Crossing the Borders of Time (6 page)

With the promulgation of the Nuremburg Laws in 1935 and their strict delineation of contacts permitted between Germans and Jews—including a ban on Jews hiring Aryan domestic employees under the age of forty-five—Fräulein Elfriede quit the household. It was a wonderfully unexpected result of the new Nazi rules. On the day that she left, the three children sat on the staircase as the hated young woman descended, each beating a metal pot with a big wooden spoon—a primitive drumroll to herald their freedom. Down the steps that wound to the street like a conch shell, the governess brushed past their knees with the sangfroid of a ramrod: her lips were clamped shut and she said not a word.

Much later, however, after the war, they heard from Fräulein Elfriede again when she wrote Alice in New York imploring her Jewish former employer to send her clothing and food. But in an uncharacteristic act of defiance, Hanna (Janine, by then) insisted that Alice ignore these entreaties. In her memories of girlhood, Fräulein Elfriede would ever loom large, wielding absolute power, like an advance guard of the Gestapo and the insidious emblem of the Reich’s creeping evil. “I’ll never come see you again,” Janine vowed to her mother, shocking them both with her threat, “if you send that cruel Nazi witch as much as a toothpick.”

Janine destroyed Elfriede’s letter, but Alice’s trove of long-preserved papers contains several from another former domestic employee, Agathe Mutterer, who used to come to the Poststrasse house to iron the laundry. She was seventy-four years old in 1961 when she obtained the Günzburgers’ New York address and, after an absence of twenty-three years, wrote from Freiburg:

Many difficult years have passed since our life together on the Poststrasse. How I used to love to come to you in celebration of ironing, when your three darling children made a ring around my ironing board, played the accordion for me, and brought me little chocolates to eat! I felt so at home in your dear family.

Since then, there has been much suffering, we have grown old, and almost all the relatives are gone. But I would be so happy if I could hear from you and know that you still are alive. Be happy that someone in the old homeland is still thinking of you with gratitude. May God always protect you.

In 1936, the same Agathe Mutterer had inscribed in Hanna’s childhood autograph book a message that would later prove amazingly prescient: “

My very good, dear Hannele

,” she wrote. “

Learn to carry your suffering patiently. Learn to be understanding and learn to forgive. Learn to love, and it will help you

.”

THREE

DIE NAZI-ZEIT

I

T WAS EARLY SPRINGTIME

1933 in the Black Forest Valley, and a mantle of snow still collared the mountains. In Freiburg, fragrant March violets crept on schedule out of the earth, and cone-shaped blossoms of pink and cream dressed the chestnut trees. But even in this university town in the balmiest corner of Germany, the simple joys of awakening spring would soon be eclipsed by a thunderous new political storm. This was the start of the

Nazi-Zeit

, the Nazi Time, as Germans now refer to the period, as if it arose like any other natural season.

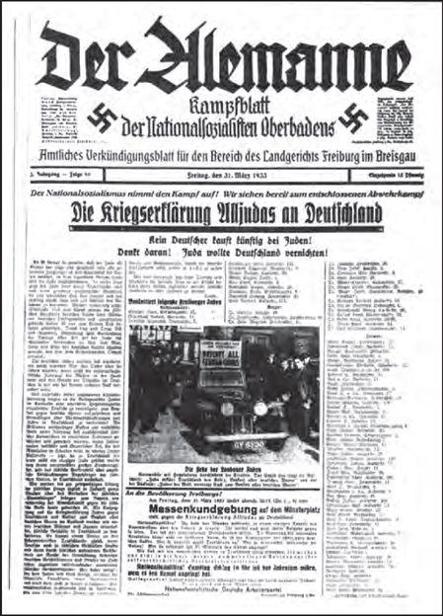

On March 31, Sigmar was stunned to discover himself immediately and directly affected by a headline that blasted across the top of Baden’s Nazi Party newspaper,

Der Alemanne

, trumpeting a war against Germany’s Jews as well as a boycott of all Jewish-owned firms.

ACHTUNG

!

BOYKOTT

! it read, naming scores of Freiburg businesses that Germans were exhorted to shun, beginning the following morning, by order of Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s

Reichsminister

and head of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, himself a former Freiburg student. The list included the Gebrüder Günzburger. “Jews want to destroy Germany!” the newspaper warned, announcing the nationwide boycott with a barrage of exclamation points. “In the future, no German should buy from the Jews!”

Printed in Fraktur, the gothic font widely used by the Nazis until they abruptly banned it in 1941 when Hitler deemed it outmoded, the paper urged the citizenry to rally that evening at eight fifteen at the Münsterplatz, the splendid square of the city’s cathedral. Here, at the market set up around the cathedral each morning, generations of burghers had gathered to haggle with weatherworn peasants over baskets and pushcarts filled with products and produce, richly arrayed under bright striped umbrellas. That night, however, in place of fruits and flowers, sausages and cheeses, olives and noodles, black-and-red Nazi banners emblazoned with swastikas dominated the cobblestoned square, as citizens amassed to shout new battle cries at their old Jewish neighbors.

On March 31, 1933, the front page of the Nazi Party newspaper in Baden

, Der Alemanne,

declared war against Germany’s Jews and announced a boycott of all Jewish-owned firms

.

(photo credit 3.1)

“Hitler has taken the rudder,” Hanna recalled hearing Sigmar bemoan to his brother Heinrich just eight weeks before, on January 30, when the Nazi leader maneuvered to seize power as chancellor. She had puzzled over her father’s metaphor then, but shortly after ten in the morning on April 1, Sigmar’s reasons for worry grew clear, as brown-shirted Nazi storm troopers formed a sidewalk phalanx outside his office. A curious crowd gathered to watch as they daubed the windows with crude yellow Stars of David to brand the business as Jewish and therefore off-limits.

Freiburg’s market on the Münsterplatz: the late-Gothic building on the left, with arches, is the red-colored Historische Kaufhaus (Historical Merchants’ Hall)

.

(photo credit 3.2)

It was Hitler’s stated objective to protect the purity of German blood through the elimination of Jewish “pollution,” and economic restrictions marked his first step. Though Sigmar, Alice, and their assimilated peers took care to present themselves always as true

Germans

of Jewish faith—any difference of identity a matter of religion, not race—Nazi dogma expressly outlawed that view. As a result, German Jews now anxiously redoubled efforts to distance themselves from the alien presence of

Ostjuden

rushing over their borders from Poland’s poor ghettos, those Orthodox Jews who attracted embarrassing public attention with their raven black clothes, beards, mangled German, and fringes.

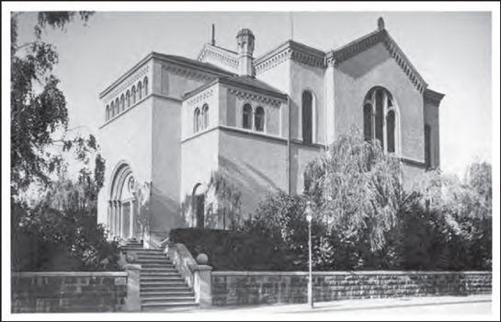

By contrast, Freiburg’s main synagogue, an imposing stone structure near the university, was a liberal one where, even in prayer, most men eschewed traditional skullcaps or yarmulkes and instead covered their heads with the same dark fedoras they wore on the street. Religion had a place in their lives, but within the greater community they were secularized. Hence Sigmar, like his non-Jewish counterparts, spent Saturday mornings at work in his office, and though he did not permit his wife and children to write, sew, or play on the Sabbath, he magnanimously awarded himself dispensation to continue smoking his favored cigars. “God forgives

Sigmärle

,” he would say with a shrug and a grin, by way of explaining his happy personal compromise with the Almighty.

He hewed more carefully to what the community expected of him just days after Freiburg’s first Nazi rally, when, despite the ire aimed at Jews, he persisted in having Hanna deliver paper-wrapped packets of Passover matzo to each of his best Gentile customers as a neighborly gesture. Hanna loved the eight-day holiday and its special breakfasts of

Matzekaffee

—matzo soaked in large cups of coffee, sugar, and milk—yet she dreaded her annual springtime chore.

“

Guten Tag

,” she would say as instructed, bobbing a curtsy with practiced politeness as she reluctantly made her visits through town. “I am the daughter of Sigmar Günzburger, and he would like you to have with his compliments a sample of our Passover matzo.”

Popular German folk wisdom had held that matzo worked to help ward off lightning, so it became traditional for Jews in some parts of the country to have their children bring the unleavened bread to non-Jewish neighbors at Passover time. New Nazi efforts to fan public outrage over the medieval “blood libel” charge failed to grant Hanna reprieve from her rounds. Indeed, she was obliged to make her deliveries again the following year, even as the lurid anti-Semitic propaganda vehicle,

Der Stürmer

, published a fourteen-page issue devoted to the Jews’ alleged ritual murder of Christian children in order to use their blood to make matzo.

Coinciding with Easter, however, Passover gave Hanna and Trudi the pleasure of a new dress, coat, hat, and shoes for public display. After each shopping trip with Alice for this purpose, the girls looked forward to showing their father their new finery, knowing ahead of time exactly how he would tease them. “Oh, but I already know all about it,” Sigmar would say with an air of great wisdom acquired from the rumor mill on the town’s busy square. “Everyone’s been talking about it on the Rotteckplatz!” And when the day itself finally came to parade their new things and they appeared dressed for synagogue, Sigmar would thump the heavy mahogany table that sat in the foyer and then clasp his hand to his chest as if overcome by the sheer delight and surprise of their beauty.

“

Was werden da die Leute sagen?

” What will the people say when they see you? he would ask in wonder, a rhetorical query that always elicited blushes and laughter. The joy of this moment was tempered, however, by having to stand next to their mother as she turned aside all compliments about their appearance.

“

Ach

, they’re nothing so special,” Alice would say with a dismissive wave of her hand that was meant to be self-effacing, when acquaintances stopped her to comment on the charm of her daughters in their matching ensembles—always light blue to enhance Hanna’s eyes, always red for her copper-haired sister.

Hanna, Trudi, and Norbert studied Hebrew in after-school classes, and on Friday nights they sang in the synagogue choir. At services, where women and girls were relegated to the balcony, Hanna’s thoughts wandered in spite of her will toward pure-minded devotion. A child who was acutely aware of the sudden potential for danger and loss and who groped in lonely spaces for the comfort of love, she believed in prayer as a kind of insurance. In the austere sanctuary, she struggled to find the smiling embrace of a benevolent God who might forgive a child’s secret doubts. Instead, she encountered a God who terrified her with thoughts of how she would pay for the sin of ignoring His Law, with its intricate rules and stern retribution. The reign of God in her world mirrored the authoritarian rule she knew in her home, and the probability of displeasing God or Sigmar engendered not only fear but also a smoldering sense of guilt that was already a driving part of her nature.