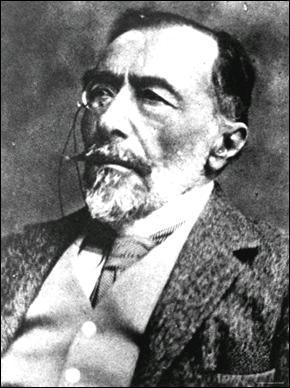

Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) (477 page)

Read Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) Online

Authors: JOSEPH CONRAD

Her eyelids fluttered. She looked drowsily about, serene, as if fatigued only by the exertions of her tremendous victory, capturing the very sting of death in the service of love. But her eyes became very wide awake when they caught sight of Ricardo’s dagger, the spoil of vanquished death, which Davidson was still holding, unconsciously.

“Give it to me,” she said. “It’s mine.”

Davidson put the symbol of her victory into her feeble hands extended to him with the innocent gesture of a child reaching eagerly for a toy.

“For you,” she gasped, turning her eyes to Heyst. “Kill nobody.”

“No,” said Heyst, taking the dagger and laying it gently on her breast, while her hands fell powerless by her side.

The faint smile on her deep-cut lips waned, and her head sank deep into the pillow, taking on the majestic pallor and immobility of marble. But over the muscles, which seemed set in their transfigured beauty for ever, passed a slight and awful tremor. With an amazing strength she asked loudly:

“What’s the matter with me?”

“You have been shot, dear Lena,” Heyst said in a steady voice, while Davidson, at the question, turned away and leaned his forehead against the post of the foot of the bed.

“Shot? I did think, too, that something had struck me.”

Over Samburan the thunder had ceased to growl at last, and the world of material forms shuddered no more under the emerging stars. The spirit of the girl which was passing away from under them clung to her triumph convinced of the reality of her victory over death.

“No more,” she muttered. “There will be no more! Oh, my beloved,” she cried weakly, “I’ve saved you! Why don’t you take me into your arms and carry me out of this lonely place?”

Heyst bent low over her, cursing his fastidious soul, which even at that moment kept the true cry of love from his lips in its infernal mistrust of all life. He dared not touch her and she had no longer the strength to throw her arms about his neck.

“Who else could have done this for you?” she whispered gloriously.

“No one in the world,” he answered her in a murmur of unconcealed despair.

She tried to raise herself, but all she could do was to lift her head a little from the pillow. With a terrible and gentle movement, Heyst hastened to slip his arm under her neck. She felt relieved at once of an intolerable weight, and was content to surrender to him the infinite weariness of her tremendous achievement. Exulting, she saw herself extended on the bed, in a black dress, and profoundly at peace, while, stooping over her with a kindly, playful smile, he was ready to lift her up in his firm arms and take her into the sanctuary of his innermost heart — for ever! The flush of rapture flooding her whole being broke out in a smile of innocent, girlish happiness; and with that divine radiance on her lips she breathed her last — triumphant, seeking for his glance in the shades of death.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

“Yes, Excellency,” said Davidson in his placid voice; “there are more dead in this affair — more white people, I mean — than have been killed in many of the battles in the last Achin war.”

Davidson was talking with an Excellency, because what was alluded to in conversation as “the mystery of Samburan” had caused such a sensation in the Archipelago that even those in the highest spheres were anxious to hear something at first hand. Davidson had been summoned to an audience. It was a high official on his tour.

“You knew the late Baron Heyst well?”

“The truth is that nobody out here can boast of having known him well,” said Davidson. “He was a queer chap. I doubt if he himself knew how queer he was. But everybody was aware that I was keeping my eye on him in a friendly way. And that’s how I got the warning which made me turn round in my tracks. In the middle of my trip and steam back to Samburan, where, I am grieved to say, I arrived too late.”

Without enlarging very much, Davidson explained to the attentive Excellency how a woman, the wife of a certain hotel-keeper named Schomberg, had overheard two card-sharping rascals making inquiries from her husband as to the exact position of the island. She caught only a few words referring to the neighbouring volcano, but there were enough to arouse her suspicions — ”which,” went on Davidson, “she imparted to me, your Excellency. They were only too well founded!”

“That was very clever of her,” remarked the great man.

“She’s much cleverer than people have any conception of,” said Davidson.

But he refrained from disclosing to the Excellency the real cause which had sharpened Mrs. Schomberg’s wits. The poor woman was in mortal terror of the girl being brought back within reach of her infatuated Wilhelm. Davidson only said that her agitation had impressed him; but he confessed that while going back, he began to have his doubts as to there being anything in it.

“I steamed into one of those silly thunderstorms that hang about the volcano, and had some trouble in making the island,” narrated Davidson. “I had to grope my way dead slow into Diamond Bay. I don’t suppose that anybody, even if looking out for me, could have heard me let go the anchor.”

He admitted that he ought to have gone ashore at once; but everything was perfectly dark and absolutely quiet. He felt ashamed of his impulsiveness. What a fool he would have looked, waking up a man in the middle of the night just to ask him if he was all right! And then the girl being there, he feared that Heyst would look upon his visit as an unwarrantable intrusion.

The first intimation he had of there being anything wrong was a big white boat, adrift, with the dead body of a very hairy man inside, bumping against the bows of his steamer. Then indeed he lost no time in going ashore — alone, of course, from motives of delicacy.

“I arrived in time to see that poor girl die, as I have told your Excellency,” pursued Davidson. “I won’t tell you what a time I had with him afterwards. He talked to me. His father seems to have been a crank, and to have upset his head when he was young. He was a queer chap. Practically the last words he said to me, as we came out on the veranda, were:

“‘Ah, Davidson, woe to the man whose heart has not learned while young to hope, to love — and to put its trust in life!’

“As we stood there, just before I left him, for he said he wanted to be alone with his dead for a time, we heard a snarly sort of voice near the bushes by the shore calling out:

“‘Is that you, governor?’

“‘Yes, it’s me.’

“‘Jeeminy! I thought the beggar had done for you. He has started prancing and nearly had me. I have been dodging around, looking for you ever since.’

“‘Well, here I am,’ suddenly screamed the other voice, and then a shot rang out.

“‘This time he has not missed him,’ Heyst said to me bitterly, and went back into the house.

“I returned on board as he had insisted I should do. I didn’t want to intrude on his grief. Later, about five in the morning, some of my calashes came running to me, yelling that there was a fire ashore. I landed at once, of course. The principal bungalow was blazing. The heat drove us back. The other two houses caught one after another like kindling-wood. There was no going beyond the shore end of the jetty till the afternoon.”

Davidson sighed placidly.

“I suppose you are certain that Baron Heyst is dead?”

“He is — ashes, your Excellency,” said Davidson, wheezing a little; “he and the girl together. I suppose he couldn’t stand his thoughts before her dead body — and fire purifies everything. That Chinaman of whom I told your Excellency helped me to investigate next day, when the embers got cooled a little. We found enough to be sure. He’s not a bad Chinaman. He told me that he had followed Heyst and the girl through the forest from pity, and partly out of curiosity. He watched the house till he saw Heyst go out, after dinner, and Ricardo come back alone. While he was dodging there, it occurred to him that he had better cast the boat adrift, for fear those scoundrels should come round by water and bombard the village from the sea with their revolvers and Winchesters. He judged that they were devils enough for anything. So he walked down the wharf quietly; and as he got into the boat, to cast her off, that hairy man who, it seems, was dozing in her, jumped up growling, and Wang shot him dead. Then he shoved the boat off as far as he could and went away.”

There was a pause. Presently Davidson went on, in his tranquil manner:

“Let Heaven look after what has been purified. The wind and rain will take care of the ashes. The carcass of that follower, secretary, or whatever the unclean ruffian called himself, I left where it lay, to swell and rot in the sun. His principal had shot him neatly through the head. Then, apparently, this Jones went down to the wharf to look for the boat and for the hairy man. I suppose he tumbled into the water by accident — or perhaps not by accident. The boat and the man were gone, and the scoundrel saw himself alone, his game clearly up, and fairly trapped. Who knows? The water’s very clear there, and I could see him huddled up on the bottom, between two piles, like a heap of bones in a blue silk bag, with only the head and the feet sticking out. Wang was very pleased when he discovered him. That made everything safe, he said, and he went at once over the hill to fetch his Alfuro woman back to the hut.”

Davidson took out his handkerchief to wipe the perspiration off his forehead.

“And then, your Excellency, I went away. There was nothing to be done there.”

“Clearly!” assented the Excellency.

Davidson, thoughtful, seemed to weigh the matter in his mind, and then murmured with placid sadness:

“Nothing!”

October 1912 — May 1914

THE SHADOW-LINE

A CONFESSION

“Worthy of my undying regard”

To Borys And All Others Who,

Like Himself, Have Crossed In Early Youth

The Shadow-Line Of Their Generation With Love

— D’autre fois, calme plat, grand miroir De mon desespoir. — BAUDELAIRE

CONTENTS

PART ONE

I

Only the young have such moments. I don’t mean the very young. No. The very young have, properly speaking, no moments. It is the privilege of early youth to live in advance of its days in all the beautiful continuity of hope which knows no pauses and no introspection.

One closes behind one the little gate of mere boyishness — and enters an enchanted garden. Its very shades glow with promise. Every turn of the path has its seduction. And it isn’t because it is an undiscovered country. One knows well enough that all mankind had streamed that way. It is the charm of universal experience from which one expects an uncommon or personal sensation — a bit of one’s own.

One goes on recognizing the landmarks of the predecessors, excited, amused, taking the hard luck and the good luck together — the kicks and the half-pence, as the saying is — the picturesque common lot that holds so many possibilities for the deserving or perhaps for the lucky. Yes. One goes on. And the time, too, goes on — till one perceives ahead a shadow-line warning one that the region of early youth, too, must be left behind.

This is the period of life in which such moments of which I have spoken are likely to come. What moments? Why, the moments of boredom, of weariness, of dissatisfaction. Rash moments. I mean moments when the still young are inclined to commit rash actions, such as getting married suddenly or else throwing up a job for no reason.

This is not a marriage story. It wasn’t so bad as that with me. My action, rash as it was, had more the character of divorce — almost of desertion. For no reason on which a sensible person could put a finger I threw up my job — chucked my berth — left the ship of which the worst that could be said was that she was a steamship and therefore, perhaps, not entitled to that blind loyalty which. . . . However, it’s no use trying to put a gloss on what even at the time I myself half suspected to be a caprice.