Crude World (16 page)

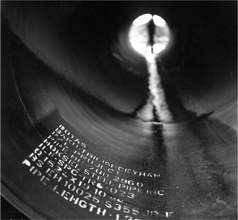

A section of the Baku-Ceyhan oil pipeline

If you walked past Frank Ruddy on a street in Washington, D.C., you wouldn’t look twice. Just another silver-haired lawyer with framed degrees on his office walls, you’d think. Ruddy graduated from College of the Holy Cross in 1959, then got a law degree from NYU and a PhD from Cambridge University. From 1974 to 1981 he was a top lawyer in Exxon’s legal department, and after that he joined the Reagan administration, becoming ambassador to Equatorial Guinea. Ruddy was a loyal insider of both the oil industry and the American government. Then he got whacked in the side of the head by a thing called reality.

In most countries, an ambassador is insulated from day-to-day life by a large staff that caters to his needs, by unenlightening contacts with government officials who tell him sweet nothings, and by the expectation that he will hew to whatever line the State Department has established. The opportunity and need for independent thought are not great. But in Equatorial Guinea Ruddy headed the tiniest of embassies,

the ministers he met were thinly disguised thugs who could barely read (some were thought to be functionally illiterate), and the country was considered so unworthy of a superpower’s attention (this was before oil was discovered) that nobody in Washington cared what Ruddy did or said. He was on his own.

After serving in Equatorial Guinea for four years he returned to Washington to become general counsel in the Department of Energy, and when the time came to move on from that job, he decided to practice law on his own. He was on track for a snoozy finish to a quiet career when Equatorial Guinea reentered his life. After oil was found, Ruddy realized from afar that Equatorial Guinea had become a worse hell house than before, because Obiang’s theft and repression had only increased. Initially, he watched in quiet dismay as Exxon and other companies, supported by the U.S. government, filled Obiang’s pockets with hundreds of millions of dollars in oil revenues. Then he began to speak out publicly, becoming one of the regime’s harshest critics as well as a skeptic about the corporate way of dealing with the world.

“I am not anti-capitalist, but capitalism can be its own worst enemy,” Ruddy told me when I visited the two-partner law firm that was his obscure (by Washington standards) place of business in 2004. His no-frills office was Dilbertian in its lack of pretense or luxury, with all the charm of a medical waiting room. “It causes things that are horrible and threaten to undermine it, like exploiting the poor. I know some people well in Exxon, and they will say, What can I do? I am a lawyer seventeen layers from the top. Others will say, It’s not our fault. We didn’t elect these sons of bitches. We’re just going to make money and get out.”

These excuses are truths, too. A midlevel lawyer or executive cannot change the priorities of a multinational whose survival depends on access to new oil fields. A corporation is akin to the Milgram authority figure who wears a white lab coat and calmly tells you to turn a knob. As a sweetener, money can be made by doing as you are told. Unlike Milgram’s subjects, who heard and saw the consequences of their actions, most executives do not come face-to-face with the poverty and violence their industry can foment; the closest most of them get to subsistence

misery is from the inside of an air-conditioned sedan that takes them from one meeting to another in a foreign city. They could connect the dots if they wished, but it’s easy and profitable not to do so.

“These aren’t stupid people,” Ruddy continued. “Evil is not people with mustaches who look like they’re doing bad things. Evil is done by people in suits sitting in boardrooms making horrible decisions. They do it because it’s worth it.”

Alain wore an impeccable suit, with a silk handkerchief tucked into his breast pocket in a dapper, just-so way. He was French, spoke a handful of languages and carried himself in an elegant manner, as though he had just emerged from the Élysée Palace or the pages of

Madame Bovary

. Alain was a senior executive at a West European oil company, and his elegant, drawl-free manner was the opposite of the slouching-toward-Riyadh gait of other oilmen. Alain had won multibillion-dollar contracts in the crucibles of oil, from the Middle East to Africa, so he knew the industry and enjoyed being known as knowing it.

We met for breakfast at a luxury hotel in Manhattan and talked about warfare, because the U.S. invasion of Iraq was on the horizon. Alain, who had been to Iraq many times and gave the impression of knowing Saddam Hussein, accurately predicted that Iraqis, though glad to be freed of Saddam, would resist an occupation. But he evoked the likelihood of an anti-American insurgency in passing, as though it would just be the

drôle de guerre

before the fiercest combat of all began, the one for Iraq’s oil.

For Alain, geology was nearly as sexy as sex itself. He excitedly talked up the physical wonders of Iraq, which has some of the largest reservoirs in the world, with high-quality oil close to the surface and easy to move to seaports. His awe was of the sort Frenchmen usually reserve for discussions about the beauty of the mistresses they possess or desire. Yet it was not just the loveliness of Iraq’s fields that moved Alain’s heart—it was the fact that exploration deals for fields of any promise, let alone great ones like those in Iraq, were rare and getting rarer.

“Iraq has everything,” he said. “It is a must for oil companies to go into Iraq because access to crude is the essence of an oil company. Without oil, what is their purpose?”

Executives like Alain, responsible for winning exploration and production contracts, are the gladiators upon whom oil firms depend for survival. In his voice I heard the pride of a man who’d survived the all-or-nothing combat that takes place in the offices, palaces and bars that are oil’s coliseums. He described the process as a “battle of giants” and a “fight to the death,” because small firms are crushed by larger ones in today’s world. As in ancient Rome, if you finish second you are dead. “It’s a natural war, below the belt,” Alain added with a smile.

He had just raised an issue I was curious about. With the stakes so high, is there anything an oil executive will not do?

Alain was a classic raconteur. A listener savored his words, despite trusting only half of them. He was evasive when discussing the shortcuts his cohorts were known to take. In recent years, executives from his firm had been convicted of bribe making, bribe taking and a multitude of other financial crimes related to illegal dealings in the Middle East, Africa and Europe itself. Some of Alain’s friends were felons. But at the mention of corruption, he expressed the despair of the maligned.

“Even my family and friends think that when I go to Saudi Arabia, I am carrying suitcases of cash to bribe everyone,” he said.

I didn’t need to ask if his family was right. His expression, of the “How could they think that?” variety, invited no follow-ups on the contents of his Mideast valise. I took a shortcut of my own, mentioning that American executives had said the French were the most corrupt. His eruption was so raw that crumbs of the croissant he was eating began shooting across the table.

“That’s bullshit. Do you think ExxonMobil acts like a saint in Nigeria? And Marathon in Gabon? You think they are saints? Bullshit. Look at the corruption scandals you have had, like Enron. Do you think these things do not happen in your oil companies, too? You have men like this in ExxonMobil right now.”

He was so mad that he forgot to proclaim his innocence. After

breakfast, one of his aides, who was British, escorted me to the street and listened as I innocently asked whether I should trust the French who said the Americans were the most corrupt or the Americans who said the French were the worst.

“You must check everything,” she advised softly.

On an April morning in 2006, I visited the federal courthouse in Manhattan. After giving my cell phone and digital recorder to a security guard, I rode an elevator to the eleventh floor. There, sitting on a hallway bench, was a distinguished-looking man wearing a pin-striped suit with a white handkerchief tucked into the breast pocket. On his right were two lawyers from Cooley Godward Kronish, a firm that specialized in white-collar crime. Seated on his left were two more people from Cooley Godward. The meter was running on this legal team, probably $2,000 an hour in all, but the well-dressed client could afford to wait.

I introduced myself. There was a brief silence.

“Are you looking into the relationship between the industry and the government?” the wealthy client asked.

“To the extent that I can,” I replied.

“That’s where to look,” he said, then smiled.

James Giffen was the son of a California clothier and had come a long way from his childhood in Stockton. His ambition had propelled him to a career in the steel industry, and this had sent him to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, when it was just becoming possible to do business with the former Evil Empire. Giffen did not speak Russian, but he was a schmoozer of the highest order, capable of ingratiating himself with powerful men by boasting persuasively about accomplishments and clout that did not always accord with reality. He even managed to befriend Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet leader, and put together a consortium of American firms that offered to make the largest investment in the Soviet Union since the time of Lenin. That deal fell through, largely because the Soviet Union itself was falling through, but Giffen did not disappear. He emerged as the top financial adviser to Nursultan Nazarbayev, leader of newly independent Kazakhstan.

In those days, American and European firms were brawling like roughnecks over contracts to explore Kazakhstan’s reservoirs, including the world’s sixth-largest field, Tengiz. Developing these fields would cost scores of billions of dollars, and the payoff would be glorious—Kazakhstan’s oil and gas could be worth more than $1 trillion. Giffen was custom-made for these above-the-law, fortune-making times. He was intelligent and aggressive as well as profane, hard-drinking and, when the situation required it, nasty. Giffen convinced Nazarbayev that foreign oil companies were predators—and this was certainly true, because the behemoths from Houston, London and Paris knew that a just-born country like Kazakhstan was an excellent locale for a financial killing. Giffen, who became so close to Nazarbayev that they shared saunas as well as confidences, was the regime’s pin-striped bulldog.

As deals were struck, Giffen’s wealth soared. An appreciative Chevron, which won the contract to develop Tengiz, agreed to pay him 7.5 cents for every barrel extracted—a “success fee” worth tens of millions of dollars. Giffen was delighted to show off his new wealth. In New York, he bought a posh estate in the suburb of Mamaroneck and drove into the city in an $80,000 Bentley. The walls of his Park Avenue office were decorated with pictures of himself and Gorbachev, President George H. W. Bush, President Carter, President Ford, President Nixon and so on. The glory days lasted until 2003, when Giffen was arrested at John F. Kennedy International Airport as he was departing for Kazakhstan.

According to the Justice Department’s indictment, Giffen had siphoned off nearly $80 million in payments from oil companies and distributed the proceeds to President Nazarbayev and Nurlan Balgimbayev, a former prime minister. Most of the funds were channeled through Swiss accounts and front companies. Some were conveyed in gifts, including $30,000 in fur coats, two snowmobiles and a luxury speedboat. Remarkably, the corruption indictment described President Nazarbayev not as a victim but as a partner in these crimes. The Kazakh leader was named as an unindicted coconspirator in a scheme to steal the country’s oil revenues.

I saw Giffen several times at the courthouse and visited him at his Manhattan office. (He had no trouble making his $10 million bail.) He was always impeccably dressed and reminded me, with his well-groomed hair and his prosperous look and abundant vitriol, of Lou Dobbs, the never-at-a-loss-for-outrage host on CNN. At his office, Giffen went on for nearly two hours about deal making in the Caspian, scribbling charts on a legal pad to illustrate one of his points: that an honest man willing to make a fair deal is unknown in the oil world. A condition of our meeting was that I not quote him, and that’s just as well, because profanities were among his closest verbal friends. His kindest description of oil executives was along the lines of “They want to fuck you against a wall.” He suggested that I burn into my head the notion that oilmen will do anything to win. Giffen, who was honest enough not to exclude himself from their anything-goes ranks, helpfully directed my attention to a notorious scene in the movie

Syriana

. An oilman, played by Tim Blake Nelson, explains how the system works: “Corruption is our protection. Corruption keeps us safe and warm. Corruption is why you and I are prancing around in here instead of fighting over scraps of meat out in the street. Corruption is why we win.” Giffen proudly reminded me that Nelson’s character was based on him.

In court, Giffen’s defense was startling. He did not contest the financial crimes of which he was accused. Instead, his lawyers asserted that he was, in addition to being the Kazakh leader’s close friend, top adviser and partner in saunas, an operative of the Central Intelligence Agency. And it was true—Giffen’s contacts with the CIA and other U.S. government agencies were not disputed by the agencies or the prosecutors who filed charges against him. His lawyers were offering what’s known as a “public authority defense,” which means that an accused’s actions were committed with the approval of the U.S. government and thus cannot be prosecuted. Giffen was our man in Astana. Giffen’s lawyers asserted that the U.S. government was in a position to know about the diversion of Kazakh revenues into the president’s pockets.