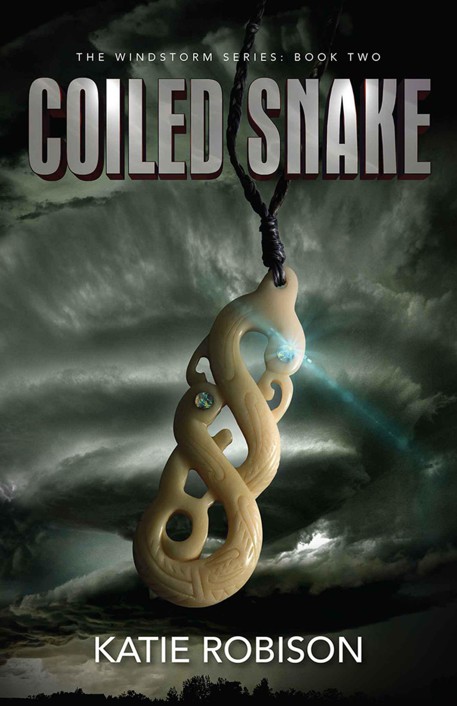

Coiled Snake (The Windstorm Series Book 2)

Read Coiled Snake (The Windstorm Series Book 2) Online

Authors: Katie Robison

Copyright © 2013 by Katie Robison

All rights reserved. Published by Quil Books, Inc.

No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

First Edition: November 2013

ISBN: 978-0985046538

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance of characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Quil Books, Inc.

For Jonathon, Emily, and Christopher.

Ko tō ngākau ki ngā taonga o ō tïpuna hei tikitiki mō tō māhunga.

And for Linda. Happy Birthday.

Because of its circular shape, the cyclone received its name from the Greek word κυκλως, which was mistakenly believed to mean ‘the coil of a serpent.’

Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me!

A fine wind is blowing the new direction of Time.

If only I let it bear me, carry me, if only it carry me!

If only I am sensitive, subtle, oh, delicate, a winged gift!

If only, most lovely of all, I yield myself and am borrowed

By the fine, fine wind that takes its course

through the chaos of the world

Like a fine, an exquisite chisel, a wedge-blade inserted;

If only I am keen and hard like the sheer tip of a wedge

Driven by invisible blows,

The rock will split, we shall come at the wonder,

we shall find the Hesperides.

— D.H. Lawrence

The boundary that separates two masses of air is known as a weather front. A single disturbance in the front can lead to the development of a cyclone.

The Māori people say that in the beginning there was only darkness. From that stillness our first parents came forth: Ranginui, the Sky Father, and Papatūānuku, the Earth Mother. Ranginui and Papatūānuku drew together and created many children. To let light into the world, these new gods decided they must separate their parents. Tāwhirimātea, the god of winds and storms, was the only child who protested. His brothers ignored his objections, and when Ranginui and Papatūānuku were torn apart, their cries stabbed Tāwhirimātea’s heart. He promised his siblings that from that day forth they would have to deal with his anger.

When my eyes blink open, all I see is a yellow spot on a flaky beige backdrop. It takes me a moment to realize I’m looking at a stain on a cracked ceiling. I lie still and stare at the stain, trying very hard to decide where I am.

I’m in an old house

, I realize. It’s the smell that tells me—damp walls, rotted wood, a bland odor like boiled vegetables. There’s something familiar about that smell, but the harder I think about it the less familiar it grows. Am I at the home of one of Sue’s friends? Maybe Rose down the street?

I lower my gaze to look at my body. I’m wrapped in wool blankets on a bed that takes up practically the entire room. Just below my chin I see the red of my shirt. I wiggle my fingers, and my hands tell me that under the blankets I have on corduroy pants.

I don’t own corduroy pants. Or a red shirt.

Slowly, I turn my head to the side. The beige plaster on the wall in front of me is peeling. A framed sketch of a gray bird hangs off-center. In another room, I hear the shrill scream of a kettle boiling over. The angry noise makes it very hard to think.

I turn my head the other way. Beside me is a glass door leading to the outside. I sit up slowly—my brain seems to pitch against my skull—and push aside the blankets. My arm stings, but I ignore it. I ignore my legs too, the sudden pricking in my pulse, as I carefully lower my feet to the ground. An inexplicable dread is growing in my stomach. I still haven’t figured out where I am. But I have a feeling I need to get out of here.

I slide open the glass door and hobble into the sunshine. After a few blinding steps, I realize I’m on a dirt path and that directly ahead of me is a large body of water.

Am I at the lake?

Maybe I got tired and someone let me take a nap in their cabin. But I’ve never been to this part of the shoreline; I don’t recognize a thing. Where is Sue? Jack and Maisy? Why did they leave me alone?

I curse as I step on something prickly and lift up my foot, tripping over logs and rocks. And then suddenly my toes are sinking into softness, and the slamming sound of waves is rushing into my ears. I get a mouthful of pungent salt as I turn my head to face an endless expanse of gray sand, strewn with driftwood and backed by dunes of spiky shrubs.

There are no beaches like this in Minnesota.

I stagger toward the pounding water, hundreds of questions clogging up my mind, the dread in my gut growing exponentially. I look around desperately for something to tell me where I am. A sign, a person, a newspaper. But there’s nothing.

And then I stop and squint at the sand, my pulse rising in my ears. On the beach, directly in front of me, is a footprint.

I continue to stare. Something isn’t right. I look up and down the shoreline, but I don’t see any other tracks. How is that possible? I’m too high up the beach for the water to have erased any impressions. No one could have left an isolated print like that.

No one, except …

“Kava.” I stumble backward and trip again, this time falling to the ground. My elbow smacks a rock, and I cry out from more than the pain. It’s all surging back now. Winnipeg. The camp. Rye. The fortress. The bomb. And, them.

I have to get out of here!

I stand up, forcing aside the protesting throb in my leg.

But when I raise my head, I freeze. Standing on the beach behind me, only a few yards away, is a tall woman with gray hair flowing in the wind. Her hands are on her hips, and black tattoos snake down her chin and left arm. She says nothing. Just watches me with shadowed eyes.

We stare at each other as the sea air hisses in our faces. I hold perfectly still, knowing the wrong move could mean my death: I see the strap for a holster on her back.

Finally, she speaks. “Tea’s ready.”

I gape at her as she turns around and walks back up the path to the house. Unsure what to do, I continue to crouch in the sand.

When I can no longer see her, I look the other way down the beach. It’s still deserted. Do I dare make a run for it?

I stand up and take a cautious step forward. Immediately, a sharp pain shoots down my leg. I bend over to clutch it, but the movement sends a stabbing sensation into my arm as well, and I curse.

Quickly, I roll up my right pant leg and discover that the skin underneath is covered in gauze. I pull a corner of the bandage away and carefully unwrap my ankle. Beneath the dressing, my once brown leg is a pale pink, smeared with large yellow bruises and thick scabs. I draw in a breath through my clenched teeth and retie the bandage. Instinctively, I reach out to the wind. I’m not going to be able to run, but maybe I can get away if I windwalk. I inhale the sharp salt air into my lungs, feeling for the strongest current. Making my choice, I form

honga.

Only I don’t. Frowning, I try to cement the bond, but the wind slips away, taunting me as it rustles the grasses on the dunes. I try again and again, but it’s as if I walk into an invisible wall each time. I can see and feel the wind, but I can’t hold it.

I look back toward the house and jump when I see the woman standing on the path again.

“You might not want to take too long,” she says. Her accent is alarmingly familiar. “It can get dangerous out here.”

Gritting my teeth, I hobble across the sand and follow her reluctantly back to the house, keeping a safe distance between us. She waits for me in the front doorway, and when I get close, she turns around and walks inside. I follow her through a dark, narrow hallway into a tiny kitchen with a small stove, a sink, and only two cupboards. She motions for me to sit at a fold-up table, draped with a threadbare cloth. I sit, wincing. She pours some tea into a cup missing its handle and places a sandwich on a chipped plate. Then she opens a box of cookies and sits down herself, cup in hand.

I take a sip of the tea. It has an unpleasant, bitter taste, but I’m thirsty, so I take another, keeping my eyes trained on the tablecloth.

When is she going to kill me?

My hand shakes, so I set the teacup down.

“I expect you’ll want your sling.”

“What?” I look up.

“For your arm. You left it in your room.”

I stare at the tattoo curving under her lower lip and look down quickly. My fingers twitch in my lap.

“I’m no doctor,” she says, “but my guess is you’ve done some damage scampering over the beach like that. You’re not really supposed to be back on your feet for another week or so.”

I shift my weight, conscious of the growing pain in my leg and the roiling in my gut. I clench my jaw and ask, “How long have I been here?”

“A few days now.”

That can’t be right. My injuries must have had some time to heal, or I wouldn’t have been able to walk at all.

Why are they letting me heal? Do they want me to be healthy before they torture me?

“It took them a while to get you here.”

I take another shaky sip of tea, a sickening dread creeping into my chest. “Where is here, exactly?”

“Okarito.”

“Where’s that?”

“New Zealand.”

I gape at her, and she laughs. “Don’t have a heart attack, girl. Where did you think you were?”

“I don’t know,” I mutter.

This can’t be happening.

“How did I get here?” I ask.

She waves a hand. “I don’t know the details. I imagine they kept you under for most of the trip.”

I slump back in my chair as a slew of elusive, half-formed memories surfaces in my head.

Sleeping fitfully but unable to wake up. Choking down food and drink but unable to taste anything. Being ordered to go to the bathroom but unable to really see where I am.

I clamp my arms around my stomach, feeling even more vulnerable and afraid than I was before—and trying to ignore the sudden sensation that I need to pee.

The woman pulls a flask out of her pocket and pours something into her cup of tea. “My name’s Miri,” she says, screwing the lid back on. “You’ll be under my watch for a while, until they come to get you.”

Who’s coming to get me? More Rangi?

Images of Jeremy’s bullet-ridden body and Charity’s scorched corpse swirl in my mind, and I can’t get my voice to ask the question.

“I suggest you take it easy for a bit and get plenty of rest,” she continues. “Your room’s down the hall. So’s the loo.”

At her mention of the bathroom, the need to relieve myself increases. But as I look at her face again and see the black ink curving onto her brown lips, all I can think about are the tattooed faces of Aura’s attackers and how they looked right before they slashed her throat.

“Why?” I gasp. “Why am I here? What do you people want with me?”

“You’re here because I don’t live with a

hapa

,” she says. “So this business can be kept quiet. Care for another sandwich?”

I look down at the table, excruciatingly aware that she didn’t answer my question.

“Right,” she says. “Well, I have to step out for a bit. Try to get some sleep.” She slips on a pair of gray gumboots, grabs a shockingly bright yellow scarf from a hook on the wall and wraps it around her neck, then walks out of the room. I hear the front door open and close behind her.

As soon as she’s gone, I push off the table and stumble down the hall.

Stay calm. Breathe.

But I can’t stay calm. I’m halfway around the world from home. A prisoner of the Rangi. Who knows what they’re going to do to me?

Calm down. First, find the bathroom.

It doesn’t take me long to spot the lavatory at the end of the hall. I quickly use the toilet and then wash my hands, glancing at my reflection in the mirror as I do so. A girl I don’t recognize looks back at me. Her long face is leaner, black hair thicker and wilder, almond eyes more hollow and knowing than the girl who left the small town of Williams, Minnesota a few months ago.

The pink scar on my cheek seems to leap out of my brown skin—a scar I got from a Rangi’s bullet.

I need to get out of here!

In the mirror I notice a framed map of New Zealand hanging on the wall behind me, above the towel rack. I turn around and look for Okarito. When I find it, I curse. It’s a tiny dot on the west coast of the South Island, miles away form the nearest city.

How am I going to get out of here?

I’ll figure that out later. I’ve been here too long already.

I limp hurriedly down the hall toward the bedroom that Miri says is mine, passing one other door on my way; I try the handle, but it’s locked.

In my room, the only furniture, apart from the bed, is a small nightstand. I search the drawers for something useful, but there are just clothes—more faded corduroy and woolen sweaters—and some old paperbacks. Nothing I can use as a weapon.

I look outside. The house is probably being watched, but it’s worth the risk. Better than waiting here for them to quietly torture and kill me. And if I act now, maybe I’ll catch them by surprise.

As I falter toward the door, I spot the sling hanging on a peg and clumsily pull it over my head and shoulder. It feels better to have my arm held against my chest, but now I only have one hand.

It doesn’t matter. If they catch me, I’m dead anyway.

For the second time, I slide open the glass door and blink my way into the salty air. I immediately reach for the wind, but just like before, it remains evasive. I can see every airy tendril, but I can’t connect to any of them.

I clench my fist. I don’t have time to think about why I can’t form

honga

. I have to focus on getting out of here.

As I stagger down the path that runs alongside Miri’s house, swiveling my head to look for potential assailants, my mind replays the terrible things the Rangi did, how they murdered the families at the

Wakenunat

, tried to blow up the entire fortress. If I remain their prisoner, I’m done for.

The bombs!

Kava!

Do they know? Is

that

why I’m here? If that’s the reason, I really am screwed.

How did they catch me anyway? I can’t seem to remember. The explosive must have gone off before I got away, which is why my leg looks like hell—and why my arm needs a sling.

Suddenly, the image of a Rangi warrior with long, black hair and a gap in his teeth standing over my bandaged body materializes in front of me, and I trip on Miri’s gravel driveway. The warrior’s leering grin bursts into black spots that swirl in my vision.

But now I remember something: the warrior told me they didn’t kill me when they found me because of my necklace. He showed me how the design on the pendant matched the awful tattoo on his chest. And he knew my name.

I reach under the collar of my sweater for my necklace, but it’s not there. Instead, my fingers find a thick metal chain locked closely around my neck. Attached to the chain is a large stone ring decorated with swirling lines.

What is this thing? Why am I wearing it?

The black spots are multiplying, and it’s hard to focus. For some reason my tongue feels numb, and my legs are heavy, slow. I’ll just sit down for a minute, catch my breath, and then I’ll …

In the distance, I hear a thud, and my last thought is that I should have been more careful about where I put my head.