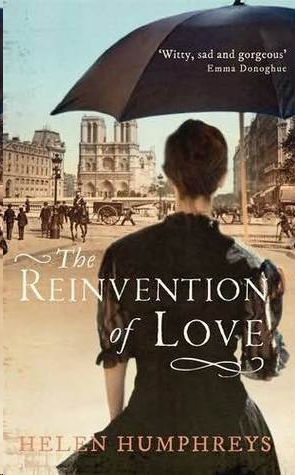

The Reinvention of Love

Helen Humphreys

is a novelist and poet. She was born in

the UK, and now lives in Kingston, Ontario. Humphreys’ first

novel,

Leaving Earth

, was a New York Times Notable Book in

1998 and won the City of Toronto Book Award. Her other

novels include

Afterimage

,

The Lost Garden

, and

Coventry

.

THE REINVENTION OF LOVE

Helen Humphreys

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the

British Library on request

The right of Helen Humphreys to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2011 Helen Humphreys

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in Canada in 2011 by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

First published in the UK in 2011 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

website:

www.serpentstail.com

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 84668 798 3

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 84668 833 1

eISBN: 978 1 84765 760 2

Designed and typeset by [email protected]

Printed by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my brother, Martin

“Le vrai, le vrai seul”

Sainte-Beuve

PARIS, 1830s

CHARLES

IT SEEMS I AM TO DIE AGAIN.

He slapped my face. I called him a “glorious inferior”. (Not in that order.) And here we are, in this rainy wood in the middle of the working week, trying to kill each other.

Let me explain.

I want to tell you everything.

The board meeting was long and dreary. I was tired. When the senior editor asked me to shorten my article, I objected. I am only a junior writer at the newspaper, but I am much more intelligent than anyone else there, and sometimes I just can’t pretend otherwise. It was careless of me to insult Monsieur Dubois because I know the possible consequences of such an action. And I was not disappointed. He practically sprang across the table to strike my face. His challenge could be heard by people walking outside on the crowded boulevard.

Antoine is my reluctant second. He is out of the cab already, the wooden case with the duelling pistols tucked securely under one arm. “Come on,” he says. “They’re waiting.” And, through the open door of the cab I can see Pierre Dubois and his second, the print runner, Bernard, standing under a straggly stand of trees at the edge of the wood.

“I haven’t even had my breakfast,” I say, struggling to open my umbrella before I step down onto the soggy ground.

“Get out,” says Antoine, unsympathetically, and I feel like challenging

him

to a duel for his insolence. I snap open my umbrella.

“Please be serious,” he says.

“What?”

“That.” He gestures towards the green umbrella with the yellow handle. I had thought it very dashing when I purchased it from a Paris shop last week. But I can see that here, out in nature, it looks a bit ridiculous.

“Lower it,” he says.

“I will not. I don’t mind being killed, but I refuse to get wet.”

We march off moodily into the wood.

Pierre Dubois also appears disheartened by my umbrella. It seems to make him feel sad for me, and perhaps he has second thoughts about shooting such a pitiful creature.

“You can offer me a profound apology,” he says, “and we can forget all about this.”

We are writers. We are meant to brandish pens, not pistols. I regret my insult. Pierre obviously regrets his challenge. I could apologize and we could share a cab back to the city and resume the business of making a newspaper.

But words are not easy to set aside. They make a shape in the mouth, a shape in the air. When something is said, it exists, and it is not easily persuaded again into silence. The truth is that I

do

think Pierre Dubois is my inferior. The truth is that I annoy him beyond reason and he would like to fire me, but he can’t because the readers are so fond of my reviews.

“I take nothing back,” I say.

“You are a fool,” says Pierre.

“You are a bigger fool.”

Now we can’t wait to shoot each other. Antoine opens the case and loads the pistols. Bernard has disappeared behind a tree to relieve himself.

The gun is heavy and smells of scorch and earth. I clutch it to my breast and pace off into the trees, counting the twenty strides under my breath, pausing only once when my umbrella snags in the branches overhead.

Pierre has challenged me, so I am to shoot first. I stop. I turn. I raise my hand with the pistol in it and sight down my arm. Pierre is partially obscured by scrub. The rain erases his outline. I squint, then I pull the trigger. The gun kicks and smokes, and for a moment I can’t see anything. Someone yells and I’m afraid I have hit Pierre, but when the smoke clears he remains as he was, standing in the rain in the middle of some bushes.

Now it is Pierre’s turn.

The bright green umbrella will help guide the lead ball to its target, but I refuse to sheath it because I had insisted on bringing it. But what if my stubbornness causes my death? It occurs to me, for the first time, that I am perhaps too wilful for my own good, that I am not helped by my character, that it potentially causes me great harm, and that I should probably fight hard against it.

“You will get another shot,” says Antoine, appearing suddenly at my side. “Give me the pistol and I’ll reload for you.”

I pass it to him, and turn so that I can present the full fleshly target of my body to Pierre Dubois.

It is then that I think of Adèle, and how, if I die, she will weep and despair and be impressed by my courage. So, I had better summon some courage. I take a deep breath and hold it, close my eyes, and brace myself for the sting and the first bitter taste of darkness.

HE IS MY NEIGHBOUR.

We live two doors apart on Notre-Dame-des-Champs. He is also my dear friend. I am also in love with his wife.

Of Victor’s poetry I can say that nothing is better. Of his plays, nothing is worse. It is prudent of him, perhaps, to have recently become a novelist. But whatever he does he is wildly successful, driven by an appetite for glory that I envy and admire. I like to think that my glowing reviews of his poetry have helped to make him so famous. Certainly our friendship has blossomed because of my praise. It has also inspired my own writing and I have dedicated the first volume of my poems to Victor. Friendship is a consolation to me. I believe in its properties as some believe in religion.

But it doesn’t seem to have helped my book sales.

Have I mentioned already that I am in love with Victor’s wife, Adèle? To say that this complicates the friendship for me is an understatement. But for Victor, who knows nothing of my passion for Adèle, our friendship remains joyful and uncomplicated.

The Hugos have four children, the last, little Adèle, my goddaughter, was born just a few months ago. Their house is noisy and crowded, alive with laughter and schemes. I delight in its tumult after the calm seas of my own empty domicile.

Tonight, after my rather invigorating day in the countryside duelling with Monsieur Dubois, I enter to find Victor and Adèle in the kitchen with two men. There is a jug of wine on

the table. The men are drinking and pacing. Adèle sits in a chair with a large sheet of paper spread out on her lap. Several of the children run through the kitchen at intervals, chasing each other with a butterfly net and shrieking like birds at the zoo.

I am so often at the Hugos’ house that it has long ceased to be necessary for me to knock at the door and wait to be admitted. I just walk in.

“Charles,” says Victor, when he sees me standing in the kitchen doorway. “We are plotting. Come and help us.” He claps me on the back and passes his own glass of wine to me. “I think you know Theo and Luc.”

The young men who hang on the genius of Victor Hugo look indistinguishable to me. Theo could be Luc could be Henri could be Pascal. They are interchangeable, these admirers, and the great poet treats them with benevolence, but he uses them like servants.

I nod at the men, who glance my way briefly and then return their rapt attention to Victor.

“Here,” says Adèle, patting the chair beside hers. “Come and join me.” She looks up with her beautiful brown eyes and just the suggestion of a smile on her lips. I sit down. Our heads are a whisper apart. She has her hair up tonight. Often she does this so hastily that the twists of dark hair look like a nest of glossy sausages sitting atop of her perfectly shaped head.

“What are you doing?”

“Marching into battle,” says Victor, fetching a fresh glass and pouring himself some more wine. “Slaying the enemy.”

I look at the piece of paper on Adèle’s lap. It’s a seating map for the Comédie-Française.

“The anti-romantics don’t like

Hernani

,” she explains. “There are hecklers every night.”

“Ignorants,” shouts Victor. The children screech through the kitchen, waving the butterfly net like a gauzy flag.

Hernani

is the latest of Victor’s wretched plays. This time, the

melodrama is about two lovers who poison each other. The irony is not lost on me.

“We’re planting supporters. Here.” Adèle moves a finger across the drawing of the theatre balcony. “And here.” She moves her finger down to the dress circle and her arm gently grazes mine. I feel her touch all through my body. The jolt is as sharp as being shot.

“Everyone you can think of must be persuaded to come,” says Victor. “We must outnumber the enemy.”

“Is it the same hecklers every night then?” I ask.

“We think so.” Adèle pulls the seating diagram across her lap so that she can move her leg and press it against mine.