Counternarratives (31 page)

Authors: John Keene

I answered, “I got to think about it for a little while more, but if you

look at this sign hereӉand I pointed to the cross of light with the faint shape of

a heart hovering just above its center, a forewarning and lamentâ“and here, to the

way the blades is bending outward on either side like an invisible arrowӉurging us

to stay right where we wereâ“and to here,” a patch so dusty it was as if the desert

of solitary death had already laid claim to it, “this is not the time to attack, I

can almost assure you on my parents' and my grandparents' graves of that.” DeVeaux,

who had also walked over, countered without even acknowledging me that my mumbo

jumbo and hoodoo claptrap couldn't be right, that what we needed to do is fight our

way to the next line, lay those Confederates and their French and Mexican

infantrymen low like the reaper, and they all commenced to smiling and clapping,

Johnson, Scott, Shepard, Morris who had his sisters kidnapped into Arkansas well

before the first shot down at Sumter, Wilson, Patterson, Renard, Kelley, even

Bergamire, nearly every last one of them. DeVeaux was on a roll now, his voice a

common preacher's, which is what his father was, Anderson told me the first time I

witnessed him going on like this, soon as he got free the daddy took up the Good

Book and the son intended to follow that profession, these folks from the far

northwestern corner of the state, near Nebraska, though he had shifted into

testifying about how we all needed to go beyond shooting them down, we needed to

kill at least ten apiece, have a slaughter to send a message to Price and Bedford

and all the rest. When he had finally quieted down, Anderson reminded everyone we

had orders to take them prisoner rather than go on a spree.

When he said this last word a few of them guffawed because they hadn't

ever heard that word before, but Anderson was wont to speak real proper at times,

like a dictionary would if a dictionary could talk, which made me think of my old

lady back home. He and Bergamire and a few of the others would take turns teaching

classes early in the morning and by the campfire, on spelling and speaking and math,

not the kind of learning people learned in the fields or in the store rooms in

country towns, but the right way so that you can pen your name when the time came,

and understand what your documents were saying, and count your pay before and after

it hit your pocket, instead of having to rely on them other folks to do so for you.

I found myself growing close to Anderson, and would tell him what I was picking up

so that he could convey it to the rest as if he had somehow assessed it himself,

since they were more likely to listen to him.

But that day was not propitious, and yet Colonel Barrett ordered us to

ready ourselves and proceed against the gray traitors, which meant eight companies

of our United States Colored Troops, which is what we became when the Army

federalized our Missouri brigade, would head with the white 2nd Texas Cavalry

Battalion under the command of Lt. Colonel Branson through Boca Chica Pass to engage

the enemy, driving them back to Brownsville and capturing any we could along the

way. All day we prepared for the evening march, though it was already clear that

four dozen of the white men would have to proceed horseless, but both Anderson and

Bergamire circulated among all the companies to say that as soon as we overtook the

insurrectionists we were to requisition as many of their mounts as we could. Between

readying and packing equipment I sat and composed brief letters, which Anderson

wrote out in his steady hand, to Johnny O., who was with a regiment still stationed

in Tennessee, and to Bessie Amelia, who was raising money for the troops all across

Minnesota and Wisconsin, and to Louisa, who loved hearing about nothing more than

the tedium of my daily military life. A fine rain began falling in the late morning,

and I pointed this out to Anderson, who thought it might let up, but by the time we

had reached the pass, the downpour had thickened into batteries of water, and the

sky cracked open with thunder and foreboding light. Our progress was glacial through

the high, wet grass, which now hid all its secrets, giving off strange waterlogged

sounds and odors, the cattails fizzling like flares, the figworts emitting their

noxsome fragrance, the nightshade extending its mortal embrace, but we followed the

curves of the river throughout the night and caught a brigade of the Confederates

unawares. The Texans took three of the traitors prisoner, and sent some of our men

to husband the supplies from their bivouac, though Anderson had me help set up camp

for the night and read the surroundings for any clues about the following day.

I woke that morning and studied the omens, which were ill but not fully

open to interpretation, so I kept them to myself. By midday we were creeping on our

hands and knees like turtles across green expanse at the base of Palmito Hill when a

fusillade, followed by a brigade of Confederates, engaged us. I usually kept to the

rear as I was ordered to, but Anderson urged several of us to crawl out to the far edge

of the field, near the river, where there was a stand of Montezuma cypresses, which

I did and when I rounded them flat on my stomach, creeping forward like a panther I

saw it, that face I could have identified if blind in both eyes, him, in profile,

the agate eyes in a squint, that sandy ring of beard collaring the gaunt cheeks, the

soiled gray jacket half open and hanging around the sun-reddened throat, him

crouching reloading his gun, quickly glancing up and around him so as not to miss

anything. I glanced behind to see if Anderson was nearby, but he and most of the

rest were proceeding to the north of me, along the open field of battle, a blue line

undulating forward in the high grass, their mismatched uniforms behind the white men

in their blue streaming like waves on the one side and the gray of the

insurrectionists on the other, the gunfire crackling like the announcement of the

end of something terrible, and I looked up and he still had not seen me, this face

he could have drawn in his sleep, these eyes that had watched his and watched over

his, this elder who had been like a brother, a keeper, a second father as he

wondered why this child was taking him deeper and deeper into the heart of the

terror, why south instead of straight east to liberation, credit his and my youth or

ignorance or inexperience, for which I forgive him and myself but I came so close to

ending up in a far worse place than I ever was, and I heard Anderson or someone call

out in the distance, and raised my gun, bringing it to my eye, the target his hands

which were moving quickly with his own gun propped against his shoulder, over his

heart, and I steadied the barrel, my finger on the trigger, which is when our gazes

finally met, I am going to tell the reporter, and then we can discuss that whole

story of the trip down the river with that boy, his gun aimed at me now, other faces

behind his now, all of them assuming the contours, the lean, determined hardness of

his face, that face, there were a hundred of that face, those faces, burnt,

determined, hard and thinking only of their own disappearing universe, not ours,

which was when the cry broke across the rippling grass, and the gun, the guns, went

off.

Â

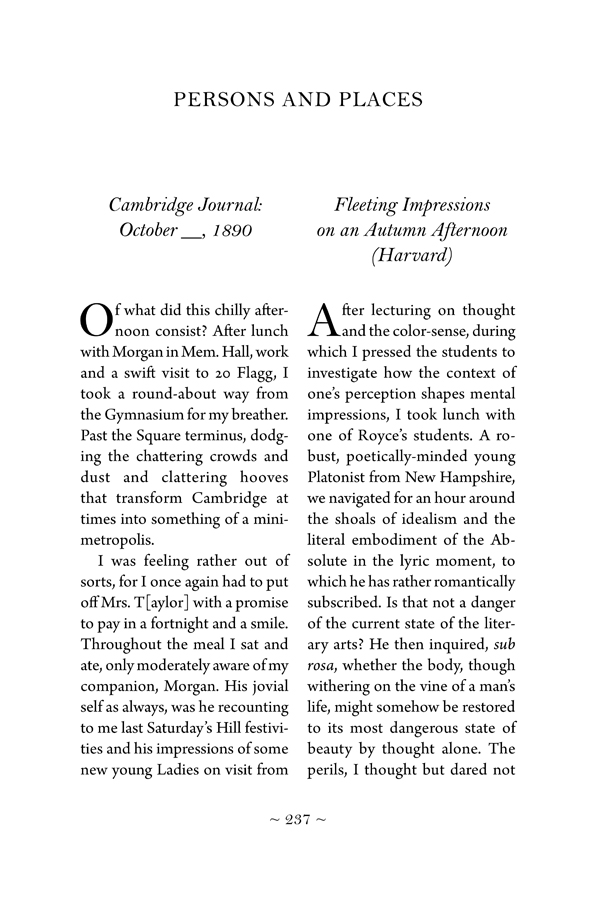

PERSONS AND PLACES

Editor's note: "Persons and Places" appeared in the print edition of

this book as two columns, side by side. Due to technical limitations, the story

appears here as one single column.

Cambridge Journal: October

__, 1890

O

f what did this chilly

afternoon consist? After lunch with Morgan in Mem. Hall, work and a swift visit to

20 Flagg, I took a round-about way from the Gymnasium for my breather. Past the

Square terminus, dodging the chattering crowds and dust and clattering hooves that

transform Cambridge at times into something of a mini-metropolis.

I was feeling rather out of sorts, for I once again had to put off Mrs.

T[aylor] with a promise to pay in a fortnight and a smile. Throughout the meal I sat

and ate, only moderately aware of my companion, Morgan. His jovial self as always,

was he recounting to me last Saturday's Hill festivities and his impressions of some

new young Ladies on visit from Philadelphia, or did I only imagine hearing him say

this? In truth I was concentrating on my questions for the coming meeting of the

Philosophical Club, where Santayana, that new graduate student and my likely tutor,

is set to speak on “Spinoza and the Ethical Sensibility.”

Indeed, as I was passing down Mount Auburn Street, I spotted his

black-clad figure floating by. Ghostly, yet swarthy, an Iberian by birth, though

perhaps not in temperament, something dangerous and daring in those black eyes. Our

gazes met, glancingly. As he has been wont to do whenever we have seen each other,

he abruptly turned away, striding faster than before he had caught sight of me. I

continued on toward the river, where I thought I might walk for a while and observe

the currents slowly pulling whatever traffic still lingered toward the

Institute.

Why does he glower so? Is it fear, for certainly he has seen a

Negro before, or can it be an acknowledgement of how deeply we are linked? Or does

he, like nearly all the rest of them,

not really see me

at all

?

Of

course there will be scant possibility of a friendship. Be he a Latin or the Statue

of Liberty; for even Professor [Wm.] James, in all his eccentric allegiance, admits,

when we are at the same table, of those unshakable walls that separate us. Still I

know that at some point soon I shall have opportunity to probe his mind, share my

inquiriesâ

he and I alone, in an upper room

âand he will come to

appreciate our common humanity.

For fifteen minutes thus I stood, gathering impressions in the chill,

until true cold settled in. Then I hurried back, darting between carriages and odd

fellows, almost missing the news stand. I could only glimpse the evening headlinesâa

human bullet runs the 100 yard dash in under 10 seconds; the Abyssinian War

continues; another lynching

â

making swift mental notes on all issues

pertaining to my people, even though the various other national and international

events of the past few weeks have not yet had a moment to

sediment. . . .

Fleeting

Impressions on an Autumn Afternoon (Harvard)

A

fter lecturing on

thought and the color-sense, during which I pressed the students to investigate how

the context of one's perception shapes mental impressions, I took lunch with one of

Royce's students. A robust, poetically-minded young Platonist from New Hampshire, we

navigated for an hour around the shoals of idealism and the literal embodiment of

the Absolute in the lyric moment, to which he has rather romantically subscribed. Is

that not a danger of the current state of the literary arts? He then inquired,

sub rosa

, whether the body, though withering on the vine of a man's

life, might somehow be restored to its most dangerous state of beauty by thought

alone. The perils, I thought but dared not say, of a little Wilde or Swinburne, a

dose of Pater or, forgive me, William Shakespeare. . . .

Later, as I strolled along Mount Auburn Street, quietly composing,

concepts racing in my head like the regattas these New Englanders love to hold, I

noticed him again. The intense young colored man, a Negro most certainly, brow high,

stern mien, walking briskly toward the river, his eyes fixed upon an invisible

target, an imaginary star. This

Du Bois

, who, I am told by that collector

of personalities, William James, fashions himself a philosopher, though gifted with

scientific and other facilities. It is true that I have noted him haunting the

precincts of the Yard, books peeking from his tattered leather satchel, his cheeks

the color of tea into which several tablespoons of sweet cream have been poured,

that gaze pressing intently toward some hidden point. Several times we have glimpsed

each other, in wary appraisal, and I have, I shall not dissemble, hurried on.

Perhaps he recognizes me as one of those who professes, an admirer of mental

industry whatever the outward appearance of the bearer; or perhaps through some

profounder spiritual auscultation, divined the passion and ritual in my gait.

This

jeune philosophe

, like the other Negro students, the

handful of unassimilable Easterners, Chinese, Mexican boys, must by necessity

subsist on an island even more remote than that on which I sojourned during my College

days, within this larger crimson archipelago. At one level, I imagine it would

provide a place of refuge and some element of happiness for their small and scorned

society.

He observes me as if he has already examined the catalogue of ideas and

impressions which I shall tell him when we eventually speak, of the gulf between the

true-self and the world outside and how the mind, through its exercises, bridges it;

of the forests rising around the language of the physicist's thought; of the

importance of doubt in the philosophical method;

of those fugitive joys and

sincere ecstasiesâthat heaven that lies in the heart of the earth

; of my

own long and unfolding exile.

Editor's note: See the following images for the original layout: