Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) (851 page)

Read Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) Online

Authors: JOSEPH CONRAD

She was a big, high-class cargo-steamer of a type that is to be met on the sea no more — black hull, with low, white superstructures, powerfully rigged with three masts and a lot of yards on the fore; two hands at her enormous wheel — steam steering-gear was not a matter of course in these days — and with them on the bridge three others, bulky in thick blue jackets, ruddy-faced, muffled up, with peak caps — I suppose all her officers. There are ships I have met more than once and known well by sight whose names I have forgotten; but the name of that ship seen once so many years ago in the clear flush of a cold, pale sunrise I have not forgotten. How could I — the first English ship on whose side I ever laid my hand! The name — I read it letter by letter on the bow — was James Westoll. Not very romantic, you will say. The name of a very considerable, well-known, and universally respected North country ship-owner, I believe. James Westoll! What better name could an honourable hard-working ship have? To me the very grouping of the letters is alive with the romantic feeling of her reality as I saw her floating motionless and borrowing an ideal grace from the austere purity of the light.

We were then very near her and, on a sudden impulse, I volunteered to pull bow in the dinghy which shoved off at once to put the pilot on board while our boat, fanned by the faint air which had attended us all through the night, went on gliding gently past the black, glistening length of the ship. A few strokes brought us alongside, and it was then that, for the very first time in my life, I heard myself addressed in English — the speech of my secret choice, of my future, of long friendships, of the deepest affections, of hours of toil and hours of ease, and of solitary hours, too, of books read, of thoughts pursued, of remembered emotions — of my very dreams! And if (after being thus fashioned by it in that part of me which cannot decay) I dare not claim it aloud as my own, then, at any rate, the speech of my children. Thus small events grow memorable by the passage of time. As to the quality of the address itself I cannot say it was very striking. Too short for eloquence and devoid of all charm of tone, it consisted precisely of the three words “Look out there!” growled out huskily above my head.

It proceeded from a big fat fellow (he had an obtrusive, hairy double chin) in a blue woollen shirt and roomy breeches pulled up very high, even to the level of his breastbone, by a pair of braces quite exposed to public view. As where he stood there was no bulwark, but only a rail and stanchions, I was able to take in at a glance the whole of his voluminous person from his feet to the high crown of his soft black hat, which sat like an absurd flanged cone on his big head. The grotesque and massive aspect of that deck hand (I suppose he was that — very likely the lamp-trimmer) surprised me very much. My course of reading, of dreaming, and longing for the sea had not prepared me for a sea brother of that sort. I never met again a figure in the least like his except in the illustrations to Mr. W. W. Jacobs’s most entertaining tales of barges and coasters; but the inspired talent of Mr. Jacobs for poking endless fun at poor, innocent sailors in a prose which, however extravagant in its felicitous invention, is always artistically adjusted to observed truth, was not yet. Perhaps Mr. Jacobs himself was not yet. I fancy that, at most, if he had made his nurse laugh it was about all he had achieved at that early date.

Therefore, I repeat, other disabilities apart, I could not have been prepared for the sight of that husky old porpoise. The object of his concise address was to call my attention to a rope which he incontinently flung down for me to catch. I caught it, though it was not really necessary, the ship having no way on her by that time. Then everything went on very swiftly. The dinghy came with a slight bump against the steamer’s side; the pilot, grabbing for the rope ladder, had scrambled half-way up before I knew that our task of boarding was done; the harsh, muffled clanging of the engine-room telegraph struck my ear through the iron plate; my companion in the dinghy was urging me to “shove off — push hard”; and when I bore against the smooth flank of the first English ship I ever touched in my life, I felt it already throbbing under my open palm.

Her head swung a little to the west, pointing toward the miniature lighthouse of the Jolliette breakwater, far away there, hardly distinguishable against the land. The dinghy danced a squashy, splashy jig in the wash of the wake; and, turning in my seat, I followed the James Westoll with my eyes. Before she had gone in a quarter of a mile she hoisted her flag, as the harbour regulations prescribe for arriving and departing ships. I saw it suddenly flicker and stream out on the flag staff. The Red Ensign! In the pellucid, colourless atmosphere bathing the drab and gray masses of that southern land, the livid islets, the sea of pale, glassy blue under the pale, glassy sky of that cold sunrise, it was, as far as the eye could reach, the only spot of ardent colour — flame-like, intense, and presently as minute as the tiny red spark the concentrated reflection of a great fire kindles in the clear heart of a globe of crystal. The Red Ensign — the symbolic, protecting, warm bit of bunting flung wide upon the seas, and destined for so many years to be the only roof over my head.

The Essays

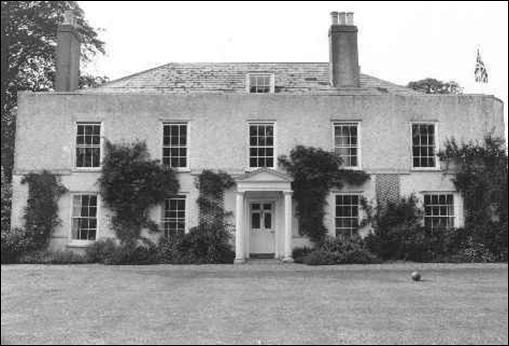

‘Oswalds’ in Bishopsbourne, near Canterbury, where Conrad moved to in 1918 and remained for the rest of his life

NOTES ON LIFE AND LETTERS

CONTENTS

HENRY JAMES — AN APPRECIATION — 1905

STEPHEN CRANE — A NOTE WITHOUT DATES — 1919

THE CENSOR OF PLAYS — AN APPRECIATION — 1907

A NOTE ON THE POLISH PROBLEM — 1916

SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE LOSS OF THE TITANIC — 1912

CERTAIN ASPECTS OF THE ADMIRABLE INQUIRY INTO THE LOSS OF THE TITANIC — 1912

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I don’t know whether I ought to offer an apology for this collection which has more to do with life than with letters. Its appeal is made to orderly minds. This, to be frank about it, is a process of tidying up, which, from the nature of things, cannot be regarded as premature. The fact is that I wanted to do it myself because of a feeling that had nothing to do with the considerations of worthiness or unworthiness of the small (but unbroken) pieces collected within the covers of this volume. Of course it may be said that I might have taken up a broom and used it without saying anything about it. That, certainly, is one way of tidying up.

But it would have been too much to have expected me to treat all this matter as removable rubbish. All those things had a place in my life. Whether any of them deserve to have been picked up and ranged on the shelf — this shelf — I cannot say, and, frankly, I have not allowed my mind to dwell on the question. I was afraid of thinking myself into a mood that would hurt my feelings; for those pieces of writing, whatever may be the comment on their display, appertain to the character of the man.

And so here they are, dusted, which was but a decent thing to do, but in no way polished, extending from the year ‘98 to the year ‘20, a thin array (for such a stretch of time) of really innocent attitudes: Conrad literary, Conrad political, Conrad reminiscent, Conrad controversial. Well, yes! A one-man show — or is it merely the show of one man?

The only thing that will not be found amongst those Figures and Things that have passed away, will be Conrad

en pantoufles

. It is a constitutional inability.

Schlafrock und pantoffeln

! Not that! Never! . . . I don’t know whether I dare boast like a certain South American general who used to say that no emergency of war or peace had ever found him “with his boots off”; but I may say that whenever the various periodicals mentioned in this book called on me to come out and blow the trumpet of personal opinions or strike the pensive lute that speaks of the past, I always tried to pull on my boots first. I didn’t want to do it, God knows! Their Editors, to whom I beg to offer my thanks here, made me perform mainly by kindness but partly by bribery. Well, yes! Bribery? What can you expect? I never pretended to be better than the people in the next street, or even in the same street.

This volume (including these embarrassed introductory remarks) is as near as I shall ever come to

dêshabillé

in public; and perhaps it will do something to help towards a better vision of the man, if it gives no more than a partial view of a piece of his back, a little dusty (after the process of tidying up), a little bowed, and receding from the world not because of weariness or misanthropy but for other reasons that cannot be helped: because the leaves fall, the water flows, the clock ticks with that horrid pitiless solemnity which you must have observed in the ticking of the hall clock at home. For reasons like that. Yes! It recedes. And this was the chance to afford one more view of it — even to my own eyes.

The section within this volume called Letters explains itself, though I do not pretend to say that it justifies its own existence. It claims nothing in its defence except the right of speech which I believe belongs to everybody outside a Trappist monastery. The part I have ventured, for shortness’ sake, to call Life, may perhaps justify itself by the emotional sincerity of the feelings to which the various papers included under that head owe their origin. And as they relate to events of which everyone has a date, they are in the nature of sign-posts pointing out the direction my thoughts were compelled to take at the various cross-roads. If anybody detects any sort of consistency in the choice, this will be only proof positive that wisdom had nothing to do with it. Whether right or wrong, instinct alone is invariable; a fact which only adds a deeper shade to its inherent mystery. The appearance of intellectuality these pieces may present at first sight is merely the result of the arrangement of words. The logic that may be found there is only the logic of the language. But I need not labour the point. There will be plenty of people sagacious enough to perceive the absence of all wisdom from these pages. But I believe sufficiently in human sympathies to imagine that very few will question their sincerity. Whatever delusions I may have suffered from I have had no delusions as to the nature of the facts commented on here. I may have misjudged their import: but that is the sort of error for which one may expect a certain amount of toleration.

The only paper of this collection which has never been published before is the Note on the Polish Problem. It was written at the request of a friend to be shown privately, and its “Protectorate” idea, sprung from a strong sense of the critical nature of the situation, was shaped by the actual circumstances of the time. The time was about a month before the entrance of Roumania into the war, and though, honestly, I had seen already the shadow of coming events I could not permit my misgivings to enter into and destroy the structure of my plan. I still believe that there was some sense in it. It may certainly be charged with the appearance of lack of faith and it lays itself open to the throwing of many stones; but my object was practical and I had to consider warily the preconceived notions of the people to whom it was implicitly addressed, and also their unjustifiable hopes. They were unjustifiable, but who was to tell them that? I mean who was wise enough and convincing enough to show them the inanity of their mental attitude? The whole atmosphere was poisoned with visions that were not so much false as simply impossible. They were also the result of vague and unconfessed fears, and that made their strength. For myself, with a very definite dread in my heart, I was careful not to allude to their character because I did not want the Note to be thrown away unread. And then I had to remember that the impossible has sometimes the trick of coming to pass to the confusion of minds and often to the crushing of hearts.