Daily Life in Elizabethan England (19 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

1

Visitation of Mary

3

Translation of St. Martin

15

St.

Swithun

20

St.

Margaret

22

St.

Magdalene

25 St. James the Apostle

26

St. Anne

August

August began the hardest time of a husbandman’s year, with the harvest of the main crops. There was a great deal of work to be done in a short time, so the entire family was involved and temporary workers were often hired. The men went into the fields with sickles to harvest the grain. Then the harvested grain was bound into sheaves, often by the women and children. The sheaves were stacked and loaded onto carts to be taken away to shelter—as with the hay, it was essential to keep the grain dry lest it rot.

The stalks of grain were cut toward the top, leaving the rest of the stalk to be harvested later with a scythe to make straw.

1

Lammas

6

Transfiguration of Christ

7

Name of Jesus

10

St.

Laurence

Cycles of Time

87

Making hay while the sun shines. The man on the right has stripped to his shirt in the heat. [Hindley]

24 St. Bartholomew the Apostle

(

Bartholomewtide

)

28

St. Augustine of Hippo

29

The Beheading of St. John the Baptist

September

At the end of harvest, the harvesters celebrated

harvest home,

or

hockey.

The last sheaf of grain would be brought into the barn with great ceremony, and seed cake was distributed. After the harvest was done, and on rainy days when harvesting was impossible, the husbandman threshed and winnowed. Threshing involved beating the grain with flails so that the husk would crack open, allowing the seed to come out. Then it was winnowed: the winnowers waved straw fans, blowing away the straw

and the broken husks (called chaff). After harvest was over, the husbandman began work on the winter crop: the winter fields had to be plowed, and the husbandman would begin to sow rye. This was also the season for gathering fruit from the orchard.

1

St. Giles

7

St. Enurchus the Bishop

8

Nativity of Mary

(

Lady Day in Harvest

)

88

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

A GERMAN TRAVELER OBSERVES

A HARVEST HOME CELEBRATION

As we were returning to our inn, we happened to meet some country people celebrating their harvest-home; their last load of corn they crown with flowers, having besides an image richly dressed, by which, perhaps, they would signify Ceres; this they keep moving about, while men and women, man-and maidservants, riding through the streets in the cart, shout as loud as they can till they arrive at the barn.

Paul Hentzner,

Paul Hentzner’s Travels in England during the Reign of Queen Elizabeth

(London: Edward Jeffery, 1797), 55.

14

Holy Cross Day

(

Holy Rood Day

). This was traditionally a day for

nutting,

or gathering nuts in the woods.

1

7 St.

Lambert

21 St. Matthew the Apostle

26

St.

Cyprian

29 St. Michael the Archangel

(

Michaelmas

). This day marked the end of the agricultural year: all the harvests were in, and the annual accounts could be reckoned up. The day was often observed by eating a goose for dinner.

30

St.

Jerome

October

October was the time to sow wheat, which had to be done by the end of the month. The end of the wheat sowing was often marked by a feast.

1

St. Remigius

6

St. Faith

9

St. Dennis

13

Translation of St. Edward the Confessor

17

St. Ethelred

18 St. Luke the Evangelist

25

St.

Crispin

28 Sts. Simon and Jude the Apostles

31

All Saints’ Eve

November

The dairy season ended during this month, and the cattle were brought in from pasture and put in stalls for the winter. This was the time to slaugh-

Cycles of Time

89

ter excess pigs in preparation for the winter—surplus meat was made into sausages or pickled. As the weather began to become too cold for agricultural work, the farmer took time to cleanse the privies, carrying the muck out to the fields as fertilizer; he might also clean the chimney before the chill of winter set in.

1

All Saints

(

All Hallows, Hallowmas, Hallontide

)

2

All

Souls

6

St.

Leonard

11

St. Martin.

This day was traditionally associated with the slaughter of pigs for the winter.

13

St.

Brice

15

St.

Machutus

16

St. Edmund the Archbishop

17

Accession Day

(

Queen’s Day, Coronation Day, St. Hugh

). This was the only truly secular holiday: it commemorated Queen Elizabeth’s accession to the throne in 1558.

20

St. Edmund King and Martyr

22

St.

Cicely

23

St.

Clement

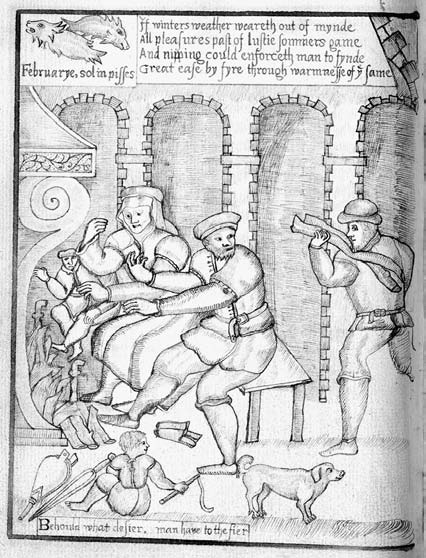

Warming up by the fire. [By

permission of the Folger

Shakespeare Library]

90

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

25

St.

Katharine

30 St. Andrew the Apostle

—The season of Advent began on the nearest Sunday to the feast of St.

Andrew (i.e., between November 27 and December 3). People were supposed to observe the same fast as in Lent, although few actually did.

December

This was one of the least demanding times of the husbandman’s year, and one of the principal seasons for merrymaking and sociability, especially around Christmas. This was a good time for splitting wood; otherwise, relatively little outdoors work was suitable for this month, so it was a good time to sit at home maintaining and repairing tools in preparation for the next year. The winter snows arrived sometime in December.

6

St. Nicholas

8

Conception of Mary

13

St. Lucy

21 St. Thomas the Apostle

25

Christmas.

Christmas, along with Easter and Whitsun, was one of the three most important holidays of the year. The Christmas season lasted from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day (January 6); it was a time for dancing, singing, gymnastic feats, indoor games (especially cards), and folk plays. People often chose a Christmas Lord, Prince, or King to preside over the festivities. Elizabethan Christmas rituals in many respects resembled some of the traditions still in use today. People decorated their homes with rosemary, bay, holly, ivy, and mistletoe (Christmas trees were introduced from Germany much later); and they enjoyed the richest food they could afford. Nuts were a traditional food for Christmas, in addition to festive pies and cakes and

brawn,

a type of pickled pork. Warmth and light were an important part of the Christmas festivities, observed in the burning of a Yule log and the lighting of many candles. Christmas Eve was a highly festive occasion when people often drank the wassail (see its description under January 1).

26 St. Stephen the Martyr

27 St. John the Evangelist

28 The Holy Innocents’ Day

(

Childermas

)

29

St. Thomas of Canterbury

31

St. Silvester the Bishop

5

Material Culture

WORK, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE ECONOMY

Work in Elizabethan England was more personal than it is today. There was less distinction between people’s work and their personal lives, or between work spaces and personal spaces. In many cases, employees were fed by their employer and often they lived in their employer’s house. Specialized working facilities akin to modern offices, commercial buildings, and factories were rare. Work and business tended to be conducted in or around the home. Merchants, craftsmen, and shopkeepers all worked in their houses; in the country, women labored at home while the men were out in the fields.

Agriculture

England in the late 16th century was still predominantly rural, so for most people, work meant farmwork. The production of food was a vital necessity, and very labor-intensive since hardly any machinery was involved. This meant that a substantial proportion of the population was engaged in the growing of staple foods, especially grains. Yet contrary to what is sometimes imagined, the Elizabethan rural economy was already market-oriented. A country household produced some goods for its own use, notably foodstuffs, but it was not self-sufficient: farming families supported themselves by producing a surplus for sale, rather than subsisting on their own produce.

92

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

There were two general modes of agriculture:

champion

(or open field) and

woodland.

In general, champion agriculture was most common in the central part of the country, woodland around the periphery.

In champion areas all the fields around the village were open, divided into a few huge shared fields that might be hundreds of acres each, with each large field surrounded by a tall and thick hedge that served as a fence to control livestock. A landholding villager had multiple plots, each of a few acres or less, scattered among the large fields—the scattering of the plots ensured that no villager was stuck with all the worst land.

In addition to the fields for raising grains, the village also had meadows to produce hay and pasturage for livestock. Each villager’s holding generally included meadows as well as fields and came with the right to pasture a stipulated number of oxen, horses, and sheep in the common pasture. There were also common rights over wastelands: forested areas were useful places for feeding pigs (they love acorns) and gathering firewood, and marshy lands could be used for pasturing livestock and gathering reeds. Administration of agricultural matters was handled by the manorial court.

The mode of life in woodland areas was more individualistic. There were no common lands, and each landholding was a compact unit separate from the others. Since there were no commons there was not the same need for the community to cooperate. Woodland areas were not actually wooded: each holding was bordered by its own hedges, which gave such regions a more wooded look.

Agricultural productivity was maximized by crop rotation, which in champion regions generally involved what is known today as the

three-field

system. By the early Middle Ages, it had been recognized that constant farming of land exhausts its ability to produce crops. However, certain kinds of crops helped refortify the land for producing wheat. In the three-field system, the village fields were divided into three large zones. In October–November, one of these three fields would be sown with a winter crop of rye and wheat (called a winter crop because it was planted in the winter). The second field would be sown the following spring with a spring crop of barley, oats or legumes (such as peas or beans). The remaining third would lie fallow, or unused, and would be plowed and fertilized during the spring and summer to help restore its strength. While the ground was lying inactive, villagers were allowed to pasture their animals there, feeding on the plants that naturally grew, and fertilizing the soil with their manure. All the crops were harvested in August and September, after which the fields were rotated: the fallow field would be planted with winter crops, the winter field would be planted in the spring, and the spring field would lie fallow.