Complete Works of Emile Zola (210 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

But the one-eyed man was growing impatient; giving a push to Mourgue, who was lagging behind, he growled: “Get along, do; I don’t want to be here all night.”

Silvere stumbled. He looked at his feet. A fragment of a skull lay whitening in the grass. He thought he heard a murmur of voices filling the pathway. The dead were calling him, those long departed ones, whose warm breath had so strangely perturbed him and his sweetheart during the sultry July evenings. He recognised their low whispers. They were rejoicing, they were telling him to come, and promising to restore Miette to him beneath the earth, in some retreat which would prove still more sequestered than this old trysting-place. The cemetery, whose oppressive odours and dark vegetation had breathed eager desire into the children’s hearts, while alluringly spreading out its couches of rank grass, without succeeding however in throwing them into one another’s arms, now longed to imbibe Silvere’s warm blood. For two summers past it had been expecting the young lovers.

“Is it here?” asked the one-eyed man.

Silvere looked in front of him. He had reached the end of the path. His eyes fell on the tombstone, and he started. Miette was right, that stone was for her.

“Here lieth . . . Marie . . . died . . . “

She was dead, that slab had fallen over her. His strength failing him, he leant against the frozen stone. How warm it had been when they sat in that nook, chatting for many a long evening! She had always come that way, and the pressure of her foot, as she alighted from the wall, had worn away the stone’s surface in one corner. The mark seemed instinct with something of her lissom figure. And to Silvere it appeared as if some fatalism attached to all these objects — as if the stone were there precisely in order that he might come to die beside it, there where he had loved.

The one-eyed man cocked his pistols.

Death! death! the thought fascinated Silvere. It was to this spot, then, that they had led him, by the long white road which descends from Sainte-Roure to Plassans. If he had known it, he would have hastened on yet more quickly in order to die on that stone, at the end of the narrow path, in the atmosphere where he could still detect the scent of Miette’s breath! Never had he hoped for such consolation in his grief. Heaven was merciful. He waited, a vague smile playing on is face.

Mourgue, meantime, had caught sight of the pistols. Hitherto he had allowed himself to be dragged along stupidly. But fear now overcame him, and he repeated, in a tone of despair: “I come from Poujols — I come from Poujols!”

Then he threw himself on the ground, rolling at the gendarme’s feet, breaking out into prayers for mercy, and imagining that he was being mistaken for some one else.

“What does it matter to me that you come from Poujols?” Rengade muttered.

And as the wretched man, shivering and crying with terror, and quite unable to understand why he was going to die, held out his trembling hands — his deformed, hard, labourer’s hands — exclaiming in his patois that he had done nothing and ought to be pardoned, the one-eyed man grew quite exasperated at being unable to put the pistol to his temple, owing to his constant movements.

“Will you hold your tongue?” he shouted.

Thereupon Mourgue, mad with fright and unwilling to die, began to howl like a beast — like a pig that is being slaughtered.

“Hold your tongue, you scoundrel!” the gendarme repeated.

And he blew his brains out. The peasant fell with a thud. His body rolled to the foot of a timber-stack, where it remained doubled up. The violence of the shock had severed the rope which fastened him to his companion. Silvere fell on his knees before the tombstone.

It was to make his vengeance the more terrible that Rengade had killed Mourgue first. He played with his second pistol, raising it slowly in order to relish Silvere’s agony. But the latter looked at him quietly. Then again the sight of this man, with the one fierce, scorching eye, made him feel uneasy. He averted his glance, fearing that he might die cowardly if he continued to look at that feverishly quivering gendarme, with blood-stained bandage and bleeding moustache. However, as he raised his eyes to avoid him, he perceived Justin’s head just above the wall, at the very spot where Miette had been wont to leap over.

Justin had been at the Porte de Rome, among the crowd, when the gendarme had led the prisoners away. He had set off as fast as he could by way of the Jas-Meiffren, in his eagerness to witness the execution. The thought that he alone, of all the Faubourg scamps, would view the tragedy at his ease, as from a balcony, made him run so quickly that he twice fell down. And in spite of his wild chase, he arrived too late to witness the first shot. He climbed the mulberry tree in despair; but he smiled when he saw that Silvere still remained. The soldiers had informed him of his cousin’s death, and now the murder of the wheelwright brought his happiness to a climax. He awaited the shot with that delight which the sufferings of others always afforded him — a delight increased tenfold by the horror of the scene, and a feeling of exquisite fear.

Silvere, on recognising that vile scamp’s head all by itself above the wall — that pale grinning face, with hair standing on end — experienced a feeling of fierce rage, a sudden desire to live. It was the last revolt of his blood — a momentary mutiny. He again sank down on his knees, gazing straight before him. A last vision passed before his eyes in the melancholy twilight. At the end of the path, at the entrance of the Impasse Saint-Mittre, he fancied he could see aunt Dide standing erect, white and rigid like the statue of a saint, while she witnessed his agony from a distance.

At that moment he felt the cold pistol on his temple. There was a smile on Justin’s pale face. Closing his eyes, Silvere heard the long-departed dead wildly summoning him. In the darkness, he now saw nothing save Miette, wrapped in the banner, under the trees, with her eyes turned towards heaven. Then the one-eyed man fired, and all was over; the lad’s skull burst open like a ripe pomegranate; his face fell upon the stone, with his lips pressed to the spot which Miette’s feet had worn — that warm spot which still retained a trace of his dead love.

And in the evening at dessert, at the Rougons’ abode, bursts of laughter arose with the fumes from the table, which was still warm with the remains of the dinner. At last the Rougons were nibbling at the pleasures of the wealthy! Their appetites, sharpened by thirty years of restrained desire, now fell to with wolfish teeth. These fierce, insatiate wild beasts, scarcely entering upon indulgence, exulted at the birth of the Empire — the dawn of the Rush for the Spoils. The Coup d’Etat, which retrieved the fortune of the Bonapartes, also laid the foundation for that of the Rougons.

Pierre stood up, held out his glass, and exclaimed: “I drink to Prince Louis — to the Emperor!”

The gentlemen, who had drowned their jealousies in champagne, rose in a body and clinked glasses with deafening shouts. It was a fine spectacle. The bourgeois of Plassans, Roudier, Granoux, Vuillet, and all the others, wept and embraced each other over the corpse of the Republic, which as yet was scarcely cold. But a splendid idea occurred to Sicardot. He took from Felicite’s hair a pink satin bow, which she had placed over her right ear in honour of the occasion, cut off a strip of the satin with his dessert knife, and then solemnly fastened it to Rougon’s button-hole. The latter feigned modesty, and pretended to resist. But his face beamed with joy, as he murmured: “No, I beg you, it is too soon. We must wait until the decree is published.”

“Zounds!” Sicardot exclaimed, “will you please keep that! It’s an old soldier of Napoleon who decorates you!”

The whole company burst into applause. Felicite almost swooned with delight. Silent Granoux jumped up on a chair in his enthusiasm, waving his napkin and making a speech which was lost amid the uproar. The yellow drawing-room was wild with triumph.

But the strip of pink satin fastened to Pierre’s button-hole was not the only red spot in that triumph of the Rougons. A shoe, with a blood-stained heel, still lay forgotten under the bedstead in the adjoining room. The taper burning at Monsieur Peirotte’s bedside, over the way, gleamed too with the lurid redness of a gaping wound amidst the dark night. And yonder, far away, in the depths of the Aire Saint-Mittre, a pool of blood was congealing upon a tombstone.

THE KILL

Translated by Alexander Texeira de Mattos

The second novel of

Les Rougon-Macquart

,

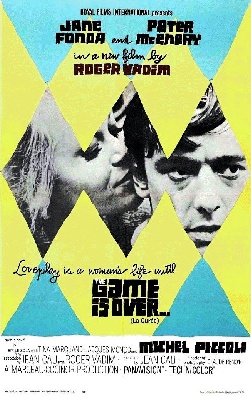

La Curée

concerns property speculation and the lives of the extremely wealthy Nouveau riche of the Second French Empire, in mid nineteenth-century Paris. The title of the novel refers to the portion of the game thrown to the dogs after a hunt, hinting at the sinister nature of the work. Unlike the previous novel in the cycle,

La Curée

is a much smaller canvas on which Zola works upon, studying three personalities in detail. The protagonist is Aristide Rougon, later renamed “Saccard”, the youngest son of the ruthless and calculating peasant Pierre Rougon and the bourgeois Félicité, the two Bonapartistes in the first novel that were consumed by a desire for wealth.

La Curée

also introduces Aristide’s young second wife Renée - his first dying shortly after their move from Plassans to Paris – and the third main character of the novel is Maxime, Saccard’s depraved and foppish son, from his first marriage.

The novel opens with a description of decadent splendour, with Renée and Maxime lazing in a luxurious carriage, idly leaving a Parisian park. From the start it is apparent they lead indolent lives tainted by their incredible wealth. The following section steps back in time, depicting how Aristide (Saccard) rose to power after leaving Plassans to join his brother Eugene Rougon, who has achieved a place in the new government, following his machinations in the

La Fortune des Rougon

. However, it is the incestful relationship of Maxime and Renée that dominates the second half of the novel, further examining the degenerate nature of the Rougon family’s evolution.

The 1966 film adaptation of the novel

CONTENTS

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER I

On the drive home, the calash could make but little way against the obstruction of carriages returning by the edge of the lake. At one moment the block became such that it was even necessary to pull up.

The sun was setting in a pale gray October sky, streaked on the horizon with thin clouds. One last ray, falling from the distant shrubberies of the cascade, pierced the roadway, and flooded the long array of stationary carriages with pale red light. The golden glints, the bright flashes thrown by the wheels, seemed to have settled along the straw-coloured edges of the calash, while the dark-blue panels reflected bits of the surrounding landscape. And higher up, full in the red light that lit them up from behind, and gave effulgence to the brass buttons of their capes half-folded across the back of the box, sat the coachman and footman, in their dark-blue liveries, their drab breeches, and their yellow-and-black striped waist-coats, erect, solemn and patient, after the manner of well-bred servants who are in no way put out by a block of carriages. Their hats, adorned with black cockades, looked very dignified. The horses alone, a pair of splendid bays, snorted with impatience.

“Look,” said Maxime, “Laure d’Aurigny, over there, in that brougham…. Do look, Renée.”

Renée raised herself slightly, and blinked her eyes with the exquisite grimace caused by the shortness of her sight.

“I thought she had vanished from the scene,” said Renée…. “She has changed the colour of her hair, has she not?”

“Yes,” replied Maxime, laughing; “her new lover hates red.”

Awakened from the melancholy dream that for an hour had kept her silent, stretched out in the back seat of the carriage as in an invalid’s long-chair, Renée leaned forward and looked, resting her hand on the low door of the calash. Over a gown consisting of a mauve silk polonaise and tunic, trimmed with wide plaited flounces, she wore a little coat of white cloth with mauve velvet lapels, which gave her a look of great smartness. Her strange, pale, fawn-coloured hair, whose shade recalled the colour of good butter, was barely concealed by a tiny bonnet adorned with a cluster of Bengal roses. She continued to screw up her eyes with her look of an impertinent boy, her pure forehead furrowed by one long wrinkle, her upper lip protruding like a sulky child’s. Then, finding that she could not see, she took her eye-glass, a man’s double eye-glass framed in tortoise-shell, and, holding it in her hand without placing it on her nose, at her ease examined the fat Laure d’Aurigny, with an air of absolute calmness.