’t practised. No one can do anything well if they haven’t practised. Let’s practise together. We run round the field next to our house every evening after school. It’s muddy and lumpy with mole hills; there are boggy patches with reed beds that we have to leap across; startled sheep trundle out of our way; little piles of sheep poo are dotted around like mounds of Maltesers. She trots off, but I can barely walk. My asthma is so severe I have no breath, no lung capacity. My legs are tired after a few steps, she goes round twice to my once. I hate running. After a couple of months my daughter comes third in the cross-country race (subsequently she opts to stay at the back with the cool girls) and I decide to start trying to run along the top of the sea wall, see if it’s a bit easier running on a flat surface. I’m like Rocky at the beginning of the movie, out of breath, falling onto each foot, no control, I remind myself of the pensioners I’ve seen on TV at the end of a marathon. I manage a quarter of a mile but I’m dizzy with lack of oxygen. I lean on a flagpole panting for a few minutes before turning round and half running, half walking back home. Gradually, I improve, the asthma clears up, I can feel my muscles firm up and I start to love running. It’s like a meditation to me, I

have

to do it; I don’t even notice the effort any more.

I run in all weathers at all times of day; rain, cold, dark, hot. On one side of the sea wall is a road and flat fields of tall grass. I watch the swans gliding along a little canal, which was built to ferry ammunition up and down the coast on barges during the First and Second World Wars. I wave at the shepherdess driving her tractor, long blonde hair whipping around her brown face, her collie eager and alert on the passenger seat. On the other side of the wall is the sea; the grey waves roll onto the pebbles, gulls squawk and dive, and in the far distance Dungeness power station is lit up like a floating gin palace, perched on the horizon. These days I cruise past the quarter-mile flagpole and after two miles of straight running I reach the beach cafe at the end of the wall – its front door propped open with a tub of margarine – no need to rest now, I turn my face into the wind and head back.

The paranoia I was left with after the cancer – that I would get ill again – is beginning to lift. For a while I kept going back to the hospital, thought I had this, that and the other. They were very patient and tested me for everything; I swallowed tubes for them to look into my stomach, had loads of blood tests for food allergies, then they stuck a camera up my arse … that one finished me off. I think I almost had a touch of Munchausen’s Syndrome (hospital addiction syndrome); I couldn’t leave the safety of the hospital and all the attention and ritual behind. But a camera up your arse will sort that one out.

After so long worrying and being fearful, living by the sea and running is giving me the mental space to think creatively again for the first time in years. With the salty wind on my face, feet pounding on the shingle, Kate Bush,

The Hounds of Love

, on my iPod, new thoughts enter my head.

What do I think about that architecture?

as I run past a white modernist house: ‘I like the shape of the house but the windows are too small.’

What do I think of the asymmetrical stairs, the sculptures in the garden?

‘Those stairs don’t look right with the house; the sculptures are interesting.’

Who am I now? Am I the same person I was when I was seventeen? The person I was when I married? Or has my personality been completely eroded and I must start again, creating myself from scratch, like an amnesia victim?

It doesn’t matter what the answers to the questions I’m asking myself are, how uncool, how ordinary; they just have to be the truth.

Each morning I start again with the questions, easy stuff, like colour – I’ve always been drawn to colour. Mum made colour interesting for me, when I was little; she would say, ‘See the colour of that woman’s skirt? That’s called elephant’s breath.’ Or, ‘See that ribbon? It’s mint green, this one’s duck-egg blue, that flower is dusty rose, and that one’s salmon pink.’ I interview myself as a way to discover the new me.

What colours do you like?

‘Eau de nil, pale, calm and mysterious; mauve and lilac, delicate, gentle, sensual.’

Why do you like those colours?

‘All I could think about after chemo was the colour purple, I decorated the whole Christmas tree in purple and wrapped every present in purple, it felt healing.’

Good, there’s a story there, a meaningful answer. Make a story out of your experiences

.

I’ve started to laugh again too; mixing with the non-judgemental people at art college, I realise I’m quite playful. I reignite my love of detail in clothes: a puffed sleeve, a side or a front zip on a leather jacket, the shape of a heel or toe of a boot. I’m enjoying looking: I used to look at everything and everyone. I notice marks on a stone, the haggard sea-worn groynes;

it doesn’t matter what you like, just be truthful and observant

, I tell myself. I don’t let myself off the hook; if I make a statement, I have to justify it.

Running also helps me accept my body. After all the years of medical intervention, I feel violated. All those unknown men’s hands up me for years. To cope, I reacted like a rape victim, disowning my body, floating above it, not

in

it whilst it was happening. I would chant to myself, ‘I’m doing this for a baby, I’m doing this for a baby. I’m doing this to get well.’ At last my body is beginning to feel like it belongs to me again and it’s strong and healthy, serving me well instead of constantly letting me down.

I’m also trying to learn to play tennis. It’s not me, I’m hopeless at it, but I want to fit in with the other mothers. I swing my arm listlessly as the tennis coach lobs me a ball. ‘I wish a man would come into my life to inspire me,’ I say to her. Where did that unfaithful, insurgent little thought come from? I’m shocked at myself. I haven’t strayed, even mentally, in all my fifteen years of marriage. And now it’s occurred to me I need a muse to get me going, someone in my head to make me step up, give me some inspiration.

Be careful what you wish for

.