Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (34 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

As soon as a young girl had reached puberty, she donned the

veil and no man could see her face and body unless it was her father, immediate

male kin, and, later, her husband. She even covered her hands with gloves. To

preserve her privacy and veiled status, the windows of the women’s apartment

opened to an inner courtyard. If there were any windows facing the street, they

were barred so tightly that no outsider could see the inside of the room.

In the first half of the 18th century, ladies of the court

and women of upper classes wore a pair of very full pants that reached their

shoes and concealed their legs. These pants came in a variety of bright colors

and were brocaded with silver flowers. Over this hung their smock with wide

sleeves hanging half way down the arm and closed at the neck with a diamond

button. The smock was made of fine silk edged with embroidery. The wealthy

women wore a relatively tight waistcoat with very long sleeves falling back and

fringed with deep gold fringe and diamond or pearl buttons. Over this they wore

a caftan or a robe, exactly fitted to the shape of the body, reaching the feet “with

very long straight-falling sleeves and usually made of the same stuff as the

pants.” Over the robe was the girdle, which for the rich was made of diamonds

or other precious stones, and for others was of exquisite embroidery on satin.

Regardless of the material it was made of, the girdle had to be fastened “with

a clasp of diamonds.” Over the caftan and girdle, women wore a loose robe

called

cebe,

made of rich brocade and lined either with ermine or sable,

was put on according to the weather. The headdress for women from wealthy

families “composed of a cap called

kalpak,”

which in winter was of “fine

velvet embroidered with pearls or diamonds and in summer of a light shining

silver stuff.” The cap was “fixed on one side of the head hanging a little way

down with a gold tassel, and bound on either with a circle of diamonds or a

rich embroidered handkerchief.” On “the other side of the head,” the hair was

laid “flat and here the ladies” were “at liberty to show their fancies, some

putting flowers, others a plume of heron’s feathers,” but “the most general

fashion” was “a large bouquet of jewels made like natural flowers; that is, the

buds of pearl, the roses of different coloured rubies, the jessamines of

diamonds, the jonquils of topazes, etc, so well set and enamelled ’tis hard to

imagine anything of that kind so beautiful.” Finally for their footwear, women

wore “white kid leather embroidered with gold.”

Women did not leave their homes before sunrise or after

sunset, except during the holy month of

Ramazan,

and even then, ladies

from wealthy families did not appear on the street unless they were accompanied

and attended by several servants, who walked at some distance behind them.

Segregation between the sexes was observed at all times. Men did not walk on

the street next to their wives or mothers, and inside the house women had their

meals apart from the men. Even among poor families, a curtain separated the

men’s quarters from the women’s. On everything from steamers and ferries to

streetcars, which were introduced in the 19th century, curtains designated

separate compartments for women. Until the second half of the 19th century,

even Christian churches observed and respected the segregation of sexes in a

house of worship.

Piety was the hallmark of a woman’s life. Muslim women

prayed five times a day and fasted during the month of

Ramazan.

On

Fridays, many attended prayers at a mosque where they had their own section,

separate from men, and, during

Ramazan,

those living in Istanbul went en

masse to evening service at the majestic

Şehzade

mosque. Many women

of power and prominence had their own personal prayer leaders (imams) and

spiritual guides.

Going to a bathhouse was another important occasion for the

women of the household. Once a week for at least four to five hours, the women

of rich and powerful families set out for a nearby bathhouse, followed by a

retinue of servants carrying on their heads bathing robes and towels, as well

as baskets full of fruit, pastry, and perfumes their mistress was to consume

during her long visit away from her home. Once inside the bathhouse, women

relaxed, took off their clothes, drank coffee or sherbet, shared the latest scandal

or gossip, and lay down on cushions as their slaves braided their hair. With

the introduction of private baths, public hammams lost their popularity, but

they never disappeared completely.

Before the arrival of capitalism and modern factories in

the 19th century, a woman living in a village or a tribe played a far more

important role in the economic life of her community than a wealthy woman

living in a city. From working on the land and caring for animals, to spinning

wool and cotton, and producing rugs and carpets, the economic function and the

social role of a village woman was critical to the survival of her family and

community. She was also responsible, by custom and tradition, for keeping the

house tidy, preparing meals, and taking care of children.

In sharp contrast, the rich urban woman was far less

critical to the economic life and survival of her husband and family. Among the

rich, cooks prepared the meals, while nurses, nannies, and tutors took care of

the children and their daily basic needs. This level of support provided

wealthy women with ample time to enjoy themselves by going to parks for

picnics, inviting female friends and relatives for coffee and sweets, and

entertaining their guests with dancers and musicians. In the second half of the

19th century, a new middle class educated in European languages and Western

ideas emerged. Women from these middle-class families began to attend schools

where they studied foreign languages, European history, modern ideas, and

philosophies. It was from the ranks of this new class of educated women that a

new generation of female business leaders, parliamentarians, and scholars

emerged.

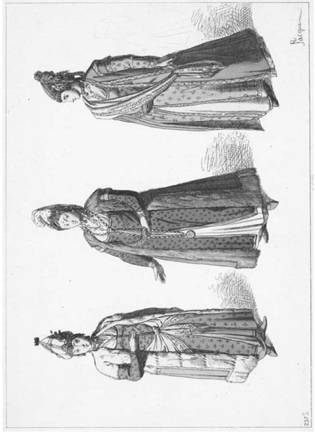

Ottoman women in the traditional

clothes. Dames Turques (1863–1869).

A woman of Istanbul (1667).

DIVORCE

Divorces were prevalent in Ottoman society, and men could

divorce their wives without any explanation or justification. In numerous

instances, women also filed for divorce. There were three types of divorce. The

first was

talaq,

which allowed a man to “divorce his wife unilaterally

and without going to court simply by pronouncing a formula of divorce.” The

Muslim women in the Ottoman Empire could not use

talaq

to divorce their

husband, but they had the right “to obtain a court-ordered divorce (

tafriq

).”

A “woman could also negotiate a divorce known as

khul

with her husband

by agreeing to forego payment of balance of her dower or by absolving him of

other financial responsibilities.” Affluent women seeking divorce paid an

additional sum of money to secure their husband’s consent to divorce. Unless “the

khul

divorce specified otherwise, a woman gained certain entitlements

upon divorce.” She could “receive any balance owed on her dower, and material

support for three months following the divorce.” Payment of alimony was “decided

by the court on the woman’s application, not only in cases of formal divorce

but also in instances of abandonment or if the husband failed to provide for

his family.” Additionally, “any underage children born of the marriage were

entitled to full financial support from their father.” At the time of divorce,

it was unlawful for husbands to take from their wives anything they had given

them, including gifts before marriage and during the wedding ceremony.

The wife was entitled to divorce her husband and seek

another man if she was not satisfied with the house to which her husband had

taken her. She could also file for divorce if the marriage remained

unconsummated, if the husband was impotent or mentally unstable, or if he had

committed sodomy or intended intercourse in ways that were viewed as abnormal,

or if he had forced her to drink wine against her wishes. Other legitimate

causes for divorce were “incompatibility, ill treatment, including physical

abuse by the husband, financial problems that led to altercations between

spouses, adultery, failure of one or both parties to keep to the basic

expectations of marriage, especially not doing the work the family needed from

either husband or wife,” and the inability of the wife to produce sons who “were

greatly desired and needed for financial security, to carry on the family and

support the old folks.” Women were often blamed for not producing sons, and

divorce “caused by a lack of sons was not uncommon.” A man without a son was

justified by custom and tradition to marry another wife who would produce a son

for him.

Though divorces were common in the Ottoman Empire, there

were many factors that worked against them. Because marriages were arranged

between families and not individuals, divorces would not only impact the

husband and the wife but two large and extended families, which had established

personal, familial, and at times, social and financial ties. Both families had

invested a great deal, both in expenses and goods, not to mention time and

emotions. Poor and struggling families, who had spent a great deal to purchase

household goods and build a house, could not afford losing their investment.

Outside financial concerns, the impact on children and “public shame” were also

important factors in preventing divorces. If “a man or a woman caused a

marriage to dissolve for what fellow villagers thought was a bad reason, the

entire village would censure him or her, and public shame was not easy to live

with in a closed society.”

After divorce, both men and women were free to marry again.

In the Quran, divorced women were commanded to wait “three menstrual courses”

before they could marry again. Very few divorced individuals remained

unmarried, and though women were required to wait 100 days before remarrying,

this rule “was routinely broken” and remarriage came shortly after divorce. If

a man divorced his wife, he could not remarry her until she had wedded another

man and been divorced by him. In case of a second marriage between the same

individuals, the husband was obligated to promise the payment of

mehr.

11 - EATING, DRINKING, SMOKING,

AND CELEBRATING

Preparing,

serving, and eating food was of the utmost importance to the social life of

every urban and rural community in the Ottoman Empire. Around “this basic

element of life revolved numerous rituals of socialization, leisure and

politics.” Consuming food “in this world was most closely associated with the

family and home, for there was no such thing as a culture of restaurants and

dining out was rare.” When a person ate outside his/her home, “it was usually

in the home of a friend or family member.”

Ottoman cuisine synthesized a wealth of cooking traditions.

The ancestor of the Turks who “migrated from the Altay mountains in Central

Asia towards Anatolia encountered different culinary traditions and assimilated

many of their features into their own cuisine.” As they conquered and settled

in Asia Minor and the Balkans, they left a marked impact on the cuisine of the

peoples and societies they conquered. Their own daily diet, in turn, was

greatly influenced by the culinary traditions of the peoples they came to rule,

such as the Greeks, Armenians, Arabs, and Kurds. Indeed, the wide and diverse

variety of Ottoman cuisine can be traced back “to the extraordinary melting pot

of nationalities that peopled the Ottoman Empire.”