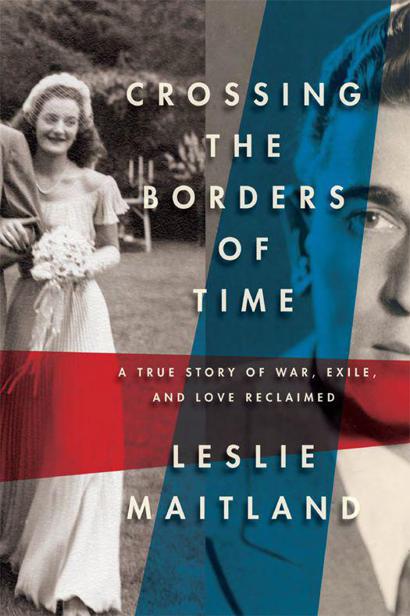

Crossing the Borders of Time

Copyright © 2012 Leslie Maitland

Production Editor:

Yvonne E. Cárdenas

Maps on

this page

and

this page

by Valerie M. Sebestyen.

Lyrics from “J’attendrai” by Louis Potérat, 1938.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site:

www.otherpress.com

.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Maitland, Leslie.

Crossing the borders of time : a true story of war, exile, and love reclaimed / Leslie Maitland.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-497-9

1. World War, 1939–1945—Refugees—France—Biography. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Jews—France—Biography. 3. Jewish refugees—United States—Biography. 4. First loves—France— Biography. I. Title.

D809.F7M35 2011

940.53′145092341073—dc23

2011047110

Disclaimer: The events described in this book are true. The names of a limited number of nonpublic individuals have been changed to protect their privacy and that of their families.

v3.1

For my mother, and for my father

O lost, and by the wind grieved,

ghost, come back again.

—T

HOMAS

W

OLFE

,

Look Homeward, Angel

CONTENTS

Map of the Günzburgers’ Route of Escape through Occupied France, 1940–1942

ONE

• “What’s Past Is Prologue”

FOUR

• The Sidewalk of Cuckolds

FOURTEEN

• Darkness on the Face of the Deep

EIGHTEEN

• The Lion and Miss America

TWENTY

• From the Dyckman House to Our New House

TWENTY-FOUR

• Crossing the Border

THE GÜNZBURGERS’ ROUTE OF ESCAPE

THROUGH OCCUPIED FRANCE,

1940–1942

ONE

“WHAT’S PAST IS PROLOGUE”

D

URING THE FALL

that my father was dying, I went back to Europe and found myself seeking my mother’s lost love. I say

I went back

almost as if the world my mother had fled and the dream she abandoned had also been mine, because I had grown to share the myth of her life. Perhaps it is common for children whose parents survived the Nazi regime to identify with them, to assume a duty to make their lives better. As my mother’s handmaiden and avid disciple in an oral tradition, I felt possessed by a history never my own. Still, not as yoked as she was to life’s compromises, I would prove more prepared to retrace the past and use it to forge a new future for her.

Time was running out on the present, and while my father grew weak in a lonely cave of silent bravado, it pained me to realize he would not even leave us the words that we needed. No deathbed regrets, explanations, or tears. An emotional bandit, he would soon slip away under shadow of night, wearing his boots and his mask.

When work as a journalist compelled me to leave New York for a week that October, I was anguished to lose precious time at Dad’s side. Yet how fast he would fade I failed to imagine. Nor could I foresee the course of my journey: that an impetuous detour to France from reporting in Germany would send me in search of Roland Arcieri—the man my mother had loved and lost and mourned all her life. Dreading my father’s imminent death and the void he would leave, I took a blind leap of faith into the past, dragging my mother behind me.

This is how one Sunday morning in 1990 I came to be visiting Mulhouse, a provincial French city just twelve miles from Germany’s Rhine River border. With cousins in town, I had visited Mulhouse twice years before. But on this crisp autumn day I was drawn toward a new destination: a fourteen-story, concrete and blue brick building whose boxy design represented what passed too often for modern in Europe. Although there was nothing about this unexceptional structure on a street densely shaded by chestnut trees to attract an American tourist, I instantly sensed that this was the place I needed to find. I stood at the spot—the X on a map to a treasure buried by time—torn by contradictory feelings. I ran a very real risk of discovering something better left hidden, yet I could not understand or forgive my failure to look here before.

An ache of remorse for all the lost years mingled with nervous excitement. Just up the stairs, I would finally learn what I had always wanted to know. Who was Roland? Where was Roland? What had happened to him in the near fifty years since the cruelties of war had stolen the girl he wanted to marry? I yearned to find my mother’s grand passion. Love for the dark-eyed Frenchman, whose picture she always kept tucked in her wallet, continued to pulse in her memory, the heartbeat that kept her alive. Now, at long last, I had tracked down his sister, who lived in this building, and I’d called her the previous evening.

“

Vous êtes la fille de Janine?

” You’re Janine’s daughter? “What Janine?” She dwelled on the name, then firmly declared she knew no Janine who had once been a friend of her brother’s. All the same, moments later, she surprised me by saying she preferred not to talk on the phone, but insisted that I come to see her. Her invitation seemed a curious one, and it made me uneasy.

Inside the building that Sunday morning, the lobby was empty and silent, its only adornment some scrawny dracaenas moping in pots in the corners. On a wall near the entry, a directory of twenty-eight tenants included the family name I remembered. Had she ever married, I might not have found her. Yet Emilienne Arcieri, Roland’s sister, was listed on the third floor, and a small elevator stood vacant and waiting. What would I say when I met her? How to explain my intentions in coming? Buying time to evaluate answers, I turned away from the elevator and slowly mounted the stairs.

Just a few flights above lay a glimpse of a road that my mother wished she had chosen. Blocked at the time by landslides of war, it had twisted throughout a lifetime of dreams while she went in another direction. With its pitfalls concealed, too late to turn back, it seemed cruel and ill-timed to make her confront where the path she had lost might have led her. Was that the gift I would bring her from France at this uniquely terrible moment? It was never a thing she had looked for or asked for, and I had kept my mission in Mulhouse a secret. I felt guilty about this radical shift from our faithful pattern of talking and sharing, but I knew she would try to dissuade me.