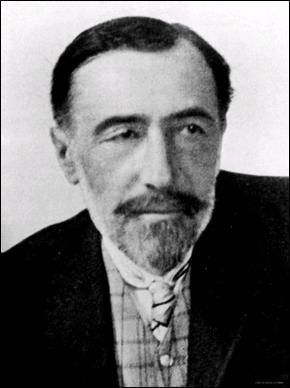

Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) (582 page)

Read Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) Online

Authors: JOSEPH CONRAD

“I wonder which of us two was mad,” he said.

“I wonder you can bear to look at me,” she murmured. Then Lingard spoke again.

“I had to see you once more.”

“That abominable Jorgenson,” she whispered to herself.

“No, no, he gave me my chance — before he gave me up.”

Mrs. Travers disengaged her arm and Lingard stopped, too, facing her in a long silence.

“I could not refuse to meet you,” said Mrs. Travers at last. “I could not refuse you anything. You have all the right on your side and I don’t care what you do or say. But I wonder at my own courage when I think of the confession I have to make.” She advanced, laid her hand on Lingard’s shoulder and spoke earnestly. “I shuddered at the thought of meeting you again. And now you must listen to my confession.”

“Don’t say a word,” said Lingard in an untroubled voice and never taking his eyes from her face. “I know already.”

“You can’t,” she cried. Her hand slipped off his shoulder. “Then why don’t you throw me into the sea?” she asked, passionately. “Am I to live on hating myself?”

“You mustn’t!” he said with an accent of fear. “Haven’t you understood long ago that if you had given me that ring it would have been just the same?”

“Am I to believe this? No, no! You are too generous to a mere sham. You are the most magnanimous of men but you are throwing it away on me. Do you think it is remorse that I feel? No. If it is anything it is despair. But you must have known that — and yet you wanted to look at me again.”

“I told you I never had a chance before,” said Lingard in an unmoved voice. “It was only after I heard they gave you the ring that I felt the hold you have got on me. How could I tell before? What has hate or love to do with you and me? Hate. Love. What can touch you? For me you stand above death itself; for I see now that as long as I live you will never die.”

They confronted each other at the southern edge of the sands as if afloat on the open sea. The central ridge heaped up by the winds masked from them the very mastheads of the two ships and the growing brightness of the light only augmented the sense of their invincible solitude in the awful serenity of the world. Mrs. Travers suddenly put her arm across her eyes and averted her face.

Then he added:

“That’s all.”

Mrs. Travers let fall her arm and began to retrace her steps, unsupported and alone. Lingard followed her on the edge of the sand uncovered by the ebbing tide. A belt of orange light appeared in the cold sky above the black forest of the Shore of Refuge and faded quickly to gold that melted soon into a blinding and colourless glare. It was not till after she had passed Jaffir’s grave that Mrs. Travers stole a backward glance and discovered that she was alone. Lingard had left her to herself. She saw him sitting near the mound of sand, his back bowed, his hands clasping his knees, as if he had obeyed the invincible call of his great visions haunting the grave of the faithful messenger. Shading her eyes with her hand Mrs. Travers watched the immobility of that man of infinite illusions. He never moved, he never raised his head. It was all over. He was done with her. She waited a little longer and then went slowly on her way.

Shaw, now acting second mate of the yacht, came off with another hand in a little boat to take Mrs. Travers on board. He stared at her like an offended owl. How the lady could suddenly appear at sunrise waving her handkerchief from the sandbank he could not understand. For, even if she had managed to row herself off secretly in the dark, she could not have sent the empty boat back to the yacht. It was to Shaw a sort of improper miracle.

D’Alcacer hurried to the top of the side ladder and as they met on deck Mrs. Travers astonished him by saying in a strangely provoking tone:

“You were right. I have come back.” Then with a little laugh which impressed d’Alcacer painfully she added with a nod downward, “and Martin, too, was perfectly right. It was absolutely unimportant.”

She walked on straight to the taffrail and d’Alcacer followed her aft, alarmed at her white face, at her brusque movements, at the nervous way in which she was fumbling at her throat. He waited discreetly till she turned round and thrust out toward him her open palm on which he saw a thick gold ring set with a large green stone.

“Look at this, Mr. d’Alcacer. This is the thing which I asked you whether I should give up or conceal — the symbol of the last hour — the call of the supreme minute. And he said it would have made no difference! He is the most magnanimous of men and the uttermost farthing has been paid. He has done with me. The most magnanimous . . . but there is a grave on the sands by which I left him sitting with no glance to spare for me. His last glance on earth! I am left with this thing. Absolutely unimportant. A dead talisman.” With a nervous jerk she flung the ring overboard, then with a hurried entreaty to d’Alcacer, “Stay here a moment. Don’t let anybody come near us,” she burst into tears and turned her back on him.

Lingard returned on board his brig and in the early afternoon the Lightning got under way, running past the schooner to give her a lead through the maze of Shoals. Lingard was on deck but never looked once at the following vessel. Directly both ships were in clear water he went below saying to Carter: “You know what to do.”

“Yes, sir,” said Carter.

Shortly after his Captain had disappeared from the deck Carter laid the main topsail to the mast. The Lightning lost her way while the schooner with all her light kites abroad passed close under her stern holding on her course. Mrs. Travers stood aft very rigid, gripping the rail with both hands. The brim of her white hat was blown upward on one side and her yachting skirt stirred in the breeze. By her side d’Alcacer waved his hand courteously. Carter raised his cap to them.

During the afternoon he paced the poop with measured steps, with a pair of binoculars in his hand. At last he laid the glasses down, glanced at the compass-card and walked to the cabin skylight which was open.

“Just lost her, sir,” he said. All was still down there. He raised his voice a little:

“You told me to let you know directly I lost sight of the yacht.”

The sound of a stifled groan reached the attentive Carter and a weary voice said, “All right, I am coming.”

When Lingard stepped out on the poop of the Lightning the open water had turned purple already in the evening light, while to the east the Shallows made a steely glitter all along the sombre line of the shore. Lingard, with folded arms, looked over the sea. Carter approached him and spoke quietly.

“The tide has turned and the night is coming on. Hadn’t we better get away from these Shoals, sir?”

Lingard did not stir.

“Yes, the night is coming on. You may fill the main topsail, Mr. Carter,” he said and he relapsed into silence with his eyes fixed in the southern board where the shadows were creeping stealthily toward the setting sun. Presently Carter stood at his elbow again.

“The brig is beginning to forge ahead, sir,” he said in a warning tone.

Lingard came out of his absorption with a deep tremor of his powerful frame like the shudder of an uprooted tree.

“How was the yacht heading when you lost sight of her?” he asked.

“South as near as possible,” answered Carter. “Will you give me a course to steer for the night, sir?”

Lingard’s lips trembled before he spoke but his voice was calm.

“Steer north,” he said.

THE NATURE OF A CRIME

JOSEPH CONRAD AND FORD MADOX HUEFFER

CONTENTS

PREFACE BY JOSEPH CONRAD

FOR years my consciousness of this small piece of collaboration has been very vague, almost impalpable, like the fleeting visits from a ghost. If I ever thought of it, and I must confess that I can hardly remember ever doing it on purpose till it was brought definitely to my notice by my collaborator, I always regarded it as something in the nature of a fragment. I was surprised and even shocked to discover that it was rounded. But I need not have been. Rounded as it is in form, using the word form in its simplest sense — printed form — it remains yet a fragment from its very nature and also from necessity. It could never have become anything else. And even as a fragment it is but a fragment of something that might have been — of a mere intention.

But as it stands what impresses me most is the amount this fragment contains of the crudely materialistic atmosphere of the time of its origin, the time when the English Review was founded. It emerges from the depth of a past as distant from us now as the square-skirted, long frock-coats in which unscrupulous, cultivated, high-minded jouisseurs like ours here attended to their strange business activities and cultivated the little blue flower of sentiment. No doubt our man was conceived for purposes of irony; but our conception of him, I fear, is too fantastic.

Yet the most fantastic thing of all, as it seems to me, is that we two, who had so often discussed soberly the limits and the methods of literary composition, should have believed, for a moment, that a piece of work in the nature of an analytical confession (produced in articulo mortis as it were) could have been developed and achieved in collaboration !

What optimism ! But it did not last long. I seem to remember a moment when I burst into earnest entreaties that all those people should be thrown overboard without much ado. This, I believe, is the real nature of the crime. Overboard. The neatness and dispatch with which it is done in Chapter VIII were wholly the act of my collaborator’s good nature in the face of my panic.

After signing these few prefatory words, I will pass the pen to him in the hope that he may be moved to contradict me on every point of fact, impression and appreciation. I said “ the hope.” Yes. Eager hope. For it would be delightful to catch the echo of the desperate, earnest, eloquent and funny quarrels which enlivened those old days. The pity of it that there comes a time when all the fun of one’s life must be looked for in the past !

J. C.

June 1924

PREFACE BY FORD MADOX HUEFFER

No, I find nothing to contradict, for, the existence of this story having been recalled to my mind by a friend, the details of its birth and its attendant circumstances remain for me completely forgotten, a dark, blind spot on the brain. I cannot remember the houses in which the writing took place, the view from the windows, the pen, the table cloth. At a given point in my life I forgot, literally, all the books I had ever written; but, if nowadays I reread one of them, though I possess next to none and have reread few, nearly all the phrases come back startlingly to my memory, and I see glimpses of Kent, of Sussex, of Carcassonne — of New York, even; and fragments of furniture, mirrors, who knows what? So that, if I didn’t happen to retain, almost by a miracle, for me, of retention, the marked up copy of Romance from which was made the analysis lately published in a certain periodical, I am certain that I could have identified the phrases exactly as they stand. Looking at the book now I can hear our voices as we read one passage or another aloud for purposes of correction. Moreover, I could say: This passage was written in Kent and hammered over in Sussex; this, written in Sussex and worked on in Kent; or this again was written in the downstairs cafe, and hammered in the sitting-room on the first-floor of an hotel that faces the sea on the Belgian coast.

But of the Nature of a Crime no phrase at all suggests either the tones of a voice or the colour of a day. When an old friend, last year, on a Parisian Boulevard, said: “ Isn’t there a story by yourself and Collaborator buried in the So and So?” I repudiated the idea with a great deal of heat. Eventually I had to admit the, as it were, dead fact. And. having admitted that to myself, and my Collaborator having corroborated it, I was at once possessed by a sort of morbid craving to get the story republished in a definite and acknowledged form. One may care infinitely little for the fate of one’s work, and yet be almost hypochondriacally anxious as to the form its publication shall take — if the publication is likely to occur posthumously. I became at once dreadfully afraid that some philologist of that Posterity for which one writes might, in the course of his hyena occupation, disinter these poor bones, and, attributing sentence one to writer A and sentence two to B. maul at least one of our memories. With the nature of those crimes one is only too well acquainted. Besides, though one may never read comments one desires to get them over. It is, indeed, agreeable to hear a storm rage in the distance, and rumble eventually away.