Counternarratives (34 page)

Authors: John Keene

Open your mouth as if you intend to swallow. You set the glass down and

head for the door. “Excuse me, Sir, but you finished?” the young man, so light only

his features, hair texture reveal his story, murmurs politely, “Can I get you

anything else, Sir, send something up to your room?” You pause, look him over, see

the eyes catching yours, another time, you think, shake him off, force a half-smile

when you catch his flash of recognition, or perhaps it's just that broader sense of

a link mixed with abstract solidarity, so common wherever you see each other, our

people, even if no one else fully sees you, until the stain of disdain seeps in,

perhaps the young man stood at the doorway as you regaled everyone last night with a

few of the songs your fingers played from memory since your mind would not

cooperate, you could see your mother beaming from her seat as you completed “Under

the Bamboo Tree,” nodding, clapping, her eyes telling you that everything was all

right although it wasn't, it isn't, perhaps years before he saw you staring back

from a handbill, contentedly, unlike now, and he too secretly blames you, they all

do, for how you all are viewed? You pass into the alcove, past the check-in desk.

The doorman, dark as a pneumatic tire, in elaborate livery despite the heat, swings

the door open. You flinch, seeing your own face staring back, your mug never so cool

or placid anymore except in photographs, engravings, the same wide forehead, broad

slender lips, lantern eyes bearing something outward while beaming back in, making

you glad no mirror's nearby, that you never saw yourself on stage, made up and

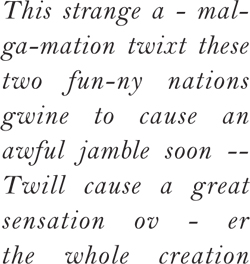

masked, always masked, that awful jamble thankfully never captured for the

Nickelodeon or a gramophone, you recover and extract the sole billâ$10âyou have and

some coins from amid the goldweight and the paperweight you stuffed this morning in

each of your trouser pockets and place the money in that other palm, sheathed in

white cotton beneath which you know lies a square of pink ridged with brown like

your own, as your grip tenses, relaxes. The hurdy gurdy in your head churns on.

“Thank you so much, Sir. Shall I call you a driver, Sir?” the doorman asks, assuming

correctly that you will not want to walk in this heat through the streets toward

downtown, or perhaps you might be heading to Athens or across the river to Hudson.

No thank you, you mean to say, if you there, staves and quarter notes stalling your

tongue, spilling out, you think you assure the doorman you're fine with a wave and

head in the opposite direction, away from the town and river, northwest instead,

over the meadow toward Main.

The first response is to struggle but you should stifle it. On the

lawn as you pass a seated trio is laughing. Beneath them spreads a lake of gingham.

You know the couple, initially because of your stays here, later after time spent

with them in the City and at their home, Luther and Anna, they travel down from

Buffalo where he has a general practice and also runs the local colored paper and

she teaches school. You chatted with them briefly yesterday when you got in. The

other woman, pretty enough to be a movie star if colored women starred in movies,

looks familiar but you cannot place her. Gwendolyn, they introduce her, from Boston,

she was here last year with her parents, the father a bishop of some sort, now you

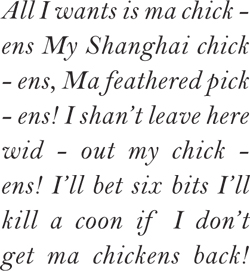

remember, I'll bet six bits she was one of Anna's former students you'd said to

yourself before you met her then, they are trying to make

that kind

of

introduction again, she straightens the ribbons in her loose black locks before you

take her hand and drop it. She is saying something to you about your songs, your

shows as you think you hear Luther ask, Why don't you join us, Bob? he and Anna

nodding, she adds, We'd like that, we haven't hardly seen you since you arrived. You

cannot hear what Gwendolyn is saying, it's as if someone has a trombone against your

lobes, playing an ostinato, the same long, low phrase, then the original song comes

back and you feel light, almost giddy, whisper you are going to walk over to the

creek, if you see yourself going along so, Luther looks at Anna, they lift

themselves up to join you. You touch your hairline where the music threatens to

erupt, as they gather up the knives and forks, the bread and honey, the corked

bottle of lemonade, place it in the basket, fold up the cloth, Luther's and Anna's

manners each as precise as they always have been, as anyone would expect of folks of

their station. Gwendolyn hangs back, fanning herself, her eyes trained on you. You

mean to say something about the weather, but no words emerge, nothing about the

food, the staff, your mother, Luther's suit, Anna's dress the shade of

crème

anglaise

, Boston, Harlem, Rosamond or Jimmy, the Sambo Girls Company or

your other efforts, touring, business in general, Gwendolyn in whom you'd never be

interested, your other

friends

in New York you would never discuss let

alone hint at, the train ride up, the last few months, years, the long winters of

blue periods that have plagued you even before the music could not be turned off.

Only a sound that sounds like the inside of a sound, a not-whistle, a not-warble,

not-words, a code, a cloud of could and cannot, and Luther laces his arm in yours,

Anna close by on his other side, the basket on her free arm, Gwendolyn somewhere

behind them, humming, why is she humming? two live as one, she's humming one of your

tunes, or is that you and the sound is escaping you, as it sometimes does, if you

like a me and I like a you, as you proceed across the grass to the road.

There is no way to counter the initial pain, a burning sensation,

but eventually it will subside. Luther's arm slows you, stops you here at the

roadside, you pause to pat your cheeks dry, your chest, the late afternoon heat is

intensifying, you all pause as cars and carriages barrel by. Anna is talking again,

something about her people who came up from Richmond to visit, some other folks they

met during a trip to Ottawa, the ones appearing every day in Buffalo from Kentucky

to Kingston, their planned cruise to Venezuela, what do you think about all the

lynchings so far this year, what do you think about the new National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People in New York, those white liberals and our folk who

belong to the upper ten, Rosamond and Jimmy know people involved with it, you do

too, what do you think, Luther's agreeing with everything she says, his voice like

hers softening as if to distract you, and though you cannot hear anything they're

saying clearly anymore, hear anything beyond this interior echo, though you perceive

somewhere in their tone something else in the rhythms of their words, the blade of

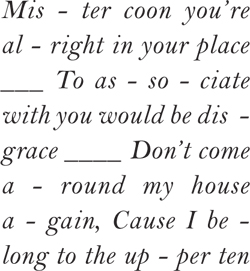

rebuke, not even friendship can hide it, you know what you did, they want to say,

what you wrote, how you helped to sow this sickness even in the minds of your own,

you know you did and tighten your fingers on the weights, so solid the gold, so

smooth the glass, sometimes you're up, sometimes you're down but they are anchoring

you right here, what do you think, as you squeeze on the weights what do you think

and you do not. Gwendolyn, whose voice tinkles like a triangle slightly out of tune,

has taken your elbow in her hand, fanning you as she inspects your eyes, your

trembling lips. She asks if you would like a drink of water. Luther pats you on the

back and suggests you all continue to the creek, sit on its banks briefly and rest,

then return to the hotel. You want to say you were heading there anyways, the shade

of the paper birches and slippery elms letting you cool off before you continue on

your intended journey. You wag your head, something issuing from your insides,

something that is and is not the noise buzzing in your brain, your throat, all down

the column of your spine, into your toes, you can almost arrest snippets, you know

these songs by heart, how many times did you perform them by heart, stand before

that wall of stares and pull everything from your heart, by heart, record them by

heart, you could put on a show right now by heart, as you did last night by heart,

here on this greensward by heart, anywhere you wanted to by heart, like you used to,

like you did in the park by heart that night and the man, that midnight man standing

above you just turned on his heels and ran, you squatting there and could not stop

yourself and the entire routine of

A Trip to Coontown

came out, every

single note, not one missed, and it wasn't until a small crowd out seeking just like

you had surrounded you, their shapes stirring the black, that you realized where you

were. Luther guides you to a spot they've picked, Gwendolyn dresses it with the

gingham cloth.

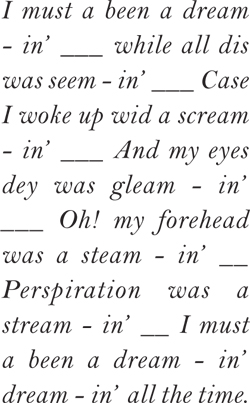

As your mind goes black, begin counting backwards. The years?

Where have they gone? 1911, 1910, 1909, nobody knows the trouble . . . finally words

erupt from you: “I'm going to go for a swim.” They look puzzled, Anna is whispering,

reminding her husband she did not bring her swimsuit and you all can try tomorrow at

the river, but you hurtle forward down the slope into the water. “Bob,” Luther is

saying, “Bob,” and you're pantomiming, because no more words will flow, only the

music, forehead steaming, you are miming swimming, waving to them and grinning, that

wit and playacting that always got everyone, this time without the kohl or charcoal

corking and the floppy hat, “Bob,” and you do the crawl and the sidestroke and the

breastroke, your arms windmilling the air, can feel the creekwater in your shoes,

halfway to your knees, your drawers, if you like a me, eyes gleaming, cold, and I

like a you, you can hear it now too, the creek, streaming, the water, no wig or

whiskers now, no polish, must a been dreaming, never again, “Bob, come on out,”

Luther is walking toward you, never again to croon a coon song, Uncle Rastus, you

wave him off, the water at your chest, dreaming all the time you tried, Bob come on

out, how you tried but it kept leaking in, moon don't make me wait in vain tonight,

no whistling coon no more, no cane or jig now, oh soul you cut it out soon as you

could, so loud, the music and those voices, Bob, all this was a seeming, you ducking

beneath the surface, the hot hate floating, away, swimming away, No, Bob, maybe Anna

now, someone crying out and crying, Gwendolyn please go get someone from the hotel

and Mrs. Isabella, sinking, go soul, under the bamboo tree, Zulu from Matabooloo

they never knew you, blues, the true you dreaming the true you nobody's looking

nobody knows no coon no more two live as one they will never harm you at all fly

soul no coon a man bending down into the mud it's quickest someone once advised you

when you completely let go, because the surface appears tranquil but beneath there's

the undertow, and you shut your eyes and lay your head back, knowing the current and

weights in your pockets will do most of the work, allow the foliage below you its

ready embrace, but just in case you open your mouth because you intend to swallow,

battling then defeating the impulse to struggle, you feel the first stabs of pain, a

burning in your chest no worse than the pain of that music you knew best, eventually

it too will subside, that bonfire, the nightmare track as your mind turns back into

the blackness you count backwards joining in your song no coon no more nobody knows

the trouble I've seen nobody but Jesus if you get there before I do tell all 'a my

friends I'm coming until the music breaks into a screaming silence that if you could

describe it in a word would be no word or note or sound at all but fleetingly,

freeingly

cold. . . .