Cyclopedia (5 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

BINDA, Alfredo

Born:

Cittiglio, Italy, August 11, 1902

Cittiglio, Italy, August 11, 1902

Â

Died:

March 30, 1986

March 30, 1986

Â

Major wins:

World road title 1927, 1930, 1932; Giro d'Italia 1925, 1927â9, 1933, 41 stages; MilanâSan Remo 1929, 1931; Giro di Lombardia 1925â7, 1931

World road title 1927, 1930, 1932; Giro d'Italia 1925, 1927â9, 1933, 41 stages; MilanâSan Remo 1929, 1931; Giro di Lombardia 1925â7, 1931

Â

Nickname:

Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa

Â

One of the CAMPIONISSIMO, the first professional world champion, a great team manager, and the only man to be paid not to ride the Giro d'Italia, because he was so good that the organizers were worried he would kill off any interest in the race. By curious coincidence, he was

also the first man to be offered start money to ride the TOUR DE FRANCE.

also the first man to be offered start money to ride the TOUR DE FRANCE.

Binda began working life as a bricklayer and developed his sprinting speed with track racing when he was young. From 1927 to 1930 he was almost unbeatable, taking the inaugural professional world road race title on the Nürburgring in Germany ahead of the other

campionissimo

of the time, Costanta Girardengo. He won the Giro in 1925 and from 1927 to 1929, with 12 stage wins in the 1929 race, but was discreetly requested not to start the 1930 race and given the equivalent of first prize, six stage wins, and the bonus he would have won. “My best Giro,” he said later. “I consider I won it five and a half times.”

campionissimo

of the time, Costanta Girardengo. He won the Giro in 1925 and from 1927 to 1929, with 12 stage wins in the 1929 race, but was discreetly requested not to start the 1930 race and given the equivalent of first prize, six stage wins, and the bonus he would have won. “My best Giro,” he said later. “I consider I won it five and a half times.”

At that year's Tour de France, on the other hand, HENRI DESGRANGE badly needed him to lend some luster to the event, being run for the first time with national rather than trade teams. Binda was paid a daily rate, won two stages, and quit so he could prepare to win a second world title. He was sworn to silence over the feeâDesgrange had been adamant he would never pay start moneyâand the secret emerged only in 1980.

After retirement in 1936, Binda became Italian national team manager, with the task of keeping FAUSTO COPPI and GINO BARTALI from falling out when their rivalry was at its height. He led the elaborate negotiations to ensure the pair would ride the 1949 Tour under Italian colors, then was responsible for persuading Coppi to stay in the race after he crashed on the stage to Saint-Malo and became convinced he should quit. He also had to deal with little matters like his deputy (Coppi's trade team manager) failing to provide Bartali with a feed bag, and the fact that on the decisive day in the ALPS, neither would cooperate with the other.

Binda also oversaw Coppi's second Tour win, in 1952, and guided Italy to world titles with Coppi and Ercole Baldini in 1953 and 1958. Later, he ran a company that made shoes, which was best known for producing toestraps, the universal way of attaching cycling shoes to pedals until ski-type bindings became popular in the late 1980s.

Â

BMX

Bicycle motocross entered the mainstream in 2008 when it was part of the program at the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES. The hackles of traditionalists were raised, because the event it ousted, the kilometer time trial, was one of the classic disciplines. But the appeal was obvious. Run over short obstacle courses using scaled-down bikes, BMX is accessible, spectator friendly, and spectacular for television viewers. It's also indelibly imprinted in the minds of anyone who watched the science fiction film

E.T

. “It's a power sport that calls for skills and nerve as well,” says the British world champion Shanaze Reade. “You get a real rush of adrenaline when the start gate drops because you have only got 45 seconds to get everything out.”

Bicycle motocross entered the mainstream in 2008 when it was part of the program at the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES. The hackles of traditionalists were raised, because the event it ousted, the kilometer time trial, was one of the classic disciplines. But the appeal was obvious. Run over short obstacle courses using scaled-down bikes, BMX is accessible, spectator friendly, and spectacular for television viewers. It's also indelibly imprinted in the minds of anyone who watched the science fiction film

E.T

. “It's a power sport that calls for skills and nerve as well,” says the British world champion Shanaze Reade. “You get a real rush of adrenaline when the start gate drops because you have only got 45 seconds to get everything out.”

BMX began in the 1970s in California when kids used to mess around on dirt tracks, inspired by the skill and speed of motocross racers. Today, races consist of heats for up to eight riders over a short purpose-built course (300â400m) including banked curves (berms), humps, and jumps. The riders line up with their wheels against a start gate that drops to launch them down a start ramp. Usually this ramp is only a few meters high, but at the Olympic Games, to make it a livelier spectacle for television, riders flew down a vertiginous eight-meter-high ramp with a slope of 33 percent. That meant the riders hit the course at over 30 mph, enabling them to get up to five meters into the air over the jumps.

BIZARRE

BMX FACTOID

BMX FACTOID

Nicole Kidman had her first starring role in the 1983 film

BMX Bandits

in which she played a bouffant-haired, crime-fighting, BMX-riding teenager.

See FILMS for other two-wheeled movies

.

BMX Bandits

in which she played a bouffant-haired, crime-fighting, BMX-riding teenager.

See FILMS for other two-wheeled movies

.

4

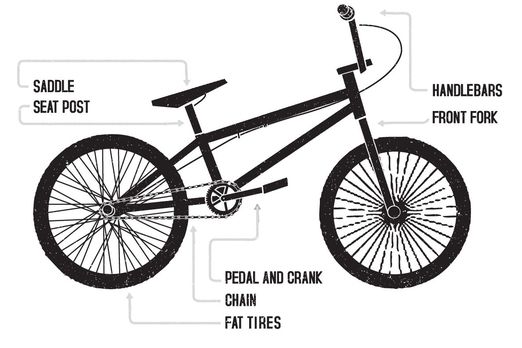

Crashing is an ever-present risk so the riders wear loose-fit clothing and full motorcycle-style helmets. Bikes are small-wheeledâ20 or 24 inchesâwith one brake and fat tires, and are small-framed with a huge amount of clearance between seat and saddle so that the riders can throw the bike about more easily.

Basic techniques include wheelies, bunnyhops, and manualingâwhen the rider lifts the front wheel of the bike over a jump with the back wheel still on the groundâas well as slide braking, in which the bike is pushed sideways around the corner, with the rider on the very edge of losing control. Contact is important as well, because on track the riders fight for position going into and out of the bends.

World championships have been held in BMX since 1982, while Freestyle BMXâdoing tricks on the bike along the lines of skateboarding or snowboardingâis a staple at the annual extreme sports X Games. But the sport really gained credibility when it became part of the Olympic program in 2008. To assist Reade in her build-up for gold, the GREAT BRITAIN team built her a course in Manchester that included an extremely steep Olympic standard start ramp. Unfortunately she crashed out when going for gold; the inaugural Olympic champions were Anne-Caroline Chausson,

a former MOUNTAIN-BIKE downhiller from France, and Maris Strombergs of Latvia.

a former MOUNTAIN-BIKE downhiller from France, and Maris Strombergs of Latvia.

Former BMX champions who have made it in other disciplines include: Robbie McEwen, Australian road sprinter who won the green jersey at the 2002 Tour de France; CHRIS HOY, Scottish track sprinter who took three gold medals at the 2008 Olympics; and Jamie Staff, BMX world champion who won Olympic gold on the track in 2008.

BOARDMAN, Chris

Born:

Hoylake, England, August 26, 1968

Hoylake, England, August 26, 1968

Â

Major wins:

Olympic pursuit gold 1992; Olympic time trial bronze 1996; world time trial gold 1994; world pursuit champion 1994, 1996; world hour records 1993, 1996; three stage wins in Tour de France; MBE 1992

Olympic pursuit gold 1992; Olympic time trial bronze 1996; world time trial gold 1994; world pursuit champion 1994, 1996; world hour records 1993, 1996; three stage wins in Tour de France; MBE 1992

Â

Further reading/viewing:

Chris Boardman, the Complete Book of Cycling

, Partridge Press, 2000; DVDs:

Battle of the Bikes; The Final Hour

Chris Boardman, the Complete Book of Cycling

, Partridge Press, 2000; DVDs:

Battle of the Bikes; The Final Hour

Â

The first British Olympic cycling gold medalist of the modern era and one of the men behind the sport's great revival in GREAT BRITAIN in the 21st century, Boardman is mildly dyslexic, with an investigative brain and amazing mind for detail. His interest in cycling stemmed purely from a love of competition rather than the act of riding a bike. “I'm not a cyclist,” he said. “I rode bikes. Ninety percent of me said âI don't believe I'm here,' 10 percent said I had to do it. I was a visitor, which was a shame because [cycling] is a lovely sport.”

Boardman began his career as a British TIME-TRIALLING championâwinning the 25-mile and hill-climb titlesâthen targeted the individual pursuit at the Barcelona Olympics, where his gold was the first by a British cyclist since 1920. To some extent, the feat was overshadowed by the fact that he won the pursuit on a radical aerodynamic bike with

a carbon-fiber monocoque frame made by Lotus and designed by MIKE BURROWS; Boardman won the race, but the bike grabbed the headlines.

a carbon-fiber monocoque frame made by Lotus and designed by MIKE BURROWS; Boardman won the race, but the bike grabbed the headlines.

While his time-trialling RIVALRY with GRAEME OBREE made news in Britain he and his trainer, Peter Keen, turned their attention to the HOUR RECORD, which he broke in 1993, earning a professional contract with the French team GAN. In his first Tour de France, in 1994, his time-trialling skill secured him the yellow jersey when he won the prologue time trial. He also took the opening stage in 1997 and 1998, but crashed out of the Tour four times in six starts.

In 1994 Boardman won the inaugural time trial world championship and in 1996 he won an Olympic bronze medal at the discipline, then set what is now the definitive distance at the hour with 56.375 km. After the rules governing the hour record were changed, he decided to end his career with an attempt under the new system and managed to beat EDDY MERCKX's 1972 distance of 49.431 km by a mere 10 m.

Boardman was unlucky to race at a time when DOPING was rampant; he found out late in his career that he suffered from a hormone deficiency that causes osteoporosis and that it could only be treated with injections of testosterone, a banned drug. Following the Festina doping scandal of 1998 the authorities did not feel they could let him use the drug, so he could only take up the treatment after retirement. He is perhaps the only cyclist to quit racing in order to use banned drugs.

Boardman and Keen had been highly inventive in their approach to training, using a treadmill to simulate mountain climbs and focusing on quality not volume. After a few years in retirement, Boardman went to work on the British Lottery-funded Olympic track racing program founded by Keen. When not devoting time to extreme scuba divingâhis personal obsessionâand his large family, Boardman mentored gold medalists such as BRADLEY WIGGINS, devised coach management systems, became one of the program's core management quartet, and was one of the “secret squirrels” who researched aerodynamic uniforms in the run-up to the Beijing Games of 2008.

Â

(SEE ALSO

AERODYNAMICS

,

GREAT BRITAIN

,

OLYMPIC GAMES

)

AERODYNAMICS

,

GREAT BRITAIN

,

OLYMPIC GAMES

)

Other books

Reasonable Doubt by Williams, Whitney Gracia

Stories in an Almost Classical Mode by Harold Brodkey

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Margolis, Jay

Emergence by Various

Mine to Take by Dara Joy

Home Planet: Apocalypse (Part 2) by T.J. Sedgwick

The Old Contemptibles by Grimes, Martha

Tantric Coconuts by Greg Kincaid

Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab by Shani Mootoo