Crime at Christmas (5 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

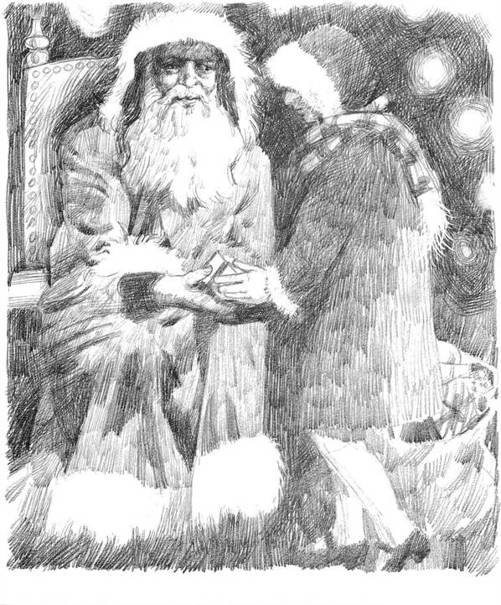

At the end of the cavern, on a platform festooned in holly where children

could mount the two steps and whisper their wishes, sat Father Christmas

himself.

At Father Christmas's right hand was a table piled with small gift-boxes

wrapped in bright paper.

Even as Pollard stared, a little girl of possibly 12 years walked up the

steps.

She was very dainty in white fur jacket and white cap. Her long yellow

curls fell forward as she bent to whisper.

Father Christmas chuckled. He nodded. Selecting a gift-box from the table,

he turned back in one vast beam to give this present to his small friend. And,

as he did so, Father Christmas's large left eyebrow closed down as though he

leered or held an eyeglass.

'Uncle Bob!' screamed Tommy. 'Did you see it? The funny eyes. You

remember. You said The Colonel. . .'

Detective Superintendent Pollard, Criminal Investigation Department,

quickly turned to the boy and hushed him.

Then, in a flash, he charged.

He was a big man. He avoided the children, but parents scattered before

him like skittles. There was a crash as he jumped up on the platform.

'I don't think you'd like that one, my dear,' he said pleasantly to the

little girl, and nodded towards the box held out in Father Christmas's hand.

In a low voice he added: 'Better give me the diamonds, Colonel. As for

you, Shorty. . .’

The little girl lifted sweet and innocent eyes.

'Coppers!' she whispered, showing her teeth. 'He's a copper, Colonel;

that's what the so-and-so is.'

'When a man is called Shorty,' said Pollard in the same low tone, 'it may

not mean much. But when a woman is called that, as we ought to have realized,

she must be almost a dwarf. I suppose your little-girl clothes, and the blonde

wig, were in that parcel? And you changed in the dress-shop? Nobody would

notice a 12-year-old; the police weren't to blame for that mistake.

'But we were to be blamed about you, Colonel,' he added. 'Omnium's opens

at nine; we thought everybody had to be on duty then. And yet, as you can see

by a sign over the pay-box back there, this grotto doesn't open until eleven.

You could slosh Van Bele and get back on time. Your Father Christmas suit was

left in the phone-box and all you had to do was nip into it while the crowd

barged around outside and our men were still trying to push their way through,

and then simply step out of the booth. It was a risk, but it worked. In any

case, when the police finally reached the phone-box they weren't looking for

Santa Claus with all the trimmings, they were trying to spot The Colonel in

smart suit and overcoat.'

In that paralysed scene, the bright-coloured box was still held out in

Father Christmas's hand. 'Cut and run for it, Shorty!' he chuckled. 'I hate to

spoil the kids' Christmas, but I'll get this copper before they get me.'

'Think so?' smiled Pollard. 'You haven't a chance against me and you know

it. I can't help you. But it's Christmas—and I can help Shorty get away. Fair?'

'Turn it up, copper!' sneered the sweet-faced girl—and yet an edge of hope

appeared in her face.

'Give me the box,' Pollard said. 'If the diamonds are inside, she hasn't

officially received them. She can go now and take her chance of being picked up

later. Fair?'

Father Christmas looked warily at Pollard before exchanging a knowing

glance with the girl.

Then, without a word, he handed over the box to Pollard.

As he did so, he noticeably sagged with relief behind his beard.

Then his rich, soothing, cultured voice rang out.

'Ladies and gentlemen!' carolled Father Christmas. 'This gentleman is

particularly anxious to have this box. I hope he finds in it what he's looking

for.

'Personally, I'd rather give the little girl another box. Here it is. Now

hurry down the steps, and out of this store. Others are waiting.'

At the sight of a monocled Father Christmas, a ripple of laughter spread

out over the grotto, carrying with it the spirit of Christmas as children

crowded forward.

Tommy, pushing forward, hardly noticed that Elsa was no longer watching

Father Christmas.

She was looking at Pollard—and in her eyes shone admiration—and

unconcealed adoration!

-

Santa-San Solves It

by

JAMES MELVILLE

T

HE FIRST

time I came across

a book

by

James Melville

(real name Peter Martin, b. 1931) I was reviewing crime fiction for one of the

literary monthlies and had had it up to the back of my throat, and beyond, with

oddball and/or exotically ethnic sleuths.

As each new parcel arrived I knew I was doomed yet again to deal with a

fresh crop of antique-dealer detectives, pet-shop owner detectives, mortuary

attendant detectives; a dreadful parade of Philippinos, Basques, Romanys,

Liechtensteiners, and pure-bred lnuits—all of whom would (naturally) bring

their own special talents or peculiar native wit to bear on the knotty and

murderous problems posed by their creators (most of whom, you bet, would have

had but a passing acquaintance with the profession or country of their choice,

merely bowing to one of the unwritten rules of mystery fiction: make your

manhunter

colourful).

So a Japanese

detective—all those incomprehensible rituals, all that tedious

inscrutability—was the last thing I needed.

But I was wrong. The book was Melville's third novel,

A Sort of Samurai

(1981), and from

the first page I was entranced. So entranced that I didn't offload it on my

usual bookshop (at the reviewer's perk of a third of the published price) but

kept it, located the first two, and have bought each new Melville—on

publication, with my own money (greater love hath no fan)—ever since.

Melville writes police procedural, and a good deal of the charm of the

series lies in the fact that the police, led by Superintendent Tetsuo Otani of

the Hyogo Prefecture, with full supporting cast, proceed in an utterly alien

manner. To the Occidental eye, anyhow.

If that were all, Melville's series would be just the same as any other

foreign-cop series—often, merely irritatingly different. But James Melville is

a fine writer with a dry sense of humour and a neat (as neat as a

netsuke,

to use the

shorthand of my reviewing days) line in subtle characterization. And he loves

Japan. As you read, you begin to, too.

There's precious little blood in an Otani story, few car-chases, and the

level of violence is abysmally low. But who cares? All these ingredients may be

had elsewhere, in abundance. The manners and mores of Japanese society are

described so compellingly, the mysteries to be solved posed in such a delicate

and ironical manner, the running cast of characters is brought so sharply to

life (I'm currently fascinated by the relationship between the highly

intelligent and attractive young policewoman Junko Migishima and her somewhat

put-upon husband, who is experiencing at first-hand precisely what the phrase

'new women' means) that, in short, Otani is just the ticket for the palate

bruised and brutalized by the crash and rush of the average modern detective

novel.

When I asked James Melville to write an original Otani story for

Crime At Christmas

he was distinctly

apprehensive. 'I've never written a short story before', he said. You'd never

know it. He really ought to write more. . .

T

RY IT

just once more,' Inspector Kimura said

encouragingly. 'Your "Jingle Bells" is fine.'

'Hardly surprising. Everybody knows

Jinguru Beru

; you can't get

away from the wretched tune. Television, department stores, coffee shops.

They've been playing it twenty-four hours a day since November.'

'True. So you've no worries on that account. All the children will join in

at the top of their voices and you'll hardly be heard anyway. No, it's the

"Ho! Ho! Ho!" you need to work on.'

Superintendent Tetsuo Otani glowered first at his trusted lieutenant and

then at his shoes. 'Ho! Ho! Ho!', he said in an undertone, sounding like an

embarrassed Englishman repeating the word 'whore'. 'It's no good, I can't and

won't say it. It's not as if it means anything, anyway.'

'Of course you can, Chief, you can't let the Rotarians down. But do try to

look a bit more cheerful. It's a Christmas party you're going to, not a

funeral. And you'll only be centre stage for twenty minutes or so after all.'

'Half an hour at least, the chairman of the social work sub-committee

said. Dressed up like an idiot. All this Santa Claus business is a foreign idea

anyway,' Otani complained. 'I don't see why they picked on me. There are two or

three foreign Rotarians in other clubs in Kobe who'd probably have been only

too glad to volunteer. And lots in Osaka. Ho Ho Ho indeed.'

Kimura sucked in his breath and shook his head. Nothing could be done with

the superintendent when he had made up his mind to be mulish. 'Oh, well,' he

said, 'I expect it'll be all right if you ring your bell while you say it. And

the beard will cover up your expression, I suppose. Now, can I talk for a

minute about Mrs Bencivenni?'

Otani sat back in his chair, his black look replaced by one of mild

interest. 'I've heard that name somewhere recently,' he said. 'She's. . . yes,

of course, isn't she the women who runs the place?'

'The children's home where your Rotary Club is paying for the Christmas

party, yes, but she doesn't exactly run it, she's the president of the

committee of management. Fund-raisers, in effect. There are several foreign

ladies on it. Goes back to the origins of the place during the occupation, when

most of the kids were mixed-blood.'

'Babies bar-girls had by American GI's, you mean. I always felt sorriest

for the ones who were half black. Incredible to think some of them must be

getting on for forty now. Can't be much of a life for them here, neither the

one thing nor the other. We Japanese have a bad record with misfits, Kimura.'

Otani sighed and Kimura nodded briefly, still after years of close

association capable of being surprised on occasion by subversive remarks from a

man he usually thought of as being a thoroughly old-fashioned Japanese with

predictable prejudices. 'Well, it's an odd coincidence that I should be going

to this charity place of hers, I suppose, but worrying about foreigners is your

job. Why do you want me to hear about this Bencivenni woman of yours?'

'Funny you should mention mixed-blood children, Chief. You must be

psychic. Mrs Bencivenni was one of them herself, brought up in that self-same

children's home. It was called the Nada Orphanage in those days. Her father

couldn't have been black, though, she's fair skinned, looks quite European.

Good-looking woman, in fact, speaks perfect Japanese. Middle to late thirties.'

'In that case be specially careful, Kimura. You know how susceptible you

are. The lady has a husband, I presume?'

'She does indeed. Luciano Bencivenni, an American citizen, aged fifty-six,

known as Luke. He's the problem.'

'Ah. Bigger than you, is he? Inclined to be jealous?'

Kimura cast an ostentatious glance heavenwards and pressed on, privately

relieved that Otani seemed to be regaining his normal equable humour. 'Mr Bencivenni

used to be a bank official, but has been in business on his own account for a

number of years as a personal financial consultant. In practice he's a kind of

all-round adviser to the western community here in the Kobe-Osaka area.

Prepares tax returns for Americans, sells life insurance, arranges long-term

investment plans for children's school and college fees and so forth. He's the

agent for a number of American and British insurance companies. And Mrs

Bencivenni thinks he's planning to kill her.' Kimura paused, wondering whether

his chief's renowned poker face would be proof against such an artfully sprung

surprise. It was.

'Does she indeed? How do you know?'

'She turned up downstairs here at headquarters yesterday and asked to

speak to a senior officer in confidence about a matter involving the foreign

community. I interviewed her and she told me herself.'

'Do you believe her?'

'Well, she's certainly not off her head, and she's obviously worried sick.

What she told me was disturbing enough for me to organize a certain amount of

digging, and I think you ought to know what we've come up with.'

'Stand

still!'

Hanae commanded,

and Otani froze. She very seldom used that particular tone of voice, and when

she did it was advisable to do her bidding. The Father Christmas outfit had

been delivered to the house earlier that day, by Hanae's friend Mrs Hamada, who

was also married to a Rotarian and who from time to time spoke vaguely of connections

in show business. Hanae took it for granted that it was these which gave her

access to such colourful fancy dress.

Over a cup of coffee they had unpacked the exotic garments, shaken out the

folds, and agreed that the ensemble must have been made for a giant. They'd

both giggled helplessly when Mrs Hamada tied a doubled-up

zabuton

cushion to her

tummy and sportingly modelled the voluminous tunic, and after subsiding agreed

that it would need a huge tuck in the back. The eighteen inches or so of excess

length presented no problem: it could be hitched up as though the garment were

a

kimono.

Three safety-pins later, Hanae rose from her knees, stepped back and

surveyed her husband. 'It won't take long to tack up,' she said, obviously

having forgiven him for fidgeting.

'Why don't you just leave the safety-pins in? You won't be able to see

them under that sash thing.'

Hanae decided to ignore such a heretical suggestion, and eased the

ungainly garment off Otani's shoulders. 'Why didn't you tell me that some of

the other Rotary wives are going to be helping on the day? I'd have been glad

to take some cakes or something along.'

Something remarkably like a blush darkened Otani's naturally swarthy face.

'Because I shall feel quite enough of a fool as it is without you being there

to watch,' he mumbled.

'Ah. I thought it might have been that you wanted the glamorous Mrs

Bencivenni all to yourself.'

Otani gazed at her in amazement as he slowly lowered himself to the

tatami

matting, reached

for the

sake

flask on the low

lacquer table and refilled his cup. 'What on earth do

you

know about Mrs Bencivenni?' he enquired

as Hanae looked down at him, her arch little smile fading rapidly. 'Have you

met her?'

'No. Er, have you?'

'No. So there's no need to look so tragic. But I have been hearing quite a

lot about her recently. From Kimura. Presumably you and Mrs Hamada have been

discussing her too. What did she say? Sit down and have some

sake.'