Cuba 15 (15 page)

25

Mom picked me up. “Isn’t it a little early?” she asked. “I wasn’t expecting your call so soon. It’s not even the witching hour yet.”

I didn’t say anything. I thought I might explode.

Our house was silent as a tomb when we returned. Dad, still on the early shift, was already in bed; Mark was off at a friend’s watching scary movies. Feeling like the un-dead myself, I unsnapped my ski boots at the door.

Mom scurried into the kitchen and plopped down at the table, where her notebook lay open. I must have called her away from her doodling.

“More restaurant ideas?” I asked. “Lay ’em on me.”

“Hmmm? Oh, I’m just looking over the community college catalog, making some notes.”

Due to my mood, I didn’t recognize this as the giant red flag that it was.

I tossed my sombrero on the Death Throne in the corner and got the milk and chocolate syrup from the fridge to make hot chocolate. I needed some comfort food.

Mom looked up from her work. She knew my life had just fallen apart in some unexplained manner, but she didn’t press me about it. “Why don’t you let me finish the hot chocolate for you, Vi, hon? Go on upstairs and change. There’s a surprise from your grandmother on your bed.”

With my boots off, I flew upstairs to my bedroom and shut the door. Having waited for this moment all day, I was ready to cry in the privacy of my own room. A few sobs rose, only to be swallowed when I saw Abuela’s gift on my pillow. Quickly I stepped out of my grass skirt and peeled off my tights, slipped into a pair of sweatpants, and went to investigate.

On my powder-blue pillowcase perched a jeweled tiara, like the ones I’d scoffed at in my

quince

book. But this wasn’t some Miss America–type rhinestone crown. This headpiece was elegantly simple, a hammered silver ring beaded with tiny freshwater pearls, silvery pink nuggets that looked good enough to eat. And though the metal was highly polished, the piece looked old—antique. It must have belonged to Abuela. Given to her, maybe, by her grandmother. The small card next to it read, TO VIOLETA IN HONOR OF YOUR FIFTEEN YEARS. LOVE, ABUELA. Reverently, I reached for the tiara and placed it on my head.

As I turned to catch my reflection in the round mirror over my dresser, I started. Frankenstein meets Tiffany’s! That would have been a better costume, I thought wryly. I ran downstairs to show Mom, just as the doorbell rang.

“Can you get that?” Mom called from the kitchen. “The candy is in the bowl on the floor.”

I grabbed the bowl and answered the door.

“Trick or treat!” came the unison threat.

The visitors stared at my alien princess getup, and I gaped back at them.

There, on the porch, dressed as both man and woman, stood Leda Lundquist. And beside her, Janell.

My

damas

wrestled me upstairs and into my room without further ado. Janell, strong as a kick-boxing ox, pulled one arm; Leda, bony knuckles indenting my other wrist, pushed. It felt like I was being hustled by the Mob to a waiting black sedan. The

quinceañero

book hadn’t said anything about possible abuse of power by

damas

.

“Why don’t you guys just leave me alone?” I whined as Janell sat me forcefully down at my desk.

“Oh,” said Leda, shutting the door. “So you can just, like, not deal with us?”

“You guys are being real jerks!”

“Oh, shut up, Violet. You sound like my dad, blaming everybody else.” Janell took a seat on my bed and looked me in the eye through her half mask. “You’re being the idiot, and you are going to talk to us and tell us what we want to know. Then, if you want, we’ll leave.”

Leda wordlessly reinforced the threat, her back to the closed door.

I couldn’t believe this. After all the incredible crap today, my two ex-best friends—neither of whom I wanted to see at this particular juncture—were ganging up on me. In the last twelve hours I had lost a tournament, a maybe-possible boyfriend, and two best friends, who were about to add insult to injury. If I couldn’t count on them now, how could I count on them at my

quince

? Janell looked back at me, mouth stiff beneath her mask, waiting for an answer.

Leda guarded the door fiercely, eyebrows raised. “

Well?”

she challenged.

The sinking sadness in me went sour. Hmph. I didn’t have to answer to her—a fourteen-year-old, for one thing. And Janell . . .

I was about to give Janell a piece of my mind when I caught my reflection in the mirror again. My eyebrows clenched low, my lips punched up. Finger streaks marred my green Frankenstein makeup, and Abuela’s tiara sat roughly askew.

I looked ridiculous.

My shoulders started to shake. I squeezed my eyes shut, but the shakes still came. Then the tears, as I opened my eyes, and then the laughter.

The girls looked bewildered.

“Hey, are you crying?” asked Leda, coming closer.

“Or what? What’s the matter?” asked Janell with concern.

I was laughing too hard now to explain. I pointed at the mirror, my tiara.

They eyed each other, then me. And joined in.

When she could speak, Janell pointed at me and gasped, “Wh-what’re you? Princess Leia with a hangover?”

“HA!”

Leda shouted, followed by three rumbling shakes. Mom’s laugh was contagious.

“Did I hear somebody crack a joke?” The door opened and Mom walked in with a tray of steaming mugs. “Hot chocolate, anyone?”

We calmed down enough to take the drinks from her, giggles spurting on and off like an artery had opened. Mom left us alone, and I got up and went to my closet for a T-shirt.

“I’m boiling in this down vest,” I admitted. My green makeup had run from the sweat and tears, and I got some on my shirt in the switch, but what the hell. I righted my tiara and sat back down with my hot chocolate, next to my friends.

“Look, Violet,” Janell said. She had taken off her mask. “What happened to you today in my Verse round?”

I thought back to this afternoon and writhed. “Er, it was—that poem.”

“The Maya Angelou?”

“Yeah, the woman thing.”

Janell waited, but an answer was not forthcoming.

“And your problem would be . . .”

“It was too racy,” I blurted out.

“Racy?”

“Well, there were, like, body parts discussed.” I suddenly knew how Mark felt on the subject.

“She means sex was implied,” translated Leda.

“Well, for God’s sake, Violet!” Janell tossed up her hands, exasperated. “Doesn’t that go with the whole ‘woman’ thing?”

I couldn’t deny that.

“Yeah, Paz, maybe it’s your outlook that needs some work,” Leda added.

“Hey, it’s my outlook and I’ll stick with it. It’s just—I can’t help it, I’m embarrassed talking about that stuff. Or possibly standing onstage while someone else talks about it.”

“Maybe you just need to understand the poem better,” Janell suggested. “You didn’t even hear the whole thing.”

She was right. I could at least be fair.

“Okay,” I said. “Do it.”

Janell

was

right. The poem was perfect. Even though it was a little . . . candid.

The part at the beginning, where the poet says she’s not a fashion model; that’s true of most women. And later on, she tells about these men who go nuts over her “mystical” charms—they’re really going nuts over her, as a woman, just as she is. No mystery.

Janell reached the last stanza. “ ‘Now you understand / Just why my head’s not bowed. / I don’t shout or jump about / Or have to talk real loud. / When you see me passing, / It ought to make you proud.’ ”

I smiled, flashing on Dad.

“ ‘I say, / It’s in the click of my heels, / The bend of my hair, / The palm of my hand, / The need for my care. / ’Cause I’m a woman / Phenomenally.’ ”

“ ‘Phenomenal woman, / That’s me,’ ” we finished together.

“Awesome,” said Leda. “A feminist slant is exactly what this ritual needs.”

“It already has one,” I pointed out. “Remember? We threw tradition in the toilet and flushed hard.”

Janell hung an arm around me. “It’s going to be a great party,” she said, so sincerely that it brought a guilty taste to my mouth; I had been intent on replacing her as

dama

only a short while ago.

“There’s still one thing I’ve got to tell you, Abominable Woman,” I said, addressing Leda.

She took her cigar out of the breast pocket of her jacket and wiggled it at me, Groucho Marx–style. “Say the secret woid.”

“Stop messing with my man,” I said, snatching Leda’s cigar and thrusting the thing into my trash can.

“Hey!”

“Thank God,” Janell said. “That cigar has seen better days.”

“Aw, come on,” Leda protested. “All right, I’m sorry. I got a little carried away at the party, but I was not making a move of any sort on your man. I didn’t even know Clarence

was

your man.”

“Neither does he,” I confessed. “But tonight was supposed to be the night.”

“Then how come you weren’t over there, camping out on his lap?”

“I didn’t know who he was until he took off that mask!”

“What a messed-up night,” Janell said, finishing her hot chocolate.

Leda nodded. “I second the motion.”

We sat there for a minute.

“I don’t know,” I said, offering an apologetic smile. “It didn’t end up so bad.”

26

The next day, I phoned my aunt Luz in Portland.

“Hi, Tía? It’s me.”

“Hey, Violet, ¿qué te pasa? I haven’t heard from you in ages. I was just getting ready to call you.”

Tía Luci always makes me feel that way—like she’s just been thinking about me and I’ve read her mind. It occurred to me that Señora Flora had given me that same impression.

“How’re you doing, Tía? I miss you.”

“Good, kiddo. What’s up?”

“Oh, brother. You won’t believe the Halloween I had.”

“No me digas.”

I did say. I told her all of it, and how I’d almost lost both my

damas de honor

in one night.

“Oh, that’s bad,” Tía commiserated. “I knew a girl when I was growing up who lost her entire court to the German measles.”

“Well, I do have one problem. That’s why I’m calling.”

“Aha.”

“Señora Flora is having trouble finding a band that can play both ‘Guantanamera’ and ‘Sweet Home Chicago.’ ”

Tía Luci chuckled. “No blues

salseros

in your neighborhood?”

“Huh-uh. Do you have any ideas?”

“Sure. I’ll do the music.”

“You’re in a band?”

“No, I’ll DJ it. I used to have a radio show in college. I’ve got some smokin’ tapes.”

“Hey, that sounds great, Tía. Really?”

“It’ll be my gift to you,” she said. “I’ll start working on some new mixes right away.”

“Cool. And . . . another thing.”

“Shoot.”

“I’ve got this semester project coming up for Spanish, and Leda and me are doing it on Cuban music. But Dad gave us these really old-fashioned tapes that don’t have anything to do with today. We were wondering if maybe you know of some newer music? Something we can relate to?” Leda had begged me to ask. We’d checked the Web, but there were so many sites, we didn’t know where to start. And we were still waiting for books from the library.

“

¿Qué?

Chica,

you mean you haven’t heard of ¡Cubanismo!? Muñecas de Matanzas? Los Van Van?”

I had to say no.

“Ay, ay, ay,” she said, sorry for me. “I’ll FedEx you some tapes tomorrow.”

“Plus we need some info. And maybe the lyrics. We have to be able to write a report on this.”

A silence as she realized Dad was of no help. “I can jot down some notes, give you some references. So, you asked Alberto?”

“Dad said he only listened to rock and roll growing up. Didn’t you like the same stuff?”

“Oh, believe me, I did. But I grew up with Papi’s old records from the Golden Age too.”

“Dad said he was embarrassed by them.”

Luz sighed. “I guess I was lucky; I was still a little girl when we moved to Chicago from Miami. I was just one of the

muchachas

. Alberto was in junior high, though, and it wasn’t easy being the boy from Little Havana. The way some of the kids treated him, like he just got off the banana boat . . . I saw what that did to him. It was like he wanted to prove he was all apple pie.”

“So? What’s to stop him from listening to the new stuff now?”

She clucked her tongue. “You couldn’t even buy Cuban pop music in this country until a couple of years ago, thanks to the embargo. I found that out when I started going to Cuba rallies and listening to the Latino hour on public radio. . . . I felt like I’d been missing something. That music was in me. I just had to catch up.” She puffed a laugh. “So maybe Alberto will too, someday!”

“Maybe. I think what Dad needs is to make his

quince,

” I joked.

“Claro

que sí,”

said Tía.

Monday morning I found a note taped to my locker: HERE’S MY NUMBER.. CALL ME. CLARENCE

Why didn’t he just call

me

?

Probably because I was so gracious and witty the last time. I always kept them coming back for more. Still, he gave me his number.

Hoo boy. Now I had to call him. I carried the note around all day, arguing with myself that maybe a correspondence relationship might be enough.

Leda caught me rereading the note for the trillionth time on the bus home.

“What’s that?”

I refolded the tired creases. “Oh, nothing, really. Just a guy’s phone number . . .”

She snatched it away from me with an animal squeal. “You’re gonna call him.” She said this like it was a true fact already.

“Well, I don’t know, I—maybe I should wait for him to call me?”

She thrust Clarence’s note back in my face. “You are going to call him.” She said this like a threat.

“Okay, okay. I’ll call him when I get home.”

I scouted the house: Mom was still at the thrift store, Dad would be home pretty soon. Mark had let himself in after school and was in the backyard doing something absorbing with a shovel. I didn’t want to know.

I found Chucho asleep under the piano bench and brought him to the kitchen phone with me for moral support.

“Clarence?” I said when a male voice answered.

“Wait, I’ll get him.”

How many brothers did he have?

He answered. “Hello?”

“Hi, Clarence, it’s Violet.” I petted Chucho to stay calm; petting dogs is supposed to lower your blood pressure.

“God, Violet, hi! I wasn’t sure you’d call.”

That made two of us. “Well, you know, I might have won that publishers sweepstakes, or something.”

He laughed. “You could be a winner! No, sorry, not today. I just wanted to say I missed you the other night at the party.”

How could anyone have missed me? “You didn’t recognize me either?”

“I did, I was just waiting till the costume judging for the unmasking. Didn’t want to spoil the surprise.”

I recalled the identical Bullsmen. “Your brothers! How many brothers do you have, anyway?”

“There are seven of us. Thomas is married, Jasper’s in med school, Silas is stationed in Saudi, Dale works at O’Hare, Herbert and Richard are in community college, and I’m the youngest. Or shall we say, the freshest?”

“Well, I met one of your brothers at the party. Who won the costume contest, anyway?”

“Slade and Trish for Bonnie and Clyde.”

“Lame.”

“Yeah,” he agreed. “Well, look, Violet, I hope you’re not mad or anything.”

“Hey, it was a masquerade party,” I said, shrugging off the incident. He hadn’t given Leda his phone number.

“Good. I was hoping you might want to go out sometime?”

I realized I was petting Chucho with a vengeance; he squirmed and jumped off my lap.

“Sure,” I said.

“Great, I’ll let you know.”

I hung up, wondering, Did he just ask me on a date? But he hadn’t invited me anywhere; he’d asked for a rain check.

Great, I’ll let you know

. They were the most romantic words anyone had ever said to me.

So I forgot all about Tía Luci’s package, and sure enough, on Wednesday, right after my piano lesson, here came the deliverywoman. Funny, you always hope it’s for you when you see the truck parked on your street, but it never is. Now the one time I was actually expecting a special delivery, it slipped my mind, and I wasted all that good anticipation.

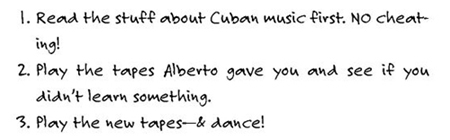

I accepted the envelope and opened it: two tapes and a bunch of photocopied notes and newspaper articles. And instructions from Tía:

I showed Dad, who had just walked in the kitchen door wearing his white pharmacist’s uniform over a pair of plaid slacks, with brown rubber-soled work shoes. Weariness tinted his usually animated face. The schedule had been getting the best of him lately. But he brightened a little on reading Tía’s note.

“Veo la luz,” he said, as he does when his sister, Luz, impresses him.

I see the light

. “She’s laid out the whole music history here,” he marveled, leafing through the assembled literature. “Can I have a look at it when you’re through?”

I nodded. “It’s fantastic. The project’ll practically write itself. So we won’t be needing your help after all, Dad.” I expected to see his eyes shine with relief, but disappointment filled them instead. “Until the end,” I added. “Would you read the final draft of our report?”

This mollified him, and he even whistled “Cielito Lindo” on his way upstairs.

I called Leda to come over, and we took turns reading to each other in my room. We followed Tía Luci’s directions explicitly, even the dancing. After all, no one was around. And what if Luz

could

read my mind?

“This stuff rocks,” Leda summed up when we got to the new music. “But they couldn’t have done it without the old rhythms.”

“What’s weird is how they banned Cuban music here along with everything else under the embargo. Tía told me you couldn’t buy these tapes until recently.” I pointed to one of the photocopies. “Because of this ‘trading with the enemy’ law.”

“Hey, that would be a great title for the project: ‘Jamming with the Enemy.’ ”

“Very

creativo,

” I said, nodding. “Let’s get started.”

“Are you kidding?” Leda said, pushing aside Tía’s notes. “That’s enough to show Señora Doble-U. We’ve got a whole month to go, dude. Let’s wait till the last minute.”