Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (11 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

The news of this decree swiftly reached Constantinople and the Greek colonies on the Black Sea and the islands of the Aegean. A mood of pessimism swept the people; old prophecies were recalled foretelling the end of the world: ‘now you can see the portents of the imminent destruction of our nation. The days of the Antichrist have come. What will happen to us? What should we do?’ Urgent prayers were offered up for deliverance in the city churches. At the end of 1451 Constantine dispatched another messenger to Venice with more urgent news: the sultan was preparing a massive build-up against the city and that unless help was sent it would surely fall. The Venetian Senate deliberated at its own speed and delivered their reply on 14 February 1452. It was characteristically cautious; they had no desire to compromise their commercial advantages within the Ottoman Empire. They suggested that the Byzantines should seek the co-operation of other states rather than relying on the Venetians alone, though they did authorize the dispatch of gunpowder and breastplates that Constantine had requested. Constantine meanwhile had no option but to make direct representations to Mehmet. His ambassadors trundled back over the hills of Thrace for another audience. They pointed out that Mehmet was breaking a treaty by threatening to build this new castle without consultation, that when his great grandfather had built the castle at Anadolu Hisari he had made this request of the emperor, ‘as a son would beg his father’. Mehmet’s response was short and to the point: ‘What the city contains is its own; beyond the fosse it has no dominion, owns nothing. If I want to build a fortress at the sacred mouth, it can’t forbid me.’ He reminded the Greeks of the many Christian attempts to bar Ottoman passage over the straits and concluded in typically forthright style: ‘Go away and tell your emperor this: “The sultan who now rules is not like his predecessors. What they couldn’t achieve, he can do easily and at once; the things they did not wish to do, he certainly does. The next man to come here on a mission like this will be flayed alive.”’ It could hardly be clearer.

In mid-March Mehmet set out from Edirne to start the building work. He went first to Gallipoli; from there he dispatched six galleys with some smaller warships, ‘well-prepared for a sea battle – in case that should be necessary’, and sixteen transport barges to carry equipment. He then made his way to the chosen spot by land with the

army. The whole operation was typical of his style. Mehmet’s genius at logistical arrangements ensured that men and materials were mobilized on cue and in enormous quantities with the aim of completing the task in the shortest possible time. The governors of provinces in both Europe and Asia gathered their conscripted men and set out for the site. The vast army of workers – ‘masons, carpenters, smiths, and lime burners, and also various other workmen needed for that, without any lack, with axes, shovels, hoes, picks, and with other iron tools’ – arrived to start the work. Building materials were ferried across the straits in lumbering transport barges: lime and slaking ovens, stone from Anatolia, timber from the forests of the Black Sea and from Izmit, while his war galleys cruised the outer straits. Mehmet personally surveyed the site on horseback and in conjunction with his architects, who were both Christian converts, planned the details of the layout: ‘the distance between the outer towers and the main turrets and the gates and everything else he worked out carefully in his head’. He had probably sketched outline plans for the castle over the winter in Edirne. He oversaw the staking out of the ground plan and laid the cornerstone. Rams were killed and their blood mixed with the chalk and mortar of the first layer of bricks for good luck. Mehmet was deeply superstitious and strongly influenced by astrology; there were those who claimed the curious shape of the castle to be cabbalistic; that it represented the interwoven Arabic initials of the Prophet – and of Mehmet himself. More likely the layout was dictated by the steep and difficult terrain of the Bosphorus shore, comprising ‘twisting curves, densely wooded promontories, retreating bays and bends’ and rising to a height of two hundred feet from the shore to the apex of the site.

The work started on Saturday 15 April and was carefully organized under a system of competitive piecework that relied on Mehmet’s characteristic mixture of threats and rewards and involved the whole workforce, from the greatest vizier to the humblest hod carrier. The structure was four sided, with three great towers at its cardinal points linked by massive walls and a smaller fourth tower inserted into the south-west corner. The responsibility for building – and funding – the outer towers was given to four of his viziers, Halil, Zaganos, Shihabettin and Saruja. They were encouraged to compete in the speedy construction of their portion, which given the tense internal power struggles at court and the watchful eye of their imperious

sultan who ‘gave up all thoughts of relaxation’ to oversee their work, was a powerful spur to performance. Mehmet himself undertook the building of the connecting walls and minor towers. The workforce of over 6,000, which comprised 2,000 masons and 4,000 masons’ assistants as well as a full complement of other workmen, was carefully subdivided on military principles. Each mason was assigned two helpers, one to work each side of him, and was held responsible for the construction of a fixed quantity of wall per day. Discipline was overseen by a force of

kadis

(judges), gathered from across the empire, who had the power of capital punishment; enforcement and military protection was provided by a substantial army detachment. At the same time Mehmet ‘publicly offered the very best rewards to those who could do the work quickly and well’. In this intense climate of competition and fear, according to Doukas even the nobility sometimes found it useful to encourage their workforce by personally carrying stones and lime for the perspiring masons. The scene resembled a cross between a small makeshift town and a large building site. Thousands of tents sprang up nearby at the ruined Greek village of Asomaton; boats manoeuvred their way back and forth across the choppy running currents of the strait; smoke billowed from the smouldering lime pits; hammers chinked in the warm air; voices called. The work went on round the clock, torches burning late into the night. The walls, encased in a lattice work of wooden scaffolding, rose at an astounding speed. Round the site spring unfolded along the Bosphorus: on the densely wooded slopes wisteria and judas trees put out their blossom; chestnut candles flowered like white stars; in the tranquil darkness, when moonlight rippled and ran across the glittering straits, nightingales sang in the pines.

Within the city they watched the preparations with growing apprehension. The Greeks had been stunned by the sudden appearance of a hitherto unknown Ottoman fleet in the straits. From the roof of St Sophia and the top of the Sphendone, the still surviving raised section at the southern end of the Hippodrome, they could glimpse the hive of activity six miles upstream. Constantine and his ministers were at a loss about how to respond but Mehmet went out of his way to tease a reaction. Early in the project Ottoman workmen began to pillage certain ruined monasteries and churches near the castle for building materials. The Greek villagers who lived nearby and the inhabitants of

the city still held these places as sacred sites. At the same time Ottoman soldiers and builders started to raid their fields. As the summer wore on and the crops approached harvest, these twin aggravations turned into flashpoints. Workmen were removing columns from the ruined church of Michael the Archangel when some inhabitants of the city tried to stop them; they were captured and executed. If Mehmet was hoping to draw Constantine out to fight, he failed. The emperor may have been tempted to make a sortie, but was talked out of it. Instead he resolved to defuse the situation by offering to send food out to the building workers to prevent them robbing Greek crops. Mehmet responded by encouraging his men to let their animals loose in the fields to graze, while ordering the Greek farmers not to hinder them. Eventually the farmers, provoked beyond endurance by the sight of their crops being ravaged, chased the animals out and a skirmish ensued in which men were killed on both sides. Mehmet ordered his commander, Kara Bey, to punish the inhabitants of the offending village. The following day a detachment of cavalry surprised the farmers as they harvested their fields and put them all to the sword.

When Constantine heard of the massacre he closed the city gates and detained all the Ottoman subjects within. Among these were a number of Mehmet’s young eunuchs who were on a visit to the city. On the third day of their captivity they petitioned Constantine for release declaring that their master would be angry with them for not returning. They begged either to be freed at once or executed, on the grounds that release later would still result in their death at the sultan’s hand. Constantine relented and let the men go. He sent one more embassy to the sultan with a message of resignation and defiance:

since you have preferred war to peace and I can call you back to peace neither with oaths or pleas, then follow your own will. I take refuge in God. If He has decreed and decided to hand over this city to you, who can contradict Him or prevent it? If He instills the idea of peace in your mind, I would gladly agree. For the moment, now that you have broken the treaties to which I am bound by oath, let these be dissolved. Henceforth I will keep the city gates closed. I will fight for the inhabitants with all my strength. You may continue in your power until the Righteous Judge passes sentence on each of us.

It was a clear declaration of Constantine’s resolve. Mehmet simply executed the envoys and sent a curt reply: ‘Either surrender the city or stand ready to do battle.’ An Ottoman detachment was dispatched to

ravage the area beyond the city walls and carry off flocks and captives, but Constantine had largely removed the population from the nearby villages into the city, together with the harvested crops. The Ottoman chroniclers record that he also sent bribes to Halil to pursue his quest for peace, but this seems more likely to be the propaganda of the vizier’s enemies. From midsummer the gates of the city were to remain shut and the two sides were effectively at war.

On Thursday 31 August 1452 Mehmet’s new fortress was complete, a bare four and half months after the first stone was laid. It was huge, ‘not like a fortress’, in the words of Kritovoulos, ‘more like a small town’ and it dominated the sea. The Ottomans called it

Bogaz Kesen

, the Cutter of the Straits or the Throat Cutter, though in time it would become known as the European castle, Rumeli Hisari. The triangular structure with its four large and thirteen small towers, its curtain walls twenty-two feet thick and fifty feet tall and its towers roofed with lead, represented an astonishing building feat for the time. Mehmet’s ability to co-ordinate and complete extraordinary projects at breakneck speed was continually to dumbfound his opponents in the months ahead.

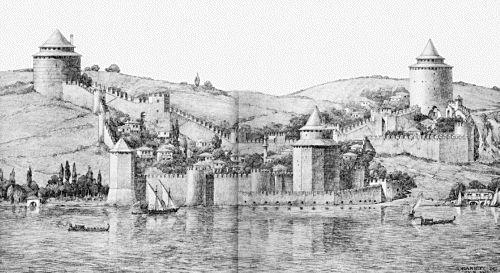

A recreation of Rumeli Hisari, the Throat Cutter

On 28 August Mehmet rode round the top of the Golden Horn with his army and camped outside the city walls, now firmly barred against him. For three days he scrutinized the defences and the terrain in

forensic detail, making notes and sketches and analysing potential weaknesses in the fortifications. On 1 September, with autumn coming on, he rode off back to Edirne well satisfied with his summer’s work, and the fleet sailed back to its base at Gallipoli. The Throat Cutter was garrisoned with 400 men under its commander Firuz Bey, who was ordered to detain all ships passing up and down the straits on payment of a toll. To add force to this menace, a number of cannon had been constructed and hauled to the site. Small ordnance was mounted on the battlements but a battery of large guns, ‘like dragons with fiery throats’, was installed on the seashore beneath the castle wall. The guns, which were angled in different directions to command a wide field of fire, were capable of sending huge stone balls weighing 600 pounds whistling low across the surface of the water level with the hulls of passing ships, like stones skimming across a pond. They were matched by other guns at the castle opposite, so that ‘not even a bird could fly from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea’. Henceforth no ship could pass up or down to the Black Sea unexamined, either by day or night. ‘In this manner’, recorded the Ottoman chronicler Sa’d-ud-din, ‘the Padishah, the asylum of the world, blockading that strait, closed the way of the vessels of the enemy, and cauterized the liver of the blind-hearted emperor.’

In the city Constantine was gathering his resources against a war that now looked inevitable, and dispatching messengers to the West with increasing urgency. He sent word to his brothers in the Morea, Thomas and Demetrios, asking them to come at once to the city. He made extravagant offers of land to any who would send help: to Hunyadi of Hungary he offered either Selymbria or Mesembria on the Black Sea, to Alfonso of Aragon and Naples the island of Lemnos. He made appeals to the Genoese on Chios, to Dubrovnik, Venice and yet again to the Pope. Practical help was hardly forthcoming but the powers of Christian Europe were reluctantly becoming aware that an ominous shadow was falling over Constantinople. A flurry of diplomatic notes was exchanged. Pope Nicholas had persuaded the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick III, to send a stern but empty ultimatum to the sultan in March. Alfonso of Naples dispatched a flotilla of ten ships to the Aegean then withdrew them again. The Genoese were troubled by the threat to their colonies at Galata and on the Black Sea but were unable to provide practical help; instead they ordered the Podesta (mayor) of Galata to make the best arrangements he could with

Mehmet should the city fall. The Venetian Senate gave similarly equivocal instructions to its commanders in the eastern Mediterranean: they must protect Christians whilst not giving offence to the Turks. They knew that Mehmet threatened their Black Sea trade almost before the Throat Cutter was finished; soon their spies would be sending back detailed sketch maps of the threatening fortress and its guns. The issue was coming closer to home: a vote in the Senate in August to abandon Constantinople to its fate was easily defeated, but resulted in no more decisive counter-action.