Crime at Christmas (8 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

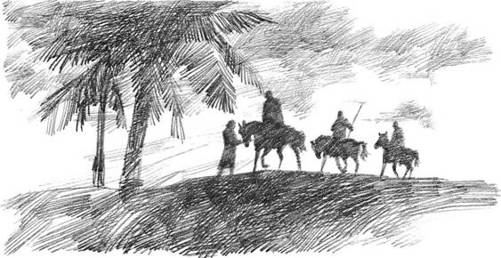

The Three

Travellers

by

EDWARD D. HOCH

S

OMEONE

should swiftly ship a protection order

on Edward D. Hoch (b. 1930). He's one of a kind. At least, I don't know of any

other writer who these days makes a serious living out of writing short

stories, and only short stories.

And not just any old short stories, either, for Ed Hoch has a most

peculiar mind. A hefty proportion of his vast output is in the toughest mystery

sub-genre of them all: the Impossible Crime.

Ed Hoch is very good at the Impossible Crime. Here's one. A man staggers

from out of a small curtained voting-booth mortally wounded from a

dagger-thrust to the heart. He dies within seconds. He was alone in the booth;

there were eight people in the room outside, none of whom killed him; the knife

is nowhere to be found. And what about this one. An armed policeman is alone

with a woman in a locked room. A shot crashes out, the woman lurches backwards,

blood spurting from her chest. The cop didn't kill her, although his gun—which

he drew only after the shot—has been fired. Yet no one outside the room killed

her either. Ed Hoch is

awfully

good at the Impossible Crime.

And not simply because he can think up wild and way-out situations time

after time (and he can), but because the wildest, most way-out situations

invariably have neat and logical and perfectly fair solutions. The kind of

solutions that make you strike your forehead with the palm of your hand and

mutter, through gritted teeth, 'Of

course!’

He's awfully good too at coming up with fresh and original, not to say

bizarre, series-characters. There's Ben Snow, a cowboy detective who is

possibly the reincarnation of Billy the Kid; Simon Ark, who pursues Ancient

Evil inexorably, and who might, just might, be 2000 years old; Dr Sam

Hawthorne, whose home-village of Northmont certainly contains more screwball

murderers than the rest of New England put together (I'm tempted to say the

rest of the United States); Nick Velvet, the thief who hires himself out to

steal worthless items only (a toy mouse, the water from a swimming-pool, the

dust from an empty room) for 20,000 bucks a time—and gets plenty of takers.

Ed has been other things than a writer, but not many. He was in the army

in the early 1950s, worked as a researcher in a public library, did a stint at

a paperback publisher's, ground out copy for an ad agency. But mostly, since

his first sale in 1955, he's written, and what he's written has mostly been

mystery fiction, rarely less than three thousand words long, rarely more than

eight.

I don't know how many stories there have been (I often wonder if Ed

himself knows), but the total, as I type these words, will be about thirty or

forty less than the total when these words are actually printed, fifty or sixty

less than when they're finally read. It can't be too long before he reaches

that magic figure of 1000 short stories.

It might be thought that any writer with that total under his belt must

have repeated himself, and to be sure Ed has his favourite themes, his old

dependables (he's quite fond of fishing-rods, I've noticed; it had never really

occurred to me how invaluable a fishing-rod can be when you have murder on your

mind). Yet again, and again, and again, and seemingly effortlessly, he comes up

with the new twist, the fresh slant, the novel approach (the late John Dickson

Carr once said of him, 'Satan himself could be proud of his ingenuity').

Who else but Ed Hoch, when faced with the prospect of an importunate

editor and a Christmas-issue deadline coming up fast, would reject footprints

in the snow, dead Santa Clauses, exploding parcels, killer Christmas trees, and

present a tale that on the face of it doesn't seem to have a lot to do with the

Festive Season at all. . .

N

OW

the three had

journeyed several days when at last they came upon the Oasis of Ziza, and

Gaspar who was the wisest of them said, 'We will rest our horses here this

night. It will be safe.'

'Safe for horses and men,' Melchior agreed. 'But what of the gold?'

'Safe for the gold also. No one knows we carry it.'

The sun was low in the western sky as they approached, and Gaspar held up

a hand to shield his eyes. It would be night soon.

A young herdsman came out to meet them and take their horses. And he said,

'Welcome to the Oasis of Ziza. Have you ridden far?'

'A full moon's journey,' Gaspar replied, speaking in the nomadic tongue.

'What is your name?'

And the herdsman answered, 'They call me Ramoth, sire.'

'Here is a gold coin for you, Ramoth. Feed and water our mounts for the

journey and another will be yours on the morrow.'

'Which way do you travel, sire?'

'Towards the west,' Gaspar said, purposely vague.

When the young herdsman had departed with the horses, fat Balthazar said,

'I am not pleased, Gaspar. You lead us, it is true, but the keeping of the gold

is my responsibility. And travellers guided by the heavens would do well to

journey by night.'

'The desert is cold by night, my friend. Let us cease this bickering and

settle ourselves here till the dawn.'

Then Melchior and Balthazar went off to put up their tent, and Gaspar was

much relieved. It had been a long journey, not yet ended, and he treasured these

moments alone. Presently he set off to inspect the oasis where they would spend

the night, and he came upon a stranger who wore a sword at his waist.

'Greetings, traveller,' the man said. 'I am Nevar, of the northern tribe.

Do you journey this route often?'

'Not often, no. My name is Gaspar and I come with my two companions from

the east.'

Nevar nodded, and stroked his great growth of beard. 'Later, when the sun

is gone, there are games of chance—and women for those who have the gold to

pay.'

'That does not interest me,' Gaspar said.

'You will find the companionship warming,' Nevar said. 'Come to the fire

near the well. That is where we will be.'

Gaspar went on, pausing to look at the beads and trinkets the nomad

traders offered. When he reached the well at the far end of the oasis, he saw a

woman lifting a great earthen jar to her shoulder. She was little more than a

child, and as he watched, the jar slipped from her grasp and shattered against

the stones, splashing her with water. She burst into tears.

'Come, child,' Gaspar said, comforting her. 'There is always another jar

to be had.'

And she turned her wide brown eyes to him, revealing a beauty he had not

seen before. 'My father will beat me,' she said.

'Here is a gold coin for him. Tell him a stranger named Gaspar bumped you

and made the jar break.'

'That would not be true.'

'But it is true that I am Gaspar. Who are you?'

'Thantia, daughter of Nevar.'

'Yes, I have met your father. You are very lovely, my child.'

But his words seemed to frighten her, and she ran from him.

Then he returned to the place where Melchior had erected their tent. They

had learned from past encampments to leave nothing of value with the horses,

and Gaspar immediately asked the location of the gold.

'It is safe,' Balthazar told him. 'Hidden in the bottom of this grain

bag.'

'Good. And the perfume?'

'With our regular supplies. No one would steal that.'

Melchior chuckled. 'If they did, we could smell out the culprits quickly

enough!'

And then Balthazar said, 'There is gaming tonight, near the well.'

'I know,' Gaspar replied. 'But it is not for us.'

The fat man held out his hands in a gesture of innocence. 'We could but

look,' he said.

And Gaspar reluctantly agreed. 'Very well.'

Later, when the lire had been kindled and the people of Ziza came forth

from their tents to mingle, the three travellers joined them. Almost at once

Gaspar was sought out by a village elder, a man with wrinkled skin and rotting

teeth. 'I am Dibon,' he said, choosing a seat next to Gaspar. 'Do you come from

the east?'

'Yes, from Persia.'

'A long journey. What brings you this far?'

Gaspar did not wish to answer. Instead, he motioned towards a group of men

with small smooth stones before them. 'What manner of sport is this?'

'It is learned from the Egyptians, as are most things sinful.' Then the

old man leaned closer, and Gaspar could smell the foul odour of his breath.

'Some say you are a magus.'

'I have studied the teachings of Zoroaster, as have my companions. In

truth some would consider me a magus.'

'Then you journey in search of Mazda?'

'In search of truth,' Gaspar replied.

Then he felt the presence of someone towering over him, and saw it was the

figure of Nevar. His right hand rested on the sword at his waist. 'I would have

words with you, Gaspar.'

'What troubles you?'

'My only daughter Thantia, a virgin not yet twenty, tells me you gave her

a gold coin today.'

'Only because I feared the broken water jug was my fault.'

'No stranger approaches Thantia! You will leave Ziza this night!'

'We leave in the morning,' Gaspar said quietly.

Nevar drew his sword, and Gaspar waited no longer. He flung himself at the

big man and they tumbled towards the fire as the game-players scattered. Gaspar

pulled Nevar's sword from his grip.

Then Thantia broke from the crowd, running to her father.

'This stranger did me no harm!' she cried out.

'Silence, daughter!' Nevar reached for a piece of burning firewood and

hurled it at Gaspar, but it went wide of its mark and landed on a low straw

roof nearby.

'The stable!' someone shouted, and Gaspar saw it was the herdsman Ramoth

hurrying to rescue the horses. The others helped to quench the flames with

water from the well, but not before a quantity of feed and supplies had been

destroyed.

Then Gaspar and Melchior went in search of fat Balthazar, who had disappeared

during the commotion. They found him behind the row of tents, playing the

Egyptian stone game with a half dozen desert riders. He had a small pile of

gold coins before him.

'This must cease!' Gaspar commanded.

The nomads ran at his words, and Balthazar struggled to his feet. 'It was

merely a game.'

'Our task is far more important than mere gaming,' Gaspar reminded him,

and the fat man looked sheepish. 'While you idled I was near killed by the

swordsman Nevar.'

'A trouble-maker,' Balthazar agreed. 'I will not rest easy until Ziza is

behind us on our journey.'

Then as they passed the burned stable on the way to their tent, old Dibon

approached them saying, 'This ruin is your fault, Gaspar. Yours and Nevar's.'

'That is true, old man. We will stay here tomorrow and help rebuild the

stable.'

Dibon bowed his head. 'A generous offer. We thank you.'

But when they were alone, Balthazar complained, 'This will delay us an

entire day!'